The sailor’s grave is a battleship called the USS Arizona.

Joseph John Borovich died on that famous U.S. Navy vessel 63 years

ago Tuesday.

The sailor’s grave is a battleship called the USS Arizona. Joseph John Borovich died on that famous U.S. Navy vessel 63 years ago Tuesday.

He was only 21 years old on that Sunday morning history will never let Americans forget. Dec. 7, 1941, President Roosevelt told a shocked nation, is “a date which will live in infamy.”

Growing up in Hollister, I often heard people talk about “Joe” Borovich. Even though he died a quarter century before my birth, I feel I’ve come to know him a bit from listening to the stories of his friends and family.

Sometimes, as a teenager, I’d stop by the San Benito County History Museum and chat with Lucy Borovich, the curator, about her memories of her brother. And his sister-in-law, Mary Borovich, was a good friend of my family. She told me about the day Joe participated in her wedding to his brother Pete Borovich.

“There’s so many memories, you know,” Mary said softly. “What a wonderful young man he was – and how everyone just took to him.”

Joe was born on New Year’s Eve 1919 – a year after the world supposedly ended “a war to end all wars.” Of Yugoslavian ancestry, he grew up on a farm in the San Juan Valley.

His sister Pauline Borovich remembered an incident when Joe was five years old.

One day, the family’s small dog bit the boy. Immediately, Joe sunk his own teeth back into the pet. “Now how do you like that?” Joe had demanded to know.

Pauline smiled at the recollection of long ago. “I always think of him with that statement of his,” she said. “He was the baby of the family. ‘Baby Joe’ we called him.”

The young Borovich boy went to Sacred Heart School in Hollister during his early grades, followed by four years at Serra High School (now gone) in the town. Joe was no brilliant scholar – more of an “average student.”

Like most American kids, Joe enjoyed sports.

He played tight-end on the football team.

And at a towering 6 feet, 6 inches (with a shoe size of 13EE!), the teenager was always a sure pick for the basketball team – a game he loved.

He also loved people, Pauline remembers. He had a couple of romances in his life.

A pretty Hollister teenage girl awoke something in his heart in high school. Later, a beautiful young woman in San Francisco caught his attention.

And the likable lad had another love – for adventure. “He wanted to join the Navy, that was his great desire,” Pauline said.

Perhaps life in a sleepy California farmtown during the 1930s made Joe dream of roaming the great wide world. His imagination must have took him on voyages across vast seas to exotic ports – a wanderlust wish shared by farm boys in dull towns across America.

While dreaming that dream, the hardworking teenager labored as a farmhand on Winnie Freitas’s pear orchard in the San Juan Valley.

“He drove a tractor, irrigated, pruned – you name it, he did it,” his brother George Borovich recalls.

One time while spraying the pear trees, Joe accidentally got a mist of pesticide in his face, damaging his eyes. He wasn’t blind, but it blurred his vision, causing the Navy to reject his enlistment application.

He wouldn’t let the Navy’s “no” discourage his ambitions.

Whenever he drove a truckload of pears up to San Jose, he always stopped at the Navy recruiting depot at the Moffett Field Airbase to undergo the military’s rigorous testing. He never did pass the eye-chart examination.

“I know he pestered them awful hard,” George spoke of Joe’s determination. “He wouldn’t give up.”

One day, after failing yet another eye exam, the 19-year-old started ambling dejectedly down the Navy hall.

A firm hand reached out and grabbed his shoulder. “‘Borovich!” exclaimed a stern voice.

Surprised, Joe turned.

“Any man who wants to get into the Navy as badly as you do will get right in!” the recruiting officer told him.

Overcoming the obstacle of eye-charts, the young man’s aspirations for adventures finally became real.

That adventure took him across Pacific waters to the American territory of Hawaii. His floating home was the USS Arizona.

He proudly served as a seaman first class.

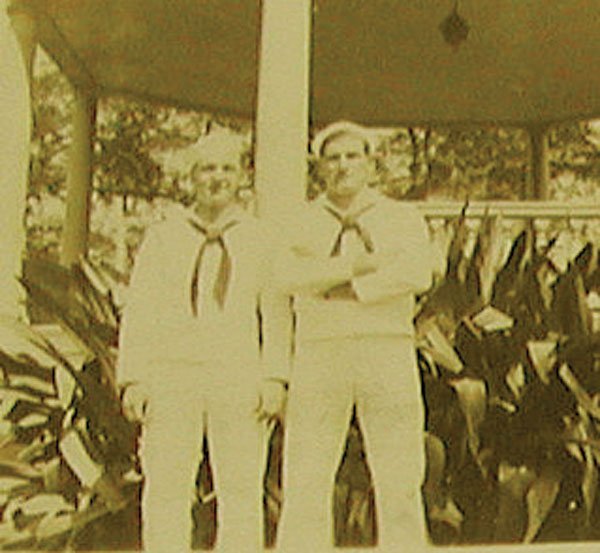

Look at a photograph of Joe in his white sailor uniform, and you’ll see him standing awkwardly a head above his crew mates. He beams under his sailor hat. In the Navy, he had the time of his young life.

On a quiet Sunday morning, Joe Borovich found himself under the Arizona’s decks getting ready for a beach picnic with friends.

Holiday lights decked palm trees along Honolulu’s streets. Bing Crosby warbled on the radio. And 350 Japanese warplanes flew over ocean waves toward an unprepared U.S. military base called Pearl Harbor.

Shortly before 7:55am, the first wave of fighters buzzed target areas.

Their hail of bullets cascaded down on surprised servicemen below.

Bombs plummeted the line of vessels moored along “Battleship Row.” Panic and confusion broke out.

About 8:10am, a 1,760-pound armor-piercing projectile dropped from a Japanese high-altitude bomber.

It impacted the Arizona’s gun turret No. 2, then slammed through decks. The battleship’s forward ammunition magazine instantly exploded.

Orange flames and black smoke roiled from twisted metal of the burning superstructure. Men screamed, trapped inside the hell of wreckage. Water flooded compartments.

In less than nine minutes, the Arizona sank. It suffered a loss of 1,177 American sailors and marines. Joe’s body was never found. Like the rest of the nation, the Borovich family back in Hollister felt tremendous shock.

“My mother was heartbroken,” Pauline said. “I’d say that was the cause of her death. A short time after that she died.”

The loss still affects Joe’s surviving siblings and friends.

George stared into the past. “He was straight as a nail,” he recalls of his brother fondly.

Pauline once visited the Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor. There, she had read Joe’s name on the list of casualties. She had peered down through the lapping waves at Joe’s grave.

“All I could see was the turret coming out of the water – and the oil coming out,” she remembered. “A few tears were shed. I said a prayer for him.”

Near Veteran’s Memorial Park in Hollister, a suburban street-sign now bears the name “Joe Borovich Drive.”

It honors the Hollister farmhand who wouldn’t let anything stop him from joining the Navy.

Today, we remember this date as the anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack. Nineteen ships were severely damaged or destroyed.

The lives of 2,403 Americans were lost. Pearl Harbor forced America into a global war which led to our nation becoming a world superpower.

That Sunday morning in Hawaii, as he prepared for a picnic outing with sailor buddies, Joe Borovich died on “a date which will live in infamy.”

But the Navy man will forever live on in the heartfelt memories of the people who knew and loved him.