Early Hawaiians believed Pele forced her disciples to quake with

fear when she became angry or displeased. Among Native Americans of

the Pacific Northwest, stories said the Thunderbird fought the

great whale of the deep and, in his move of victory, dropped this

beast of the sea onto land with a great shudder.

Early Hawaiians believed Pele forced her disciples to quake with fear when she became angry or displeased. Among Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest, stories said the Thunderbird fought the great whale of the deep and, in his move of victory, dropped this beast of the sea onto land with a great shudder.

Among the writers of the Bible, earthquakes struck in times of great moral darkness – at Sodom and Gomorra, in the temple of Delilah and at the crucifixion’s completion.

Forces of nature too large to comprehend have intrigued man for centuries – from fires that can consume the natural wonders of four states simultaneously to tornados capable of flattening homes while leaving a single, frail stalk of wheat untouched in the same path. In the attempt to explain the phenomenon of earthquakes, thousands of theories have emerged. Clouds, animals, dowsers, electrical readings as well as moon cycles and psychic visions are all supposed methods of divination, and hundreds of people claim to predict earthquakes.

All of these methods have come under fire from the scientific community, but in China, where an earthquake can mean the loss of thousands of lives, the government has been more willing to look into the possibility that the signs may be there. In the winter of 1975, scientists in that country began to notice a confluence of bizarre readings. Near the town of Haicheng, land elevation and water levels were changing. Animals were acting strangely and a the small earthquakes the area had been experiencing were becoming more frequent. On advice from researchers, the city was evacuated.

The move saved an estimated 150,000 people. Haicheng was all but decimated by a magnitude 7.3 quake just a few days later, killing 2,041 people.

The scientific community celebrated the prediction’s success, but their joviality was short-lived. On July 28, 1976 an even larger quake, magnitude 7.6, struck the city of Tangshen, killing more than 250,000 people. There had been no warning – no foreshocks, no noticeably spooked animals … nothing but utter devastation.

“We have come a long way since I started in the field,” said Ruth Ludwin, a research scientist for the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network at the University of Washington. “We know where the faults are and even which faults are more likely to produce large quakes. There’s an alarm system. If there are a certain number of quakes over a high enough magnitude we can be fairly sure that a bigger one is coming. What we haven’t been able to do is to say, ‘it’s coming on this day at this time.'”

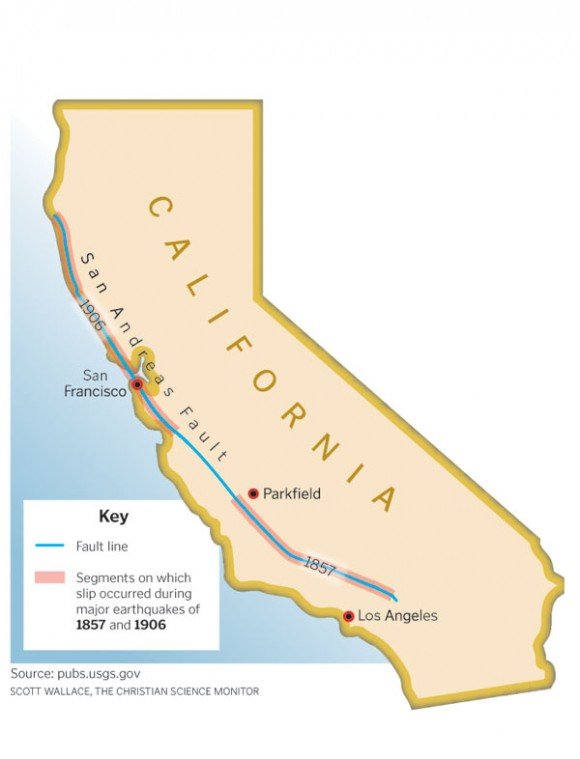

The idea of an earthquake – slipping between the plates that make up the earth’s surface – is well understood, but what precipitates a large occurrence versus a smaller one remains a mystery. Stress levels build over time on faults. A series of small earthquakes can release some of this stress, or it may violently work its way out in one large temblor. Scientists, for instance, were aware that the section of the San Andreas fault that produced a 6.0 in Parkfield, Calif. last month was due for some relief.

“It was originally scheduled to go quite a few years ago,” said Ludwin. “The original window was between 1988 and 1992, so I do have trouble viewing that as an unqualified success in terms of prediction.”

This skepticism marks the scientific community, which is wary of almost all predictions. Instead they prefer the term “forecasting.” Forecasts cover periods of time spanning decades, like the United States Geological Survey’s forecast of a 6.4 or larger quake in the San Francisco area by 2030. Predictions, on the other hand, are limited to far more narrow parameters – months or even days.

The prospect of predicting quakes may seem dim, but plenty of scientists are willing to try. Geologist Rand Schaal of the University of California, Davis, studied the correlation between the number of missing cats and dogs in the San Jose area and the occurrence of earthquakes in the same time period. He found that no conclusive evidence could be drawn. Geophysicist Dr. C. Thanassoulas of the Institute of Geology and Mineral Exploration in Athens, Greece, is monitoring ground-based electrical currents in an effort to predict the location of that country’s next big quake.

Earthquake researcher Zhonghao Shou believes that he can narrow earthquake predictions down to a matter of days – around 35.

After reading about the ancient Chinese and Italian beliefs in earthquake clouds, Shou decided to study them himself.

He studies satellite images, looking for dark, snakelike clouds in otherwise clear skies to predict temblors. Based in New York, Shou, who published his study, “Earthquake Clouds: A reliable precursor” in the Turkish journal Science and Utopya, claims to have a high success rate.

Cloud-cover may seem a more dubious method of earthquake prediction, but NASA is also looking to satellite technology as a way to predict where large quakes will strike.

NASA geophysicist Carol Raymond works on the Global Earthquake Satellite System. With interferometric synthetic aperture radar – radar that can detect minute deformities in the earth’s crust – her team is looking to decipher how and where the earth’s crust is moving.

“It is important to understand that better earthquake forecasting can be used to prioritize retrofitting projects and to better prepare the general public,” Raymond said in a July interview with National Geographic. “But it is unrealistic to envision earthquake prediction resulting in planned evacuations of cities or towns.”

Some serious scientists think predictions aren’t out of the question, but that their development will take time.

UCLA seismologist and mathematical geophysicist Vladimir Keilis-Borok, who has worked on an algorithm to predict quakes for 20 years, made an attempt at what he called the “Holy Grail of earthquake science” last January. He announced publicly that an earthquake of magnitude 6.0 or greater would strike the Southern California region by September. None of such magnitude had been recorded; the Parkfield quake was too far north to be included in his prediction.

“I think there’s a possibility that we’ll be able to predict earthquakes at some point in the future,” said John Vidale, a geophysicist at UCLA who works with Keilis-Borok. “Maybe it’ll be a process where we’ll never know the exact day, but we’ll be able to tell people to be prepared.”

The tragedy of Tangshen may have crushed the hope of easily predicting earthquakes, but the hope of seismologists has since become more practical.

“Think of a fault as a little disk balancing on a pencil,” said Ludwin. “If you drop one grain of sand at a time onto the disk, you’ll eventually get a little pile and that pile will become more and more unstable as you continue dropping on grains. You don’t know which grain will cause a slide or how large it will be, only that one will. At some point, if you understand all the grains of sand, you might be able to predict it.

“Our goal now is to have major infrastructure that can withstand what we think is coming, so you can get back to business and have a place to work. We want to avert a disaster by being ready, so that at the end of the day you can know that you have a home to go back to.”