When we flip through maps looking for destinations with scenic beauty and solitude, we generally find places with proper names and boundary lines that define them. Yosemite National Park, Henry W. Coe State Park, Rancho Cañada del Oro Open Space Preserve and the John Muir Wilderness are all distinct regions carefully defined on a map.

But in the vast expanse of the American west, there are still amazing places with no entry gate, no lodges and no gift shops. It might take some extra effort and some of the comforts are missing, but without the proper name to draw attention, these places offer a special opportunity for isolation and discovery.

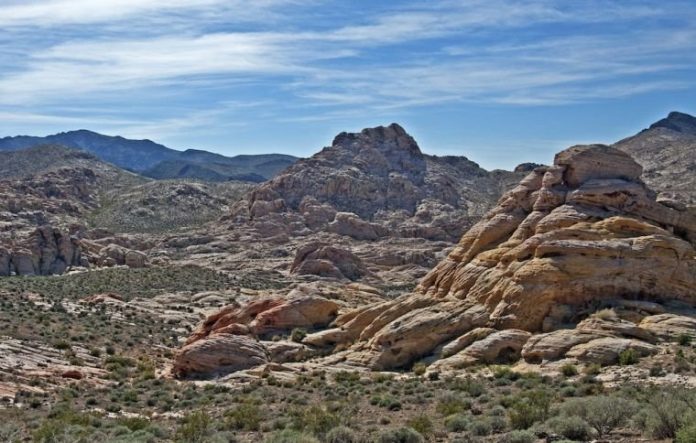

Awhile ago, while flipping through a coffee table book with photos of the Great Basin, I was struck by a shot of the Muddy Mountains. It was one of those magical scenes, stunning in the soft morning light, where a rambling expanse of rounded rock formations in countless shades of pink, orange, red and white pop out of the immense drab brown desert. I ran to my maps.

The Muddy Mountains don’t reside within a national park or some other carefully controlled preserve, so finding them on a map was a challenge. They are just another in the succession of mountain ranges in the Basin and Range region that reaches across Nevada. There they are!—not too far off of Interstate 15 a short drive east of Las Vegas – a perfect side trip on my springtime journey to Zion National Park.

About a half hour drive east of Las Vegas, I turned right onto Valley of Fire Highway. At the end of a long straight stretch, the highway veered east, but I continued straight ahead onto the Bitter Springs Trail (aren’t desert names great!), a dirt road that leads into the heart of the Muddy Mountains. It was easy going until the road began to twist along an arroyo that cut through the first fold of the range. My Subaru has enough clearance to handle some road obstructions, but the going was getting awfully rough. It appeared that the terrain opened up a short distance ahead, but I decided to leave the car and proceed on foot. Sure enough, a half mile ahead the landscaped widened and a brilliant rolling desert playground spread out before me.

Here was a wanderer’s paradise. No trails, yet the terrain was easily accessible and every direction beckoned. I headed for high ground to get the lay of the land. I scampered over rock outcrops that were a beautiful weave of thin colored layers laid down in some aquatic environment eons ago. Everywhere, tipped layer cakes of sediments would adjoin a counter tipped group of sediments, the direction of the sediments abruptly zigging and zagging up and down the outcrop before me. There is never a geologist around when you need one, but my ignorance of the science didn’t hamper my appreciation of the beauty.

From up high, I could see sections of brightly colored rock protruding from the gray alluvial deposits on the flanks of higher peaks to the south. It seemed that another million years of erosion would reveal the underlying rock and tie these sections in to an unbroken expanse of red.

Which way next? It didn’t matter. Everywhere I wandered the show was grand; polished hollows carved in the rock by wind and water, narrowly balanced rock thumbs statues standing solitary and tall, even elegant traceries of wind-blown grass blades in the sand.

Not all of the scenic west is tagged and tamed. Some of it still runs wild.