Every square inch of Frank LaCorte’s office tells a story. A

framed California Angels baseball jersey hanging behind his desk

recounts his 10-year Major League career.

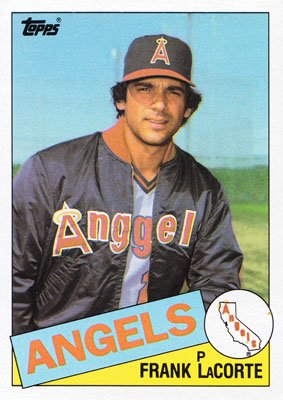

Every square inch of Frank LaCorte’s office tells a story. A framed California Angels baseball jersey hanging behind his desk recounts his 10-year Major League career.

The head of an African cape buffalo affixed high on his wall retells a thrilling and frightening hunting excursion. Even the minibar in the corner provides insight. Jack Daniel’s Tennessee Whiskey and Sierra Nevada Pale Ale tell of LaCorte’s dependable, though hardly boring, taste.

Resting in the middle of the room, however, is the biggest storyteller of all. It’s LaCorte, and he’s got plenty of material.

From 1974 through 1984, the Gilroy-born LaCorte survived a players strike, arm ailments and some of baseball’s most feared hitters to get those stories. To call him just a baseball player would be an insult to his love of hunting, and to say he’s just a hunter would be an insult to his rotator cuff. To say he spends all his time golfing would be an insult to his business, Marx Towing.

But he stared down a mammoth Dave Winfield – while giving up half a foot in height – and proudly lived to tell of it. It’s no wonder LaCorte’s gab has so much to do with the game.

“Baseball is a big part of my life.” he said. “It’s always been in my life.”

It was prunes, not baseballs, that LaCorte threw first. Growing up in a family of prune farmers, LaCorte would often take time during picking season to chuck a few around. It’s never been determined whether that was the secret to his sometimes-dazzling knuckle curve.

LaCorte was never drafted. He missed two years on the mound in high school due to arm problems and later had a screw surgically implanted in his pitching elbow. After playing at Gavilan College for two years beginning in 1970, LaCorte competed in the National Baseball Congress World Series, a tournament that then pitted the winners of semipro baseball leagues from around the United States, in Wichita, Kan.

When the tournament ended, the Braves liked what they saw and signed him after a 20-minute workout. After four up-and-down seasons in Atlanta, LaCorte was traded in May of 1979 to Houston. The 1980 season would be LaCorte’s best, and arguably one of Houston’s best as a franchise. LaCorte set career highs in wins, earned run average, games pitched and saves. The Astros also came within one win of a World Series appearance, losing a heartbreaking National League Championship Series to the eventual world champion Philadelphia Phillies.

“We were the better team,” LaCorte maintains.

The next year, LaCorte caught a glimpse of what life without baseball would be like. On May 29, 1981, the players union board of directors voted unanimously to go on strike. The strike lasted 44 days. On day one, LaCorte closed escrow on his home.

“Forty-four days of no paycheck,” he recalled. “It was terrible. It was almost like starting over again.”

Despite his love for the game, LaCorte won’t often be spotted at a Major League stadium. Today, the salaries are too high, the pants too baggy, the jewelry too flashy and the tattoos too prevalent. And watching from the stands just can’t compare with lacing up his spikes and digging them into a mound of dirt. It can’t even compare with running laps in the outfield.

“When you play and you’re on the field, and you’re in the ballpark and competing – that’s your sport,” he said. “But I don’t go to games and sit there and watch. I just don’t do well with that.”

On Oct. 28, 2010, LaCorte did his best. He didn’t turn down free tickets to watch the Giants face the Texas Rangers at AT&T Park for Game 2 of the World Series. An obvious and robust supporter of pitchers, LaCorte wasn’t disappointed with Giants pitcher Matt Cain’s complete-game, 9-0 shutout win.

LaCorte stayed until the final pitch, though it wasn’t the game’s conclusion that had the biggest effect on him. It was standing alongside 43,622 other spectators as four jets soared overheard during the National Anthem.

“That brought tears to my eyes,” he said.

He never played for the Giants, but LaCorte still had ties to the world champs. For the 1979 and 1980 seasons, LaCorte roomed with current Giants manager Bruce Bochy when the two were teammates in Houston.

LaCorte said he saw traits of a lot of his old Astros teammates in the most recent world champs.

“We were just a bunch of young guys. We didn’t know any better,” LaCorte said. “We were like the Giants last year. All pitching, some hitting – timely hitting.”

If a city had a ballpark, LaCorte likely visited it. He said it was difficult to pin down one city or stadium that was his favorite to visit. He loved the

baseball-centric downtowns of Cincinnati and St. Louis. The Hollywood-manicured playing surface and mile-high mound at Dodger Stadium were heaven on earth for a pitcher, he said.

Even Wrigley Field in Chicago had its moments.

“The fans are always right there, spilling beer on you,” LaCorte laughed.

There wasn’t much to laugh about during LaCorte’s final big league season, however. He appeared in just 13 games for the Angels in his first year of a

brand-new, three-year contract. He wouldn’t play in another one.

When doctors examined his rotator cuff, “They said it was one of the worst ones they’ve ever seen,” LaCorte said.

He underwent rehabilitation, but didn’t feel as though his arm was getting any healthier. He decided to retire.

“One day, I thought my whole arm was going to come out of the socket,” LaCorte said.

LaCorte’s arm stayed attached. That allowed him to focus on another passion, one that actually predated his pitching days – hunting.

“I’ve done that since I was a little kid,” he said.

In his office at Marx Towing – a “recession-proof” business he purchased in 1994 – LaCorte’s walls are overwhelmed by the heads of deer, wild pig, cape buffalo and dozens of other animals from three continents. A red stag from Argentina is one of his most prized victories.

“I look at my animals and think I got a story,” he said.

And it’s deer, easily, that give him the most trouble.

“Deer hunting is the hardest,” LaCorte said. “A mule deer is the hardest to get.”

LaCorte said he and his hunting partners are a lot like a baseball team. Only each time, they play with the same lineup.

“I don’t hunt with different people,” he said sternly.

The same goes for his business.

“I feel like I’m a manager trying to put together a good team,” LaCorte said.

LaCorte, who will get a new knee and turn 60 this year, has been married to his wife, Karen, for 36 years. Their son, Vince, is 32 and daughter, Vanessa, is 27.

His friends help him keep a leg or two in the limelight, though. He’ll golf with Reggie Jackson and play cards with Rod Carew.

As the years move on, however, the Hall of Famers will have to start coming LaCorte’s way. He has no plans of moving.

“No. We have too many friends and family here,” LaCorte said. “I live for my friends.”