With one hand rummaging through a bag of chips, the other

grabbing a computer mouse and both ears plugged into an iPod,

sophomore Nathan Kassel is not the typical picture of learning. Yet

he and scores of high school students have spent dozens of

afternoons glued to a computer, not playing video games, but in

pursuit of academics.

Gilroy – With one hand rummaging through a bag of chips, the other grabbing a computer mouse and both ears plugged into an iPod, sophomore Nathan Kassel is not the typical picture of learning. Yet he and scores of high school students have spent dozens of afternoons glued to a computer, not playing video games, but in pursuit of academics.

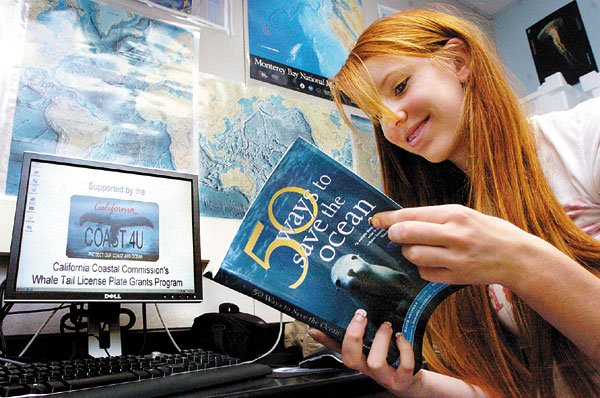

Kassel, a 16-year-old marine biology student at Gilroy High School, put the finishing touches last week on a short film he and his partner, 16-year-old Branden Jimenez, spent more than a month researching, filming and editing. Their documentary on over-fishing will be shown as part of the first Neptune’s Guardian Film Festival tonight at 7pm in the student center.

“A bunch of my friends are in marine science so we’re going to head over there,” 17-year-old junior Matt Stuck said. “It’s going to feel cool.”

This year’s students are the first to have a video-making component included in their marine-science course. The equipment and programs needed to make the documentaries were provided by a $14,000 grant authored by high school science teacher Jeff Manker in March.

His hope was that the technology would engage the 300 students in the 10 sections of marine science. Students first studied the nine dangers to oceanic health identified by the Pew Ocean Commission and produced a report on one of them. Then, instead of making a poster or a PowerPoint presentation – as done in the past – Manker required his class to create films.

“It’s the difference between 2-D and 3-D,” he said. “To me, the PowerPoint is a very flat sort of thing – you put a picture to show what I’m doing. But a movie explains and … to explain something, you really have to know it.”

Students agree the project increased their knowledge about oceans.

“The video helps a lot,” Kassel said of learning about over-fishing. “It’s a lot bigger problem than we thought. I didn’t know it affected more than just the ocean. Now we know it.”

In addition, films are better means for dispersing knowledge than papers, Stuck said.

“It makes it so you get more into it,” he said. “You can interact more, you can see pictures of it.”

Despite the enthusiasm Manker’s class showed for the project, only about a third of students took part. Few teachers had experience with the equipment or programs used to edit the movies and therefore made the documentaries optional. Manker expected that the first year might not get high participation, but has high hopes for the film project in the future.

“I hope it becomes something that kids fight to get into this class to be able to do,” he said.

The goal is ultimately to convince students their knowledge will be recognized if they voice it well, Manker said. With films already receiving nearly 100 views on video-sharing Web sites, such as YouTube, the lesson is not lost.

The festival is another platform for students to express themselves, educate their peers and value knowledge, Manker said.

“The idea was not just to make them make a video, but to get them attention for

making a video,” he said. “The film festival – it’s an important component. It makes them realize what they think and do matters.”