A battle for God, church and booty

They were savage and barbaric, with a special fondness for

beheadings. Their spiritual leader assured them they were doing

God’s work and that if they died in battle, they’d go straight to

heaven.

A battle for God, church and booty

They were savage and barbaric, with a special fondness for beheadings. Their spiritual leader assured them they were doing God’s work and that if they died in battle, they’d go straight to heaven.

These weren’t modern-day terrorists, but 11th-century Christian crusaders. At the behest of Pope Urban II, eager to shore up his position as the head of the church, they set out in 1095 to retake the holy city of Jerusalem. Urban’s fictitious tales of Muslim atrocities – pure propaganda – had sent an electric shock through Europe. Some 100,000 people – knights, clergy, and peasants – began an armed pilgrimage, the biggest mobilization of manpower since the fall of the Roman Empire. It was a response that astounded Urban himself.

The four-year campaign fulfilled secular and spiritual ambitions, according to Thomas Asbridge, the author of this rousing history titled “The First Crusade.” As both savage brutes and devout Christians, they attempted “a new form of ‘super’ penance: a venture so arduous, so utterly terrifying, as to be capable of canceling out any sin,” he writes. Their violence was done in the name of God, using a radical interpretation of St. Augustine’s “Just War” theory. (One apologist pointed out that Jesus had asked Peter only to put away his sword, not discard it, at the Garden of Gethsemane, obviously meaning that he would be called on to wield it in the future.)

Asbridge knows this territory well. In 1999, he even walked 350 miles of the crusaders’ route. But he warns us not to read contemporary views of morality into this era. “In the minds of the crusaders, religious fervor, barbaric warfare, and a self-serving desire for material gain were not mutually exclusive experiences,” he says, “but could all exist, entwined, in the same time and space.” After the fall of Jerusalem on July 15, 1099, the knights went directly to worship at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher – the accepted site of the Crucifixion – bathed in their enemies’ blood and carrying their booty with them.

Eventually, their reputation for “absolute ruthlessness” – at one point, nearing starvation, they resorted to cannibalism – helped them: Entire Muslim cities surrendered rather than face brutal annihilation.

Despite being drawn from many countries and speaking many languages, the crusaders slowly became a cohesive army under a council of princes. On the whole, the system worked well, though the leaders perpetually squabbled over power and wealth. (It also helped that they faced a series of fractious Muslim rulers.)

The pivotal battle, a prolonged siege of the great city of Antioch, tested the crusaders to the breaking point. A traitor finally let a band of them climb over a wall, and Antioch quickly fell, but just as a Muslim army was arriving to relieve the city. The besiegers suddenly became the besieged.

At this point, historians usually give great importance to the crusaders “finding” a powerful relic, the Holy Lance of Antioch, alleged to be a Roman spear with Jesus’ blood on it. This gave them courage – some accounts say actual miraculous help – to rush out of the city and defeat a vastly superior force. More likely, Asbridge says, the crusaders simply recognized their hopeless position and, after failing to negotiate a withdrawal, decided that a bold attack was their only chance of survival.

Although all the conquered land eventually fell back into Muslim hands, the First Crusade was a seminal event, Asbridge says. It “set these two world religions on a course toward deep-seated animosity and enduring enmity,” he notes, the “chilling reverberations” of which “still echo in the world today.”

By Gregory M. Lamb

The Christian Science Monitor

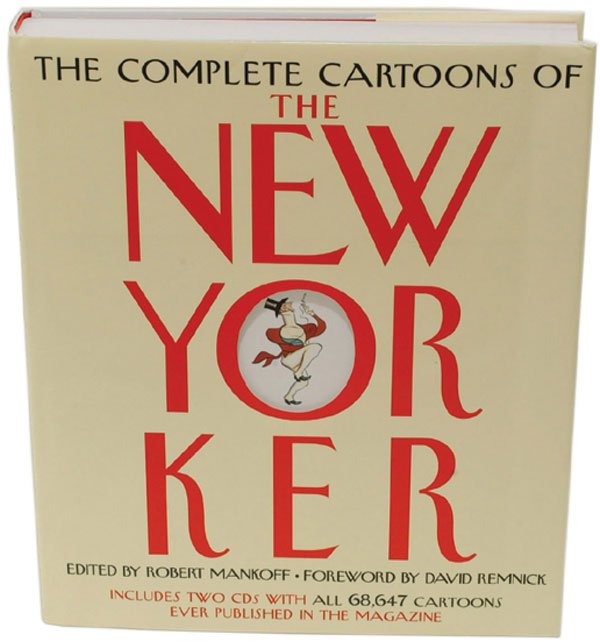

The New Yorker’s inscrutable, evolving humor

Shore up your living room coffee table: Here comes the heaviest book in the house. With a $60 price, it weighs in at 9 pounds, and there’s more. The book itself contains only 2,000 cartoons, with commentary by various New Yorker writers, but also included are two CDs with all 68,647 cartoons ever published in the magazine.

Whether this is a worthy project and a cause for celebration depends on your ability to sit for hours in front of the computer – and whether you need another reason to do so. But scrolling through the decades, you do notice something about the development of a magazine that has defined a good chunk of the American sense of humor.

The New Yorker began in 1925 with almost total reliance on the upper reaches of society as its reader base, and the cartoons inevitably showed wealthy poseurs and stuffed tuxedos, dropping bons mots on their way to the theatah.

Only later, during the sobering modern wars of the century, did the humor begin to take notice of the real class structure of the city and, by extension, the country. In fact, until the ’60s, it’s fair to say that The New Yorker remained parochially New York, if such a thing is possible.

Here, most prejudices are formed by seldom leaving the city – once described as a small island off the coast of the United States. The cartoonists approach politics gingerly, putting strong opinions in the mouths of children or characters we don’t have to take seriously. The blame is softened by the source, and it’s sometimes an annoying mannerism.

Nowadays, of course, political correctness has taken a variety of subjects completely off the artist’s table: jokes about the poor, and about servants of color, about the relative intellect of the genders, woman drivers and so on – all gone.

There are distinct surviving trends, however, some that follow the times and some that are unique to The New Yorker. Robert Mankoff, the cartoon editor and compiler of this tome, must be the world’s expert on these categories, having edited other collections on lawyers, cats, dogs, and doctors.

At first, the cartoons were unabashedly European in nature, drawn by people (mostly men) who had actually studied anatomy and physiognomy.

The ideas for the cartoons were supplied by others. In fact, it surprised fans to read in his obituary a few years ago that the master cartoonist, George Price, a fixture for decades in the magazine, had contributed only one joke to the thousands of cartoons he published.

The book also describes the odd editorial process that accompanies the cartoons, and it’s not like editing prose. The discovery and refining of a funny idea, and matching it to a certain moment captured in the drawing, are unexplainable, although Mankoff makes valiant efforts to do so.

For one thing, Mankoff says, you have to forgive many failures in order to see the one drawing that really works. (By the way, he’ll give $10 to anyone who finds a cartoon missing from this compilation.)

That The New Yorker survived the demise of other general-interest magazines in the face of television’s growth was due to its beneficent publishers, the Fleischman family, and its loyal readers. (The magazine is now owned by Condé Nast and has been famously unprofitable in recent decades.)

If there’s one trend in this book to bemoan, it’s that the artwork has gotten worse, or at least less important. Real drawing is rarely taught in this country any more, and much draftsmanship is celebrated for its distinctive quality, even if awful, rather than for skill with a line. That trend doesn’t make the cartoons any less funny, but something is missing.

Even so, this book is a major achievement, and you can certainly rest easy knowing that you won’t have to buy another collection for a while. And if your subscription lapses for a bit, you’re all set in the cartoon department.

By Jeff Danziger

The Christian Science Monitor