GILROY

– The group responsible for drafting a plan to save farmland in

Gilroy is showing signs of resistance toward changes City Council

wants made to the agriculture preservation bill.

Some members of the Agricultural Mitigation Task Force were

ready Wednesday to send a key component of the farmland bill

– the part that determines how much farmland development

triggers mandatory farmland preservation – back to Council

unchanged.

GILROY – The group responsible for drafting a plan to save farmland in Gilroy is showing signs of resistance toward changes City Council wants made to the agriculture preservation bill.

Some members of the Agricultural Mitigation Task Force were ready Wednesday to send a key component of the farmland bill – the part that determines how much farmland development triggers mandatory farmland preservation – back to Council unchanged.

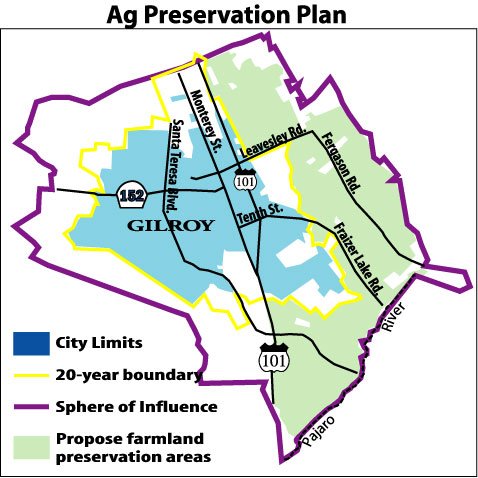

At issue are two main sticking points. One revolves around what part of the greater Gilroy area should be preserved for agriculture. The other has to do with whether even the smallest of farmland owners should pay to develop their land.

The task force, however, stopped short of taking a vote so members could spend the next several weeks becoming more familiar with the litany of amendments the Council, the state, the county and a local open space group want as part of the farmland bill.

“My mind is still turning from the meeting last night,” said Alex Kennett, a task force member and a director for the Open Space Authority. “We all need more information to better understand the concerns.”

The task force’s next meeting will be Jan. 14.

In October, the task force sent a proposed farmland preservation bill to City Council. The plan recommended preserving farmland that lies outside the eastern edge of Gilroy’s 20-year boundary. However, Council wants to consider preserving Gilroy farmland regardless of where it lies in the city.

The plan also recommended that developers mitigate for impacts to agriculture only when they develop 10 acres or more of so-called “prime farmland” and 40 acres or more of “farmland of statewide importance.” The farmland designations are based on soil quality, water availability and other factors.

City Council, however, is open to a more stringent trigger that would make land owners pay a roughly $5,000 fee for each farmland acre they develop. The city would ultimately use those fees to purchase farmland east of Gilroy’s boundaries, from Masten Avenue in the north to the Pajaro River in the south.

Or, the city could pay eastside farmland owners upwards of 90 percent of the land value on condition the owner gives up all development rights in perpetuity. It’s considered a win-win situation by some – ag or open space becomes permanent and the farmer reaps a profit.

For some task force members, City Council’s amendment to include owners of even small amounts of farmland is unrealistic and unfair.

Task force member Kip Brundage, who farms alfalfa on roughly 500 acres on the northeast end of Gilroy, says it’s not profitable to farm anything less than five acres.

“The City Council can save as much farmland as they want, but it’s not going to do anyone any good if they don’t save the farmer,” Brundage said.

Brundage also says a stringent acre-for-acre mitigation fee is unfair, especially for farmers who had always planned to sell their land to developers once the urban line approached.

“Farmland is sort of their 401K plan,” Brundage said of farmers. “They farm the land for 40 or 50 years and make very little money, all along hoping to sell their land when they retire. It’s not fair to take that option away from them.”

The task force is trying to help the city fulfill requirements spelled out by state environmental law as well as follow the city’s own guidelines for keeping urban development from bulldozing too much farmland. Brundage’s concerns are just the tip of a complex iceberg that faces the new City Council which hopes to approve the farmland preservation policy by March 2004.

At Wednesday’s task force meeting, special interests – from Hecker Pass developers to a grassroots open space group called S.O.S. Gilroy – addressed the group with their concerns.

Robert Oneto, a project manager for Gilroy-based developer Ruggeri-Jensen-Azar Associates, spoke on behalf of the Hecker Pass landowners his firm represents. The landowners want to preserve farmland, but they want the option of preserving farmland in the Hecker Pass area and not only on the east side of Gilroy’s surrounding area as the farmland bill proposes now.

Any policy that makes it difficult for Hecker Pass landowners to preserve ag land in their immediate area would disrupt an effort to design a Hecker Pass specific plan that, as it’s drafted now, calls for 100 acres of preserved farmland.

“One of our goals is to preserve the agricultural character of the area, and the only way to do that is to preserve ag land in that area (not only on the east side of town),” Oneto said.

But some task force members and open space advocates don’t want to piecemeal preservation. They argue that focusing preservation in one area makes it easier to keep farmland contiguous, which makes farming more manageable and profitable.

“Imagine trying to manage only the white squares on a chess board,” said Kennett, whose Open Space Authority exists in part to purchase ag preserves.

“Form a land purchasing standpoint, contiguity is mandatory,” Kennett said.

However, Kennett acknowledged that contiguous land may be found all over Gilroy, not just east of the town’s 20-year boundary.

“From a larger-scale management standpoint, you want to preserve as much land as you can as long as it’s suitable for preservation,” Kennett said.