Each morning, millions of Californians remember their lunches,

their car keys and their jackets. Some of them even remember to

walk the dog or take out the trash. But plenty of them forget an

incredibly important item: Health insurance.

Each morning, millions of Californians remember their lunches, their car keys and their jackets. Some of them even remember to walk the dog or take out the trash. But plenty of them forget an incredibly important item: Health insurance.

A choice for some, a necessity for others, one in every five Californians goes without this vital line of defense at some point throughout the year, because of job loss, expense, or the loss of employer-sponsored benefits. And the costs that are being incurred by hospitals, individuals and society at large because of this shift are sizable.

Healthcare is the single biggest share of the U.S. economy, according to info sheets available at Blue Cross and Blue Shield of California’s Web site, www.bcbs.com. Americans spent $1.7 trillion on healthcare costs in 2003 – more than our yearly bill on food, housing or national defense – and costs continue to rise – by 2012, healthcare costs are expected to reach a yearly figure of $3.1 trillion.

Healthcare fraud, such as billing for services not provided, incorrectly reporting diagnoses to maximize insurance reimbursement or using someone else’s coverage to obtain medical services accounted for nearly one third of the money spent on health care in 2003.

When someone loses insurance, debt can creep up quickly, and in the event of job loss, COBRA plans, which allow for the continuation of company health insurance for up to 18 months, are often out of reach.

“In a lot of cases, you’ve lost your job, so it’s not like you can say, ‘Well, I’ll just spend an extra $2,000 or $3,000 on health insurance,” said Shana Alex Lavarreda, a senior research associate at the University of California, Los Angeles Center for Health Policy Research, one of the pre-eminent health policy institutes in the state. “Keeping up the mortgage is important. Health insurance falls through the cracks.”

While private insurance plan coverage varies between companies and policies, spending caps, prescription restrictions and deductibles balance cost for the consumer.

A husband and wife who are non-smokers between the ages of 30 and 39 would pay anywhere from $182 to $1,171 for a plan that would cover them and two children, according to quote generators for Kaiser Permanente, Blue Cross, Blue Shield and PacifiCare insurance companies.

Within that span are HMO’s, PPO’s, deductible-based plans and co-payment options. A $1,500 yearly deductible plan from Kaiser Permanente costs just $333 per month for a family matching the profile above, but the high cost of the deductible is mandatory in order to receive treatment.

It must be paid when the patient first accesses the care chain by visiting a doctor or hospital, even if the only reason for a visit is to get a marble removed from the little one’s nose.

A $25 copay plan, where just a $25 fee is due at each doctor’s visit, jumps the price to $642 per month.

Plans often come with restrictions like coverage caps, making them handy for everyday use, but nearly impossible to use for coverage of a catastrophic illness like terminal cancer.

More than 700,000 people are driven to bankruptcy each year based on their inability to pay medical bills, according to a recent Harvard study. Three-quarters of those 700,000 had insurance at the time of their crisis.

And those without insurance often wait longer to go to the doctor, allowing easily treatable conditions to worsen for fear of the cost they’ll incur for treatment and services. This means they come in sicker and are usually in need of greater care.

And while many moderate- to low-income children are covered under state programs with federal matching funds like Healthy Families, cuts in spending have hampered efforts to get word to the parents of potential participants of these programs’ existence.

Of the 782,000 uninsured children in the state as of 2003, 26 percent were eligible for Healthy Families, said Jeanne Brode, legislative coordinator and public information officer for the Managed Risk Medical Insurance Board, which oversees healthy families and several other state-sponsored health programs.

Parents other than pregnant mothers are not able to receive the same low- or no-cost health insurance, said Brode, a deficiency in the programs that can wind up affecting children by lowering their quality of care or forcing a parent to miss more days of work than he or she can afford.

Moreover, qualification is based on the federal poverty line, excluding many potential recipients who barely make ends meet in expensive regions like Northern California, said Lavarreda.

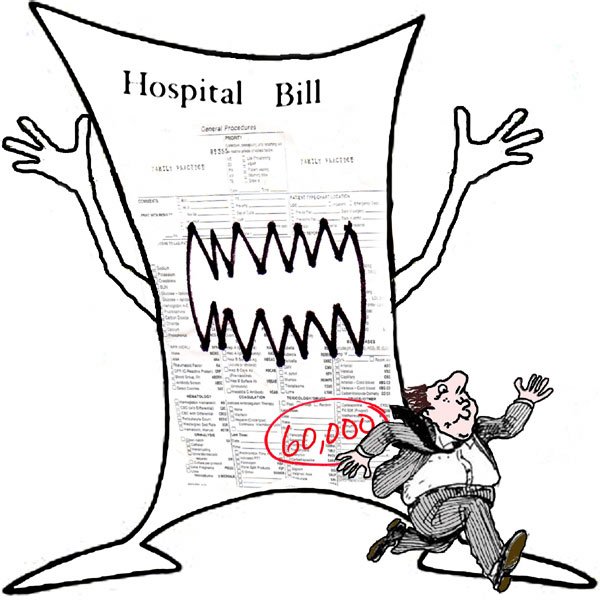

“A lot of people have this conception that if someone shows up in an ER, and they can’t afford to pay, the hospital just writes it off,” said Lavarreda. “The hospitals can’t afford to do that. They show up in the ER, they get care, and they get this humongous bill.”

A program called County Health Initiative Matching has been proposed for implementation in July 2006 and would cover parents living at 100 percent to 200 percent of the poverty line, but the solution could be of even less help to hospitals than the current situation.

Hospitals are left to deal on their own with the shortfalls in reimbursement rates within California. Losses within the state alone climbed to more than $600 million in 2004, forcing the closure of six hospital trauma centers within the year, according to a statement issued by the California Medical Association in September.

The San Jose Medical Center, which served more than 96,000 patients per year prior to its September 2004 closure, is just one in a line of hospital closures across the country.

These disruptions in care force other hospitals to take on even more patients, slowing services and depleting the quality of care in remaining ER’s.

Caught between broke patients and low reimbursement rates for care provided through state and federal programs, hospital administrators know patients aren’t the only one’s feeling the sting.

“Our reimbursement rate for Medical is 13 cents on the dollar,” said Vivian Smith, a spokeswoman for St. Louise Regional Hospital in Gilroy. “For Medicare, we get 17 cents on the dollar.”

Like many other hospitals, St. Louise has been forced to cope with heavy losses.

Last year, the hospital’s net losses for Medicare and Medical patients were $3.5 million. Saint. Louise also spent $200,000 on charity care, which is care for those who could not afford to pay them back and is not covered by the state.

In 2005, the figure for Medicare/Medical losses is expected to grow another $350,000, and charity care is expected to double, said Smith.

“It’s the Daughters’ (of Charity’s) mission to serve the poor and we do our best to do that,” said Smith. “It doesn’t matter how many people come to us. It’s our mission.”

Officials from Hazel Hawkins Hospital did not return repeated phone calls in time for the publication of this story.

For more information on the Healthy Families Program, visit www.HealthyFamilies.ca.gov or call (800) 880-5305. For help filling out a program application, call (888) 747-1222 to locate the Certified Application Assistant closest to you.