Duke Ellington probably did not ask Ivie Anderson for her birth

certificate when he hired the singer in 1931, but Fred Glueckstein

sure would like to see a copy for the book he’s writing about the

Gilroy celebrity

Gilroy

Duke Ellington probably did not ask Ivie Anderson for her birth certificate when he hired the singer in 1931, but Fred Glueckstein sure would like to see a copy for the book he’s writing about the Gilroy celebrity.

Vinyl records, photographs and Hollywood films copiously document Anderson’s life as the smoky, plaintive voice behind the Duke’s orchestra for 11 years, but little remains of the soloist’s life before the limelight, when she was just another Gilroy girl.

Back then, during the 1910s, Anderson gamboled about Old Gilroy Street, kicking the can around outside her house (number 363) with her childhood friend, George Porcella. The latter lived across the street at 392, according to his son, Dave Porcella, who still lives there and owns Porcella’s Music & Accessories downtown at 7357 Monterey St. George Porcella took over the 110-year-old business from his father in 1947 and added a musical component to the general store he ran until his death in 1986, when Dave Porcella, 57, devoted the entire store to music, he said.

“My father and Ivie played as little kids, but nobody knew one day she would be so famous, that she would get hooked up with the Duke,” Porcella said Friday in a cramped back room filled with dusty trinkets as he thumbed through a stiff photo album containing yellowed black-and-white pictures of his father and Ivie.

While Dave Porcella said his dad and Anderson did not play music together growing up, pictures of the musical duo also crowd the back wall of his shop. One shows George Porcella – who also played saxophone – gripping a clarinet in the front row of a portrait for the Gilroy High School band before he graduated in 1930, according to Dave Porcella. Another depicts a then-famous, white-dressed Anderson drowned in light and out of focus as she smiles coyly with her arms akimbo and torso twisted.

Dave Porcella, who plays the organ and clarinet, said customers often gravitate toward the frame-haven hanging on the rear wall and that conversations can turn into history lessons.

One of the most popular photos depicts a serious, almost rattled Anderson seated behind a black piano prior to a show 67 years ago. Cigarette in hand, Ellington leans over her right shoulder, temporarily distracted by something out of frame, but a pin-striped George Porcella – who was playing his own gigs at the time with The Merry Makers in and around Gilroy – leans over Anderson’s left shoulder and stares right into the lens, glowing with delight. This was one year before Anderson’s retirement due to asthma, according to various sources, but about 30 years prior, Anderson began taking her first formal voice lessons at St. Mary’s Convent in Gilroy.

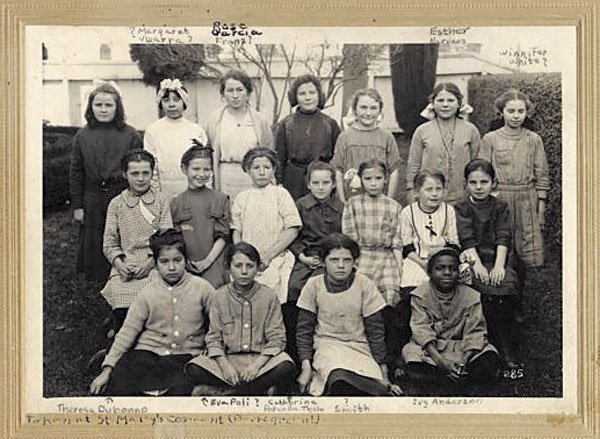

Dave Porcella also has a picture of this: an 8- to 10-year-old Anderson seated grumpily in the front row of her St. Mary’s class. There is no date on the photo, which makes pin-pointing Anderson’s birth date even harder, but various accounts say she attended St. Mary’s from the age of 9 until 13, singing in the glee club and choral society, according to Phil Laursen, an active member of the Gilroy Historical Society and ad-hoc volunteer at the Gilroy Historical Museum, which has three copies of Anderson’s recordings.

While the dates are uncertain, Anderson’s high school education in Gilroy ended abruptly, either when her mother died or her parents separated, whereupon she moved to Oakland with her aunt and uncle before attending an all-black girls finishing school in Washington, D.C., where she studied voice, according to Laursen. Glueckstein, the Maryland author penning Anderson’s biography, could not be reached for comment, but after her stint in D.C., Anderson’s life becomes more navigable.

With plenty of voice training, she returned to California sometime in the early- to mid-20s and sang with Curtis Mosby, Paul Howard, Sonny Clay and briefly with Anson Weeks at the Mark Hopkins Hotel in Los Angeles, according to Solid!, an online encyclopedic source for classic jazz. She also traveled as a vaudeville performer and sang at the Culver City Cotton Club in Los Angeles county before touring Australia in 1928 with Sonny Clay.

Back in America two years later, she began singing for jazz pianist Earl Hines and his orchestra in Chicago, where she finally caught Ellington’s ear one February night in 1931, according to various sources. Her recording debut with the Duke came a year later with the jumpy hit, “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing),” in which Anderson showcased her guttural, yet refined passion for lyrics. Other popular tunes included, “I Got It Bad and That Ain’t Good,” “Stormy Weather” and “Rose of the Rio Grande.”

Harry Carney, Ellington’s baritone saxophonist, characterized Anderson’s on-stage presence as ” ‘angelic and above it all, yet backstage and on the bus, hotels and restaurants, everywhere she was always regular 100 percent. There was no side of (pretentiousness) to her,’ ” Nat Hentoff quoted him as saying in his April 2001 article for The Jazz Times.

Cinephiles might remember her singing “All God’s Chillun’ Got Rhythm” in the Marx Brothers’ 1937 film “A Day at the Races,” in which Anderson played a washerwoman, according to the online movie database IMDB.com. Critics have argued that she transcended the small role with her calm charisma and Billie Holiday-esque voice, but the film rooted her presence as Ellington’s longest-lasting soloist. She also appeared in “Belle of the Nineties” with Mae West.

Despite its trajectory, Anderson’s career ran out of steam in August of 1942 due to a crippling case of asthma. Sundry sources also indicate that she then moved to Los Angeles and opened a chicken restaurant before her asthma-induced death Dec. 28, 1949. Before she retired down south, however, Dave Porcella said he thinks she had time for one more snapshot outside his father’s old house at 392 Old Gilroy St.

The photo portrays a quizzical Anderson sandwiched between George Porcella and his sister, Ann, in what Dave Porcella said he believes took place in the early ’40s. Regardless, Anderson, with her fluid rhythms and feathery cadence, left behind a small wake of friends in Gilroy and a much larger wake of songs in the golden age of jazz.

Glueckstein – whose book is entitled, “Ivie Anderson: The Life and Times of Duke Ellington’s Greatest Vocalist” – and Laursen would appreciate any information and/or photos about Anderson’s life, especially something that indicates her exact birth date. Laursen can be reached at 846-0446.