I’d like to imagine that had he lived and journeyed west to

California after the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln would have visited

New Almaden. The sleepy village lies in a narrow canyon tucked in

the Pueblo Hills a few miles northwest of South Valley.

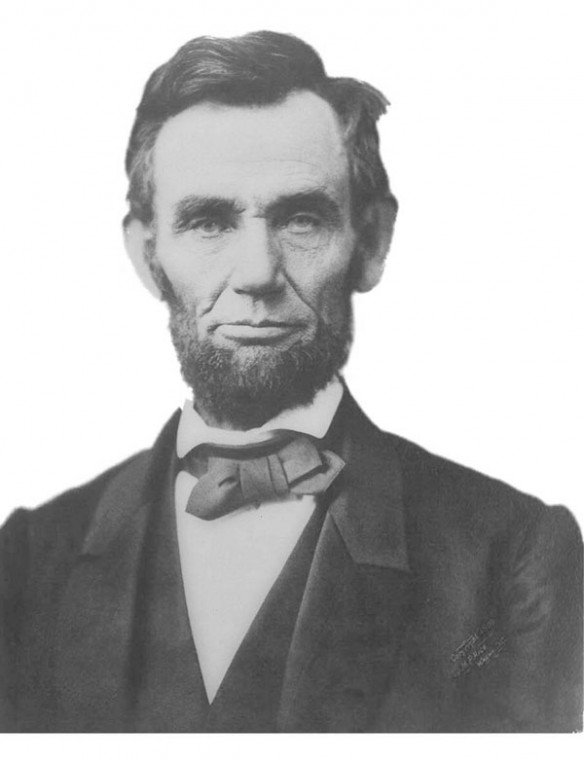

I’d like to imagine that had he lived and journeyed west to California after the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln would have visited New Almaden. The sleepy village lies in a narrow canyon tucked in the Pueblo Hills a few miles northwest of South Valley.

It’s a footnote in history now, but New Almaden has a fascinating link to the Great Emancipator. In the summer of 1863, Californians felt enraged over a truly bonehead decision Lincoln made concerning taking over this mining town. An order he’d issued over its ownership almost cost him the Civil War.

The Ohlone Indians for years had used cinnabar from the New Almaden canyon to paint their bodies. Cinnabar is a source of the toxic element mercury (also known as “quicksilver”). In 1846, Captain Andres Castillero of the Mexican Army realized the location’s significant mineral source and obtained ownership from the Mexican government.

The outbreak of the Mexican-American War, however, forced Castillero to shift focus to military matters. He sold the mines to Barron, Forbes Company, an English textile firm based in Tepic, Mexico.

Alexander Forbes named the site “Nuevo Almaden,” after the Almaden mines in La Mancha, Spain, which had produced vast amounts of mercury since the days of ancient Rome.

Quicksilver acts a bit like a magnet in attracting gold. So the establishment of the mine just prior to the Gold Rush was a lucky accident. Without New Almaden – the richest mercury mine in North American history – the 49ers might never have collected the vast amounts gold they did.

In 1850, inspired by this sudden great need for mercury, Henry Wager Halleck, a captain of the Army Corps of Engineers, hired on to mechanize and manage New Almaden. Halleck later served as Lincoln’s chief of staff during the Civil War.

New Almaden played a crucial role in helping the Union achieve victory during this bloody war. Without its mercury, California and Nevada could never have supplied enough gold and silver to help finance the Union Army. The mercury was also used in producing material such as blasting caps.

So important were the lucrative New Almaden facilities to the war effort that greedy New York speculators pushed Lincoln to seize the mines for the United States away from Barron, Forbes Company. The American investors saw an opportunity of making millions for themselves if they owned the rights to the mines.

In early July 1863, Lincoln signed the writ of ejection. The order was telegraphed to federal agent Leonard Swett in San Francisco. Swett and a district marshal named F.F. Lowe immediately headed to New Almaden to deliver the writ. Meanwhile, troops at San Francisco’s Presidio prepared to take over the mines by force if necessary.

When Swett and Lowe reached New Almaden’s town gates, they were met by company Superintendent Sherman Day – and a gang of irate miners pointing shotguns and pistols at them. Feeling unwelcomed, Lincoln’s two agents quickly trekked off to safer territory.

News of the standoff spread. Californians felt alarmed the federal government might dare seize private property. Speculation grew. Maybe, some suggested, Lincoln planned to seize other quicksilver mines throughout the state – or even gold and silver mines.

Although loyal to the Union, California’s fiercely independent population also had a number of people supporting the Confederate cause. San Juan Bautista, for example, was full of Southern sympathizers from Texas. The savvy Lincoln realized his ordering federal troops to seize New Almaden might damage or even destroy California’s loyalty. And if California left the Union, all its gold and Nevada’s silver might soon find its way into Confederate coffers. The worst scenario was a potential West Coast front that would spread thin Union forces and extend the Civil War.

Lincoln wisely backed off in the showdown over New Almaden. To put in place some desperately needed spin control, the president sent his San Francisco agents this telegram on August 17, 1863:

“There seems to be considerable misunderstanding about the recent movement to take possession of the ‘New Almaden’ mine. It has no reference to any other mine or mines.

“In regard to mines and miners generally, no change of policy by the Government has been decided on, or even thought of, so far as I know.

“The ‘New Almaden’ mine was peculiar in this: that its occupants claimed to be the legal owners of it on a Mexican grant, and went into court on that claim. The case found its way into the Supreme Court of the United States, and last term, in and by that court, the claim of the occupants was decided to be utterly fraudulent. Thereupon it was considered the duty of the Government by the Secretary of the Interior, the Attorney-General, and myself to take possession of the premises; and the Attorney-General carefully made out the writ and I signed it.”

The tense situation came to a resolution on Aug. 26, 1863, when Baron, Forbes Company sold the property to American owners for $1.75 million. The mines are now part of New Almaden Quicksilver County Park operated by Santa Clara County.

The last letter Lincoln ever wrote expressed his wish to one day see California. No doubt he would have enjoyed a day trip from San Francisco to New Almaden. Perhaps his friend Henry Halleck would have given him a personal tour. Walking through the famous mercury mines, Lincoln would surely ponder his potentially disastrous presidential decision of July 1863. For the nation’s future, he was fortunate New Almaden didn’t cause the Union to lose California.

Even great leaders like Abraham Lincoln make foolish decisions based on faulty information from advisers. But as New Almaden shows, Lincoln’s greatness in character led him to admit his mistake and change his course of action before the problem grew worse.

Perhaps this Saturday on Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, the present White House occupant – a man who made some truly bonehead decisions of his own concerning taking over Iraq – might ponder this important lesson from our 16th president.