Decades ago, Gilroy was no place for Jews. When Pinky Bloom

moved to town in 1962, she knew of only one other Jewish family

– and it left town.

Gilroy – Decades ago, Gilroy was no place for Jews. When Pinky Bloom moved to town in 1962, she knew of only one other Jewish family – and it left town.

“There was nowhere to worship,” Bloom said, shaking her head. “They couldn’t take it.”

Grocery stores didn’t carry matzah or Havdalah candles. Kids jeered at her kids, and told her 9-year-old daughter she killed Jesus. Later, she battled the school board over a policy that let Catholic children leave school for catechism, but banned her son from bar mitzvah lessons.

“There was a vague sense of not belonging, growing up,” agreed Bloom’s daughter, Margene Bloom-Roza. “Like we weren’t really part of Gilroy.”

Even today, 30 years after its founding, South County’s only Jewish congregation is still trying to find a place to call home – literally. Sixty families flock to Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur services on the Jewish calendar’s two holiest days, crowding into borrowed halls at churches, schools and social halls.

“There’s not a wholly Jewish spot anywhere in South County except in the cemetery,” remarked Michael Oshan, congregation president, “and you know, that’s not quite the same.”

Without a concrete home, South County’s Jews have built community in other ways. In the 1960s, Bloom became the de-facto Jewish network of Gilroy. More than a decade later, when Michael Oshan moved to town and the Welcome Wagon greeted him with well-wishes and coupons, asking, “Which church do you belong to?” his answer prompted, “Go see Pinky at the PG&E plant.”

“The few Jews there were weren’t necessarily wearing their Judaism on their sleeve,” said Oshan. Bloom was the exception. Her brush with the school board brought Judaism into the spotlight in Gilroy, and made her a notable name in town. Even better, she won. Her son was eventually allowed to leave for his lessons, just as Catholic kids did for theirs.

“It was quite a feather in our cap,” she said proudly. “I wasn’t going to take no for an answer.”

Years later, Dispatch owners Jerry and Ellen Fuchs placed a notice in the paper, asking Jewish families to meet. A dozen people gathered in their living room, and gave themselves a lengthy name: the South Santa Clara County Jewish Community. A year later, in February 1977, they incorporated under that name.

No one is sure when the congregation dropped the clunker and became Emeth – a Hebrew word that means truth, said congregation historian Jack Shorr. Paging through seven massive binders of synagogue fliers, newsletters and other records – an eighth binder is in the works – he can’t put his finger on when and how Emeth got its name. Nor do Bloom or Oshan know.

But the name boosted Judaism’s profile in Gilroy, said Oshan. Off-color jokes dwindled. The newspaper ran ads for Nob Hill Grocery boasting ‘Passover challah’ – a well-intentioned oxymoron for a Jewish holiday that bans bread such as challah.

“Some people, to this day, don’t get it,” said Oshan. “You’d hear invocations at Little League or city meetings with a very, very Christian flavor to them. They’re not doing it consciously. They’re just totally unaware.”

With more than 100 newspaper articles about Congregation Emeth packed into those weighty binders, Shorr is surprised that people still think there aren’t Jews in Gilroy. To be fair, their numbers remain small. In a congregation that swells to hundreds on major holidays but averages around 20 or 30 people at typical events, each person becomes important.

“Everyone takes on a more active role,” said Oshan. “When you live in a community with a lot of Jews, you tend to take it for granted.” Oshan is originally from the Los Angeles area, where Jewish families were common. “Here, you can’t.”

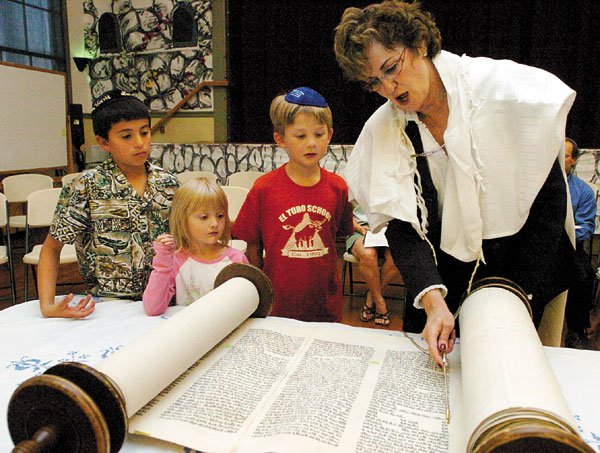

The do-it-yourself attitude has seen Emeth through a succession of rabbis, many of them students. Debbie Israel, a student rabbi from Houston, recently signed a two-year contract with Emeth. She leads services at Carden Academy in Morgan Hill on Friday nights, using a portable Torah and portable Ark, the traditional cabinet where the Torah is kept. Unlike most rabbis, she doesn’t have a regular office where congregants can stop in casually to chat.

It’s one of many reasons that Oshan wants another Jewish spot in South County – outside the graveyard.