Final four members of America’s only populated Shaker village,

in rural Maine, agree to a preservation plan to protect the enclave

from subdivisions

By Sara Miller Llana, The Christian Science Monitor

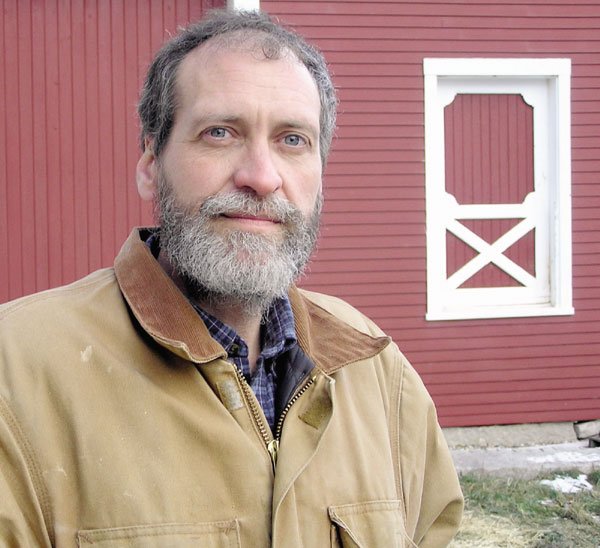

New Gloucester, Me. – Wafts of fruitcake, fresh from the oven, lace the brick Dwelling House, built in 1883. In the barn across the field, as the sun hangs low on a winter horizon, three pigs gleefully scuttle toward Brother Arnold. “Hello kids, hello kids,” he coos, patting their rumps as if they were pet dogs.

In many ways, life has changed little in this pastoral patch of southern Maine, where the Shaker community has toiled for more than two centuries. That’s why Brother Arnold winces when he is told they are vanishing.

“Everyone says, ‘poor Shakers,’ ” he says. “People come here, and say we are gone.”

You could, of course, be forgiven the assumption. This is the last populated Shaker village in the country. The other 17 have disappeared or become museums. And here on Sabbathday Lake, on 1,800 idyllic acres of forest, apple orchard and pasture, only four Shakers remain, pledging celibacy, and, in their founder Mother Ann’s words, to put their “hands to work and hearts to God.”

Brother Arnold, Brother Wayne, Sister June and Sister Frances are the last possessors of the Shaker tradition, a responsibility they are reminded of each day as they share meals across long, wooden tables, or when they say goodnight and head to their separate rooms. Yet it is not with a sense of doom, but determination, that they uphold the tenets of their centuries-old faith – and adapt to the realities of the future.

Sometimes that means looking outward in ways both pragmatic and novel. Recently they signed a $3.7 million preservation plan with a consortium of conservation groups in Maine to ease their tax bills and protect their property from being turned into subdivisions. “Friends are increasingly important to this community,” says Brother Arnold, patting their golden retriever, Chase.

The United Society of Believers, dubbed Shakers because they shook and trembled during 18th-century worship, was never a group of vast numbers. Ann Lee founded the Protestant sect in 1747 in England, but, because of persecution, they immigrated to the United States in 1774. Here they formed communities stretching from Maine to Florida. At their height before the Civil War, they numbered 5,000, many of them orphans.

Most of the world has become acquainted with Shakerism through the simple, solid furniture the group produced over the decades. “There has been an incredible love, almost a romantic love and embrace of the material culture of the Shakers,” says Stephen Stein, an emeritus professor of religion at Indiana University in Bloomington.

While their wooden chairs and tables have become American icons, much of their ethos is quintessentially Yankee. They embrace progress, and their inventions, such as the clothespin or flat-bottomed broom, are hallmarks of the value they place on efficiency. Though they are often confused with the Amish, Shakers use modern conveniences – they share three vehicles and use the Internet – and practice communal living in a way that can make life less simple.

At Sabbathday Lake, where only trucks rumbling down Route 26 interrupt a quiet afternoon, the four awake to morning prayers and set to work. They tend to 30 sheep, nine cattle and three pigs. They gather gifts for the needy and lay out hydrangeas to dry for wreaths. They make their own yarn, cook and clean, and maintain 19 historic buildings. The great bell atop the Dwelling House summons them to meals.