To say that this election season has been highly charged is like

saying Boston Red Sox fans are fairly happy right now. On top of

our usual array of important ballot measures and local campaigns,

the presidential race has been called

”

the most important in our lifetime

”

by both Republicans and Democrats. If it seems like everybody

has an opinion on the election, that’s not far from the truth

– pollsters predict that the percentage of voting-age Americans

casting ballots will be the highest in years, while the number of

self-proclaimed undecideds going into election day is at a record

low.

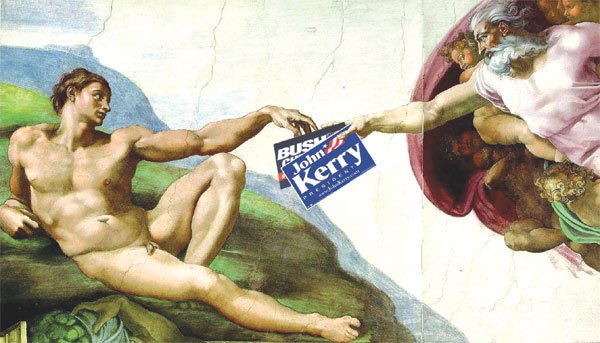

To say that this election season has been highly charged is like saying Boston Red Sox fans are fairly happy right now. On top of our usual array of important ballot measures and local campaigns, the presidential race has been called “the most important in our lifetime” by both Republicans and Democrats. If it seems like everybody has an opinion on the election, that’s not far from the truth – pollsters predict that the percentage of voting-age Americans casting ballots will be the highest in years, while the number of self-proclaimed undecideds going into election day is at a record low.

Members of faith communities have as much of a stake in the race for the presidency as anyone else. From judicial appointments to the wars on terror and poverty, moral issues merge with political agendas, becoming distilled for the nation in its choice to fill the highest job in the land. But for all the importance people of faith are placing on this election, the churches, temples, mosques and synagogues where they worship walk a fine line when it comes to discussing politics.

Religious organizations that are exempt from federal income tax under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code are generally permitted to “lobby” for or against proposed legislation but are absolutely prohibited by law from engaging in “political activity” for or against an individual candidate for office, or risk losing their tax-exempt status.

“The distinction (between lobbying and political activity) is important,” says Rev. Anita Warner, pastor of Advent Lutheran Church in Morgan Hill. “We do not endorse political candidates from the pulpit.

“But from a faith perspective we are bound to speak to the issues. We are a congregation of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. This church has adopted social statements in some areas that are intended to teach and to guide legislation on issues, as well as promote healthy discussion of the common social issues before us.

“As a whole church, we have committed ourselves to open, passionate and respectful deliberation on challenging and controversial issues of contemporary society. We address the issues faced by the people of God, in order to equip them in their discipleship and citizenship in the world.”

Rev. Dan Derry of St. Mary Catholic Parish in Gilroy says that the Catholic Church, “as a tax-exempt organization … can’t endorse candidates, but we are able to share the church’s teachings” as they relate to issues being discussed in a campaign or being considered for legislation.

He also cites a more practical reason for refraining from overt political posturing from the pulpit: “Knowing that you’re pastoring for people of both parties, you’d be foolish to endorse an individual.”

Says Rev. Duane Cashion of Grace Bible Church in Hollister: “We don’t change our focus because of whatever politics are in the air. We truly believe our job here is to preach the word of God. Politics is secondary to that. Obviously, moral issues are something we need to address, but we work through Scriptures to do that.

“We recognize that the Bible says that (God) will set up kingdoms and tear them down, and we put our faith in God’s sovereignty.”

Of course, there are some adherents who avoid politics altogether, whether it’s classified as lobbying or political activity. Hamilton Breton of Gilroy’s Baha’i community is as tough to get to commit to a political position as one would expect of an adherent to the tolerant, universalist religion that claims some 8 million members worldwide. With no clergy, sacraments or rituals, the Baha’i faith has essentially no pulpit from which to preach.

“One tenet of the Baha’i faith is that we don’t get involved in partisan politics,” says Breton. “We like to side with whatever is best for the country.”

About as specific as Breton will get is to say, “We support a just government that is rightfully elected.”

Blurring the line

If most local religious institutions seem to be strict in their interpretation of the rules regarding their tax-exempt status, on the national level, groups are waging a fierce fight over alleged transgressions of these rules. Americans United for Separation of Church and State (AUSCS), a group that monitors religious 501(c)(3) organizations, filed a complaint with the IRS in July against Rev. Ronnie Floyd, pastor of the First Baptist Church of Springdale, Ark., and, just this week, against Rev. Ernest C. Morris Sr. of Mount Airy Church of God in Christ in Philadelphia.

Floyd is accused by AUSCS of delivering a sermon in support of re-electing President George W. Bush, while Morris stands charged with making a plea from the pulpit for John Kerry.

But just what constitutes such transgressions can be a gray area, say defenders of Floyd, Morris and other religious figures accused of committing them.

“It would be fairly easy for any church organization to blur the rules,” says Derry. Indeed, Morris is accused of stumping for Kerry when he said at a religious service to about 1,500 worshippers, “I can’t tell you who to vote for, but I can tell you what my mama told me last week: ‘Stay out of the bushes.'” Mounting the classic defense of the double-entendrist in a press conference, Morris asked his accusers, “Did I give anybody’s name? What are they talking about? I’m very sorry if that’s what they read into it.”

Two days ago, AUSCS spokesman Rob Boston countered, “It may have been said in a punning way, but it’s still clear he was trying to endorse John Kerry and oppose George Bush.”

Another recent “blurring of the rules” occurred when several Catholic bishops publicly announced that they would deny Kerry, who is Catholic, communion because of his stance on abortion. Critics of the bishops accused them of violating the 501(c)(3) rule by, in essence, removing church ambivalence over who is the next president.

“They’re dead wrong,” says Derry of the bishops’ proposed denial of communion to Kerry, but argues that they do not represent the official Catholic Church position by a long shot. “They’re no more than five out of 250 bishops (in the United States).”

He adds that the Catholic Church has made it clear that it is not in the business of raising one issue above all others on the moral scale. “There are those who hold that abortion as a single issue is the most important, but the Catholic bishops have come out with a document that says that the whole range of moral issues should be considered and a person should make their decision based on that.

“Issues of poverty, war, hunger and already-born children are just as clearly pro-life issues as abortion,” Derry says.

Meanwhile, other advocacy groups prefer not to dance around the gray area, but question the very heart of the 501(c)(3) rule itself. Churches in Ohio and Pennsylvania were instructed by the IRS that they could not host a tour by the Christian Defense Coalition, whose director, Rev. Patrick J. Mahoney, had planned to lead congregations in praying for a Bush victory during evening services over the last two weeks before the election.

“This is rank censorship,” Mahoney told the press. “If churches felt compelled to pray for Senator Kerry, they should be able to do that, too.

“Now we have the IRS not only limiting what can said behind a pulpit in terms of electioneering, but churches aren’t even allowed to pray the dictates of their consciences.

“You hear people talk about the separation of church and state. This is a massive violation of the separation of church and state from the standpoint of the government intruding on the private dictates of churches.”

To this, the AUSCS and others reply, any church is free to say whatever they like about a political candidate … they just can’t do that and have tax-exempt status at the same time.

The roots of the rule

The principle of the separation of church and state is certainly subject to interpretation, say both secular and religious advocates.

“I believe that if a nonprofit religious organization such as ours becomes part of a political campaign, then it should lose its tax-exempt status,” says Warner of the Advent Lutheran Church. “But I won’t use the argument specific to the separation of church and state.

“Separation of church and state’s genesis was intended to protect faith communities from government control, so it works in the reverse direction.”

As for the supposed intent behind the 501(c)(3) rule, according to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ (USCCB) “Political Activity Guidelines for Catholic Organizations”:

Contrary to popular belief, the section 501(c)(3) political campaign activity prohibition is not a manifestation of Constitutionally-mandated “separation of church and state.” The prohibition applies to all section 501(c)(3) organizations, not just churches and religious organizations. The political campaign activity prohibition was introduced by then-Senator Lyndon B. Johnson during Senate floor debate on the 1954 version of the tax code. LBJ appears to have been reacting to the support provided Dudley Dogherty, his challenger in the 1954 primary election, by certain tax-exempt organizations. There is no legislative history to explain definitively why LBJ sought this amendment to the IRC. However, there is no evidence that religious organizations were his targets.

Indeed, Johnson’s original intent, if the USCCB is correct about it, could use some updating. The rise of the “527’s,” a relatively new classification of tax-exempt non-profits which can engage in all manner of political activity, has been alarming to many political observers who believed the McCain-Feingold campaign finance legislation would stem the tide of enormous amounts of money poured into political campaigns, a great deal of it doled back out as negative, divisive advertising.

The 527’s, unlike the 501(c)(3)’s, are able to endorse one candidate over another, and do so with as much financial clout as they can muster without falling foul of the new campaign finance rules, because they are not officially aligned with candidates. That means just as much money and partisan PR spin as ever is being thrown at campaigns despite the hopes of campaign finance reform supporters. And it means that the stakes in the U.S. political arena remain just as high, just as brutal and just as seemingly no-holds-barred for Americans, churchgoing Americans not excepted.

As religious organizations and the faith communities they represent struggle with their role in politics, and secularist watchdog groups like AUSCS play “snoop in the pew” to catch clergy crossing the political line, both might occasionally step back from the fray and wonder what it would be like if more of us were like the members of the Baha’i faith. As Breton notes contentedly: “There’s no political discussion at all in our community.”