With Gilroy’s tiered structure, the average resident pays twice

for water what city pays

– building ample reserves

Gilroy – Every time someone in town turns on the tap, money flows into the city’s coffers.

Following the lead of the Santa Clara Valley Water District, Gilroy has been steadily raising water rates for years to build ample reserves for future capital projects, even in years when its water-related expenses have gone down.

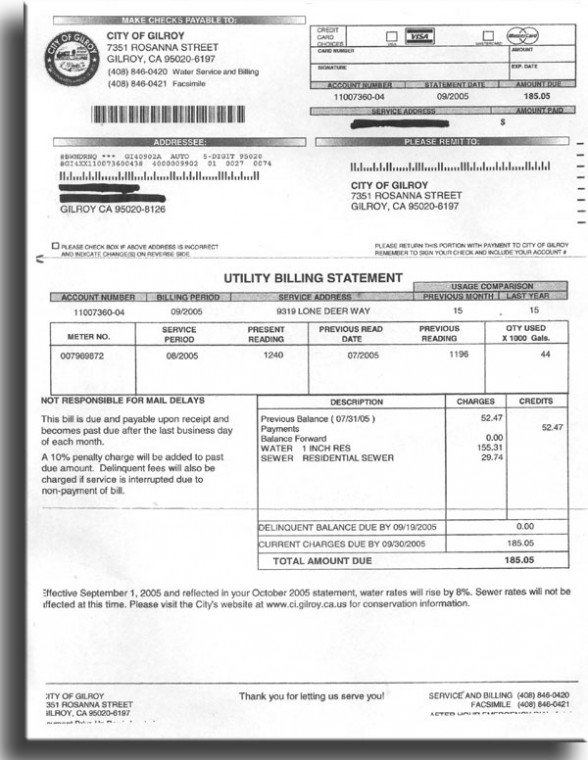

Last month, the city raised rates 8 percent. In 2004, water rates went up 15 percent. In 2003, 10 percent. And while the rate increases match the district’s, the burden is much greater on Gilroy residents because even the stingiest water user pays more for water than the city does.

Under the city’s tiered pricing structure, the average resident pays twice what the city pays for its water, and it’s not unusual for residents to pay as much as five or six times what the city does, especially in the summer. Two years ago, residents paid $47.70 for 25,000 gallons of water. Though the city pays just $16.50 for that much water, 25,000 gallons now cost residents $59.25. Pipe and sewer fees push the total over $90.

Meanwhile, the capitol water projects reserve fund will hit $7.84 million next summer, or more than the city’s annual water services budget.

City Administrator Jay Baksa said the reserve fund ensures that the city will be able to maintain and replace an aging water system in coming decades and will rise by about $600,000 a year until it caps at the value of the city’s water infrastructure assets. He called the similarity between the district’s and city’s rate increases “a coincidence.”

“The question is, what’s most prudent,” Baksa said. “Do you err on the side of having it or do you err on the side of not having it? We’d be criticized if we needed the money and it wasn’t there.”

By contrast, the city of Morgan Hill, with a water budget roughly the same as Gilroy, aims at an annual capital projects budget of about $1.2 million and total reserves of about $4.3 million.

Morgan Hill residents pay $42.09 for 25,000 gallons of water, but are saddled with a 15 percent surcharge to clean the contaminant perchlorate from the city’s water supply. Finance Director Jack Dilles said the city decided on lower, targeted reserve levels to prevent unchecked reserves growth.

“There is no right number, and as a conservative person, I would like to have more in the bank,” Dilles said. “Having said that, I wouldn’t say raise rates just to keep that number at a certain level. You have to be reasonable.”

Baksa said the amount funneled into the capital reserve fund was suggested by an independent auditor. Unlike Morgan Hill, Gilroy has no policy guiding reserve levels, but in practice the city also maintains an operating reserves fund equal to 12 percent of the annual water budget.

Its total current water reserves are more than $9 million. That operating reserve money is earmarked for unexpected expenses.

The capital reserve money is being used as collateral on a bond for the city’s new police station, sports park and public works facility. In some scenarios it may be used to pay down the $45 million bond.

Though water revenue is supposed to be used only for water-related projects, Baksa said the city’s plans “pass all the legal tests.”

In another twist, the city’s water budget relies on residents failing to conserve water.

Exercising reasonable care, the average family of five should use about 14,000 gallons in an average month. But according to Mike Dorn, the city’s treasurer, the city doesn’t break even on its water customers until they approach 15,000 gallons a month. Residents who use more than 15,000 gallons a month put the city’s water budget in the black.

“Our rates aren’t fair. They’re designed that way intentionally,” Dorn said. “It’s a punitive measure for using too much water.”

The city charges progressively higher rates for water usage up to 5,000, 15,000, 30,000, and more than 30,000 gallons. The system dates back to the drought of the early 1990s, when the city tried to discourage water consumption with citations for uses considered wasteful, like washing a car on the street.

“There was a huge public outcry and we only conserved about 5 percent,” Dorn said. “So we adopted these rates.”

Water rates are also higher for residents of Eagle Ridge and Country Estates, at the top of Mantelli Drive, because the city pays more in electricity to pump the water up the hillside. Electricity is one of the largest elements of the city’s water costs, second only to the fees paid to the water district. Maintenance, staffing and billing are the other major expenses.