With the impending end of summer 2008 upon us this Labor Day

weekend, I’d like to tell you how Heinrich Alfred Kreiser spent his

vacation days.

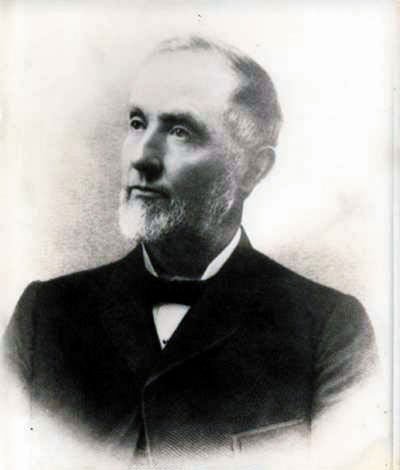

With the impending end of summer 2008 upon us this Labor Day weekend, I’d like to tell you how Heinrich Alfred Kreiser spent his vacation days. He retreated west of Gilroy to a prominent 1,897-foot peak at the southern end of the Santa Cruz Mountains. There, he relaxed with his family among the towering redwood trees covering Mt. Madonna.

Now, you might be wondering, who the heck is Heinrich Alfred Kreiser and what’s his special connection to this South Valley landmark? Well, if it weren’t for this ambitious fellow, we might not now be able to enjoy the Mt. Madonna County Park along Hecker Pass.

Kresier was born in the town of Brackenheim, Württemberg, Germany on July 21, 1827 and grew up on a farm in that region. When he was a lad of 14 years, he tired of his daily duties watching over a flock of geese. He left home and spent a couple of years in Holland and England. He then sailed on a 60-day voyage to New York City. Arriving penniless, he found work as a butcher.

Gold was discovered in California in 1848, and that lured Kreiser on a west-bound journey with thousands of other Argonauts. He didn’t quite make it. In Panama he met an American and the two started a business together. Unfortunately, Kreiser took ill with a serious case of tropical fever. While he laid sick, his business partner ran their enterprise into heavy debt. After paying all the bills, Kreiser had barely enough money to purchase ship fare to San Francisco.

Kreiser arrived in the city in 1850. With only five dollars in his pocket, he walked along Montgomery Street seeking a job. By the end of the day, he was employed as a butcher. By the next year, he went into business of his own when he opened a retail butcher shop on Jackson Street. He soon found himself journeying about the Bay Area region building up his knowledge of the California cattle industry.

Less than a decade after his arrival in the Golden State, Kreiser had started building up a cattle empire by buying ranches in Santa Clara County and the San Joaquin Valley. In 1860, he married a cultured woman named Sarah Wilmarth Sheldon, and the couple had two girls and a boy. Starting in 1859, he also started purchasing land on the summit of Mt. Madonna and eventually owned about 13,000 acres of the redwood-covered slopes. There for his family’s summer recreation, he built a magnificent vacation retreat. It included a 3,600-square-foot ballroom and a “cottage” with seven bedrooms. A small cement pond was built for the kids to cool off on hot days.

At one point in his life, Kreiser owned more than 1 million acres of land and 1 million cattle. He was the largest landowner in the world for a while during the 19th century, controlling the equivalent of real estate twice the size of Belgium. He was also a great benefactor to the South Valley region, giving generously to various causes in the Gilroy community.

You say you never heard of Kreiser? Well, maybe you know him by another name. He involuntarily changed his name due to a little fraud he committed. When in 1849 he stepped aboard the New York ship heading to Panama, he was carrying a ticket he’d purchased from a shoe salesman who, at the last minute, had abandoned the idea of going on the voyage. As Kreiser headed up the gangplank, he noticed the ticket had on it the words “NOT TRANSFERABLE.”

The purser checking the passenger list asked Kreiser, “Name, please?” Gulping at telling a lie, Kreiser gave the name of the shoe salesman which was written on the ticket: “Henry Miller.” Afraid that he might be caught, he continued to use the name until his business made it impractical to go back to his real name. Eight years after reaching California, the state legislature voted to legalize the change.

Gilroy’s Miller Avenue is named after the famous “Cattle King” who built a summer mansion on top of Mt. Madonna. His family’s summer retreat, unfortunately, is long gone. All that remains are cement steps and stone walls slowly decaying from the elements. Miller’s vacation home land was purchased in 1927 by Santa Clara County and turned into a popular recreational park.

Exploring the Miller ruins, I’ve envisioned the grand parties he and his wife must have held here. Their guests arrived on horse-drawn buggies or magnificent steeds. The couple’s children wandered with their friends enjoying the mountain-top marvels.

Kreiser, the German immigrant who came to California virtually penniless, no doubt enjoyed his summer retreat under the redwoods. It provided a well-earned reward after all his days of labor becoming America’s greatest cattle baron.