A regular eye exam isn’t a painful procedure. The only really

rude surprise is that little machine that shoots air into your eye,

but the purpose of each procedure in an exam is, for most of us

laypeople, a mystery.

A regular eye exam isn’t a painful procedure. The only really rude surprise is that little machine that shoots air into your eye, but the purpose of each procedure in an exam is, for most of us laypeople, a mystery.

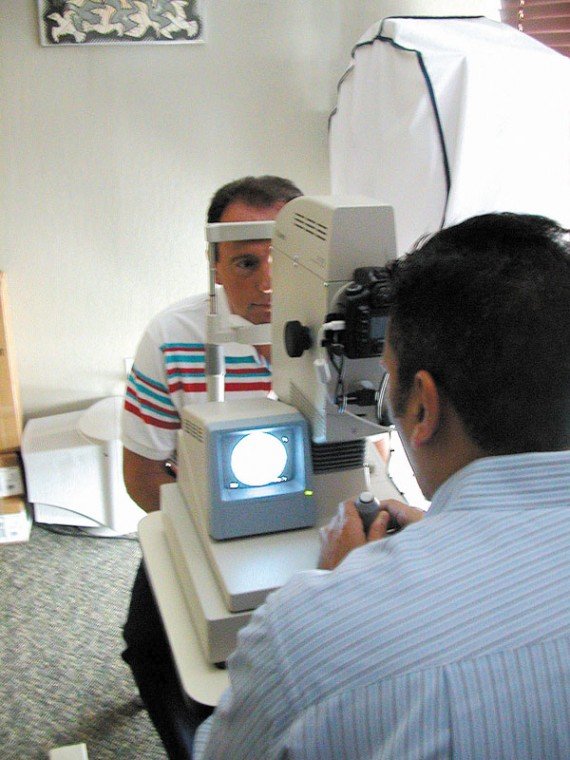

To guide us through the process, let’s introduce Dr. Paresh Patel and his patient, Dan Mitchell.

Mitchell sits in the exam chair, smoothing his red-and-blue striped polo shirt. His hands come to rest on his knees as Patel asks him to read from a row of letters projected on the far wall.

“H R Y …”

The 54-year-old can’t complain about the results of the LASIK surgery he underwent three years ago, despite the fact that he did develop mild glare when driving at night.

It was a clearly explained complication of the surgery, and he has glasses to correct the issue.

The reason he’s sitting in Patel’s examination seat now is that he’s having trouble reading fine print, and he’s ready to have his eyes examined for reading glasses.

Patel holds up a small paddle to cover one of Mitchell’s eyes, carefully looking into the one that is still open while directing his patient to look straight ahead. He’s checking the balance of Mitchell’s eyes, making sure both point straight ahead rather than turning in, out, up or down.

He then picks up what looks like an oversized lollipop. It’s really a slit lamp, a handheld microscope that allows him to look at the tissues in the front part of the eye, checking for signs of cataracts, eye infections or allergic reactions. In Mitchell’s case, he examines the LASIK scars.

The slit lamp contains a small light, which allows Patel to see the back wall of the eye, where the ocular nerve, which sends the eye’s visual image back to the brain, meets our baby blues, our gorgeous greens or our breathtaking browns.

This process can be done with even more detail using a process known as opthalmoscopy. It’s a digital scan of the back of the retina, taken with a machine that combines a digital camera with a high-powered microscope.

The images it yields look more like modern art than what one would picture the inside of the eye to look like. The major blood vessels of this small structure are all visible, as is the large, cable-like optic nerve. To its left is a bright white dot, called the macula.

This is the portion of the eye where light rays focus, much like the precise overlap of color bulbs in an old-fashioned projection television. But beyond art, this scan can uncover plenty of issues that have no seeming connection to eye care.

The optical nerve that the doctor examines is a directly observable link to the brain, and changes in its size can signal the development not only of the eye disease glaucoma, but also the presence of brain issues like pituitary tumors, said Patel.

Minuscule dots that can appear in the photograph are duly noted and investigated, too. The small dots represent ruptures in the tiniest capillaries of the eye, and can alert doctors to uncontrolled diabetes or the progression of diabetes that was thought to be under control.

After all of this, Patel uses refraction to check Mitchell’s prescription. He’s been given a rough estimate of the patient’s level by a machine called an auto refractor, which measures the distance between a patient’s eyes as well as the curvature of their surface and the axis of their focus.

This was done during the pre-exam period, when optician Amber Vanetti performed a variety of preliminary tests on Mitchell’s eyes.

The auto-refractor simply required Mitchell to look into a viewfinder and focus on a picture of a house while the computer read the shape of his eye, said Vanetti. There was also the tenometry machine, also known as “that thing that shoots air in your eye,” which tests the pressure in the eye sort of like an ultra-fine tire gauge.

A fields test was next. It that asks patients to stare at a black square and click a remote each time he or she sees a squiggly line appear in peripheral vision.

Finally, a stereopsis test was used to measure how well both eyes see together by asking patients to pick which number in a strand appears to stand up from the page, said Vanetti.

Patel takes this information into consideration as he tests Mitchell’s eyes, determining the limits of the patient’s vision by asking him to read lines of text in a variety of sizes while looking through lenses with a variety of strengths.

Then, Patel must balance the readings he’s collected with information about the patient’s personal life.

In this case, Mitchell works at a desk during the week, but he also plays softball. His vision distance is doing well, so Patel prescribes him reading glasses for use when working on the computer.

He’ll set the lens’ strength to a focal point that ranges from normal reading distance to about an arm’s length away, allowing Mitchell to work at his desk without strain.

The resulting prescription would have been different if Mitchell had been, say, a jeweler who needed to focus on things that were up close, but he’ll soon be seeing clearly again, says Patel as he leads Mitchell out to the office’s frame section.

Picking the right pair of glasses

When you live with the need for prescription eye correction, picking the right frames can be just as important to you as getting the right prescription, but getting it right sometimes requires getting a bit of help. Opticians Amber Vanetti and Beverly Place, both of Visual Edge Optometric Group in Gilroy, offered up a few suggestions you just may want to take note of:

• The higher your prescription, the smaller your lens should be. This trick of the eye helps to distort your face less and makes those Coke-bottle lenses look a bit thinner. That, and it’ll take about half the weight off your face.

• Pick a lens type that works for your level of activity. Lenses come in all kinds of materials, from plastic to compressed glass and polycarbonate, a shatter-resistant, scratch-resistant plastic material.

• Order lenses with a UV coating to block out harmful ultraviolet rays or order Transitions lenses, which can go from clear to shaded depending on the light in a room or outside. Not protecting your eyes is like “going out for a day in the sun without sunblock,” said Place.

• To get the best shape and fit, choose a lens shape that does not mirror the shape of your face, but do try to get a lens whose upper edge is shaped in a manner similar to that of your eyebrow. The frame is wide enough if it looks as if the bows, or side arms, of the glasses stick straight out from the sides of your head, said Place.