For 30 years, during careers in engineering and computerized banking, through fatherhood and retirement and as a student and teacher at Gavilan Community College in Gilroy, Herb Spenner lived with a singular, droning dream.

Now, every chance he gets, he drives his bright red Mazda the 20-odd miles from his home in the Almaden Valley section of San Jose to a cavernous classroom hanger at the tiny, ground squirrel-plagued San Martin airport.

He’s finally building his dream—for himself, his family and friends.

And when he builds it, they will fly.

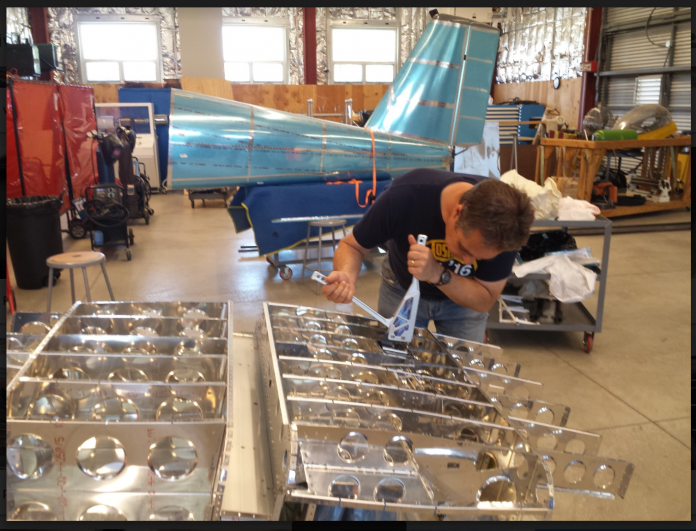

From a kit that arrives in big, raw wood boxes packed with gleaming sheets of thin aluminum, steel cables and maybe 15,000 rivets, Spenner is building an airplane.

When all is said and done, it will have consumed perhaps 1,000-plus hours of meticulous, exacting toil over two to three years of a lifetime.

And the total price tag will hover at an altitude of about $100,000.

Small price to pay to make a dream come true, is how Spenner, 59, looks at it now that summer vacation’s here and he can rivet and bolt pieces together unfettered by the demands of teaching aviation maintenance technology students at Gavilan Community College.

It’s an accidental job that took off after he retired from electrical engineering, stints owning a company and consulting and tending to complex software that banks use to transfer billions of dollars with the push of a button.

Yes, he concedes, he grounded his Wright Brothers dream during a time-sapping career of start-ups and downs. And anyway, his wife and their son and daughter were his priorities; the cost of a languishing dream was out of the question with mouths to feed and college tuitions to pay.

But now, he’s building his flying machine.

Ironically, Spenner’s working a short hop from where aviation pioneer Robert Fowler did the same thing shortly after the Wright Brothers went airborne for 12 seconds over a distance of 120 feet on Dec. 17, 1903, near Kitty Hawk, NC.

Spenner was unaware of Fowler, although knew of another, unrelated Fowler who gave his name to a wing invention, the Fowler Flap.

Robert Fowler was a Gilroy bicycle mechanic when he caught the flying flu and built and tested his first Wright-like flying machine off the gentle slopes of Gilroy’s eastern foothills along Crews Road near his home, which still stands.

A photo of Fowler hangs in a special pioneers’ room at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.

Taking off from Golden Gate Field in San Francisco and landing in Florida, Fowler was the first to fly across the United States from West to East coasts, It was a weeks-long trip in 1911 at about 40 mph and 100-ft. altitudes, with many harrowing up and downs.

The four-man competition sponsored by Hearst Newspapers did not have a winner; no pilot finished in the requisite number of days.

Fowler also partnered with aviation legend Glenn Curtiss, considered the founder of the aviation industry, to manufacture planes on Long Island, New York.

A competitor of the Wright brothers, Fowler’s firm was located near the spot where Charles Lindbergh would take off on May 20, 1927 from Roosevelt Field for history’s first trans-Atlantic flight, landing in Paris, France.

The Gilroy aviator at one point was tried as a spy by the US government because he and a passenger flew over and photographed the Panama Canal while it was under construction. He was exonerated.

Although unacknowledged in Gilroy except for some materials at the city museum, a bust of Fowler stands in the San Jose International Airport. His papers and a pair of goggles were donated to the Hiller Aviation Museum in San Carlos by his daughter in the 1990s.

When the Hiller opened in the late 90s, it had the aviator’s famous Fowler-Gage biplane, according to Jeffery Bass, the museum’s President and CEO.

The plane was owned at the time by the Smithsonian which has since brought it to Washington, DC, he said.

Fowler would be dazzled by Spenner’s flying machine and its cost.

It’s called an RV-12, what Spenner refers to as a Miata-like craft with a bubble cockpit and the two-seater configuration of the sleek sports car.

The Federal Aviation Administration categorizes the aircraft as “experimental”. That means it can be built for educational purposes and flown without all the government red tape that applies to more complex aircraft.

The letters RV stand for its innovator, Richard VanGrunsven, who founded Vans Aircraft, Inc., near Aurora, Oregon in 1972. The firm has shipped more than 8,000 kits to 60 countries, according to its website, vansaircraft.com.

Spenner’s two-seater, side-by-side kit is the firm’s most popular and comes with a price tag of $66,685, he says.

Special tools, an expensive paint job, a nearly $27,000 Rotex piston engine, a solid state, computerized instrument display, a final inspection by an FAA certified pro and sundry other necessities will easily add another $30K-plus to the cost, Spenner says.

And while he is building in the college’s workshop/hanger cum classroom, he’s doing it all at his own expense with tools, including a drill press and hand-operated riveters, lugged from home.

The project began in Spenner’s two-car garage, with parts splayed out all over a nearby room and pool table.

But when he told Gavilan President Kathleen Rose about his project during the grand opening of the school’s airport facility in September 2016, she encouraged him to bring the project to Gavilan.

He did. It’s now part of the curriculum of the Air Frame and Powerplant classes that are graduating licensed or certified aviation technicians as fast as the industry can hire them, according to Spenner.

Like many of his students, Spenner’s fascination with aviation began early.

After helping a friend restore a rare 1946 Ercoupe plane he realized he was smitten with the bug.

“Since then, I’ve always wanted to build an airplane,” he says.

He earned a pilot’s license, graduated from Purdue University in Electrical Engineering, made avionics for the military for a while and visited nearby Oshkosh, WI, known as a mecca of aviation fans, as often as he could while living in Milwaukee.

Fast forward, and years of the corporate life got to be too much of a grind.

“I was spending more time in the boardroom than with engineers; that was enough,” he says.

So, Spenner retired 12 years ago and not long after signed up for the aviation tech classes at Gavilan to learn what he needed to know to finally build his flying machine – with two big conditions: the aircraft would have to have more than one seat and two of them had to be side-by-side.

“I don’t like to fly alone,” he explains. “Flying is social, I like to experience it with others.”

And that’s when this plan began again to go into a tailspin.

When Gavilan realized he was a wiz in math, he was asked to help fellow students who were struggling – so he coached them while attending classes, too.

He was graduated in 2009 from the two-year Gavilan program and was hired to teach part time in the department.

That turned quite suddenly into a full time job when his instructor had a family tragedy and had to step down.

“He just called me up and asked me if I could teach his classes,” Spenner says.

He took over the classes, and then spent the next couple of years redesigning the entire curriculum – all of which took him further away from fulfilling his dream.

“The plane got put on hold,” he says.

Finally, last year, he ordered the kit. And by the time he and his daughter returned from an inspiring visit to Oshkosh, the raw wood boxes had begun to show up at his doorstep. Soon after, the garage was cleared of autos and the pool table went silent.

For an electrical engineer who has learned about aviation maintenance and mechanics, building an airplane is not a typical bucket list item, according to Spenner.

He calls it an “Almost Mt. Everest-like” undertaking for someone with his background.

No problem; Herb Spenner has begun his ascent.