MORGAN HILL

– Grass Valley Studio spills over 1.8 acres of this south Santa

Clara Valley city. There are fields and flowers with a sculpture

garden, including a ceramic piece called

”

Foot Soldier,

”

which is a reflection on World War II, and a figure called

”

Yellow Presence,

”

which is so named simply because it is yellow.

MORGAN HILL – Grass Valley Studio spills over 1.8 acres of this south Santa Clara Valley city. There are fields and flowers with a sculpture garden, including a ceramic piece called “Foot Soldier,” which is a reflection on World War II, and a figure called “Yellow Presence,” which is so named simply because it is yellow.

Abstract artist Bob Freimark constructed it of PVC tubing.

“Nobody else was using it,” he said. “It captures space with line, and not with solid form.”

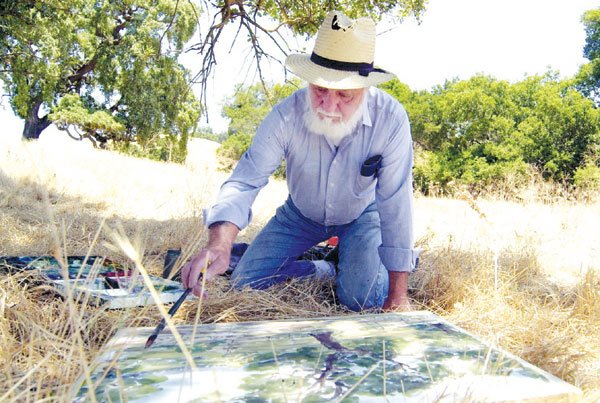

Freimark, an award-winning artist and documentary filmmaker, turned the rural space into an art studio nearly 40 years ago, and has been creating in it ever since.

At 82, he is a world traveler, determined to continue pursuing the arts he learned at school.

That determination has led him to numerous adventures and experiences in his lifetime. Freimark said he was the first U.S. painter to visit and exhibit in communist-influenced Cuba and the first to gain access to the former Czechoslovakia when it was behind the Iron Curtain.

Freimark’s travels take him all over the world, but he calls Morgan Hill, where he has lived with his wife Lil since 1964, home.

In the early 1960s, Freimark was the artist-in-residence at the Des Moines Art Center in Iowa. But, “I’d wanted to be part of a livelier art scene,” he said, so they moved to Los Angeles. The couple had concerns about the drug scene, however, and didn’t want to raise their daughter Christine there.

“We wanted to go someplace else, and then I got a job teaching at San Jose State University,” he said.

So, drawn by the prospect of farming, they moved to Morgan Hill, where they raised Ancona chickens, ducks, and geese and Freimark taught.

Freimark retired from San Jose State 15 years ago, but he hasn’t slowed down. He still makes art and documentary films, spotlighting activists and dissidents.

“Documentary is history, not artificial setup, and it teaches,” he said.

His 2003 film, “Los Desaparecidos: The Disappeared Ones,” documents the murders of some 30,000 in the 1960s and 70s by the Argentina military junta under General Videla. The film won “Best in Show” at the Accolade Competition in 2004 and a Freedom Award in 2003.

Freimark also wants to add more footage to his 35-minute film about a group of California Latino activists. The film, called “Political Posters in California: The Royal Chicano Air Force,” made its U.S. premiere in May in San Jose. The RCAF is a group that uses mural paintings, poster art production and other art to celebrate Chicano culture and fight for equal rights.

“Latinos are half of the West Coast,” Freimark said. “The RCAF flies beneath the radar, making posters, investigating government actions.”

Freimark will put his filmmaking skills to use in November as a juror of Morgan Hill’s Poppy Jasper Film Festival.

The artist not only documents other activists, he is something of one himself. A museum festival in Oregon that left out Cuban artists prompted him to petition the U.S. Treasury Department for entrance to that country six years ago.

“I was infuriated,” he said. “We are starving in America for information. We don’t know anything about Cuban artists. Our government has made it impossible for an artists’ exchange.”

He arranged immediately to visit Havana to find Cuban artists. He made his film, “Arte Cubano,” attended a party with Fidel Castro – whom Freimark said is very voluble and a ladies’ man – and even saw musicians of the Buena Vista Social Club standing on a corner.

Continuing his work with Cuban artists, Freimark plans to travel on a cultural exchange this summer to Vancouver, British Columbia, where Cuban artists are allowed, to show the film and attend a workshop.

Freimark said his enthusiasm for art began, oddly enough, when he was 5 years old, and Charles Lindbergh flew over his house in Doster, Mich., in 1927. After that, he and his dad flew in a Waco biplane at the county fair, and all his friends at school wanted him to draw them pictures of the experience.

His dad even signed him up for a mail-order art course. “It was a terrible waste of time,” Freimark said, “but Dad was interested.”

Freimark’s career was further nurtured when he served in the U.S. Navy in the 1940s and fellow soldiers asked him to draw pictures of their sweethearts from photos. When the war ended, Freimark went to the University of Toledo on the GI Bill.

And with a master’s degree in fine arts in 1951 from Michigan’s Cranbrook Academy of Art, Freimark sculpted, drew and painted as he farmed. His art won accolades, such as the Lambert Fund prize for his oil painting “Mexican Arena.”

As an art student more than 50 years ago, Freimark exhibited right alongside Pablo Picasso at the Chicago Art Institute.

“I didn’t meet Picasso, but I felt honored,” he said. “I didn’t even have the money to go to Chicago in those days.”

And in 1980, as an artist representing the United States, his tapestry titled “Olympic Flame” was exhibited at the Olympic Summer Games in Moscow.

But Freimark couldn’t attend the ceremonies, and never received his tapestry back.

The United States and some 60 other countries refused to participate to protest the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan the year before.

“Fortunately, the U.S.S.R. did not pull my tapestry and it was on display,” he said.

Freimark learned tapestry making at the Moravian Museum in the former Czechoslovakia, as the first U.S. artist permitted to visit the country when it was part of the Eastern Bloc.

After decades of new experiences and creating, Freimark doesn’t seem to be headed for rest any time soon.

In addition to the cultural exchange in Canada, he is working on watercolors for a display at the Morgan Hill Community and Cultural Center next year and is hoping a series of his paintings is accepted at the National Museum of the American Indian, scheduled to open Sept. 21 in Washington, D.C.

Propelled by a life-long passion for abstract art and film, Freimark likes to be surprised by his own work.

“I don’t plan where things are going until I finish,” he said. “I’m superstitious.”