Although 20 years have passed since the Loma Prieta earthquake,

the men and women at the heart of the city can still remember the

rush to ensure the safety of Gilroy’s 30,000 residents.

Although 20 years have passed since the Loma Prieta earthquake, the men and women at the heart of the city can still remember the rush to ensure the safety of Gilroy’s 30,000 residents.

Former city administrator Jay Baksa was at home when the earthquake rocked Gilroy, and he immediately knew it had been a big one.

“As I was leaving my house and driving into the city – I will never forget this – there was this dust, a haze over the town, like the whole town had been lifted up and dropped,” Baksa said.

He arrived at the city’s emergency operations center within five minutes, and soon other city employees streamed into the tiny space beneath the old Gilroy Police Department near Church and Seventh streets.

“When you get there, your adrenaline is moving pretty good,” Baksa said. “We were pretty well trained, having just gone through a major flood two years earlier. The training kicked in, and the adrenaline sort of slowed down.”

The first few hours in the room were filled with tension and confusion as the dozen or so workers, sitting shoulder to shoulder, collected initial reports from public works crews and monitored 911 calls.

“There were a lot of calls, a lot of damage. It was hard to tell what was significant at that point,” said then-city Planning Director Mike Dorn, whose job was to map areas with the highest concentration of damage. “There were a lot of false reports.”

Power was out throughout Gilroy overnight, and phone lines were also down. Baksa said the town went quiet.

“It was kind of eerie,” he said. “First of all, everything was pitch black.”

They watched Salinas and San Francisco television newscasts about the devastation to get a sense of what was happening beyond Gilroy.

The epicenter of the 6.9 earthquake was located nine miles northeast of Santa Cruz. While Gilroy was closer to fault line than Hollister, Oakland and San Francisco, it suffered less damage.

Among the worst catastrophes, a section of the Cypress Bay Bridge in Oakland collapsed, buildings tumbled down and fires ensued in San Francisco’s Marina District, and several structures crumbled in the Pacific Garden Mall in Santa Cruz.

“For the first couple of hours, we had a sense of being isolated,” Dorn said. “There was so much attention on what was happening in San Francisco and Oakland that we felt like we were on our own. We had to try to cope with our city and with our own staff.”

In Gilroy, firefighters chased down gas leaks during the night while public works crews repaired two leaking water mains on the city’s east side and a damaged water tank on the west.

“We had the police running around pretty ragged,” Dorn said.

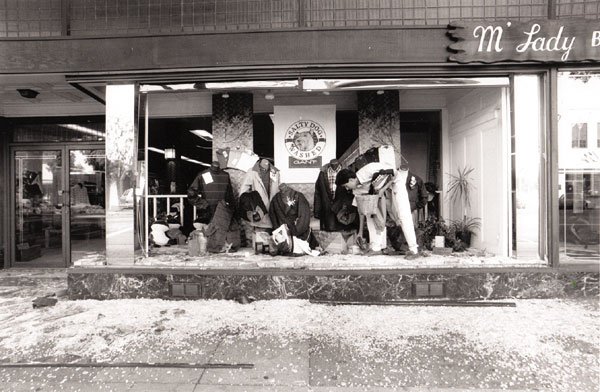

City building inspectors hurried to survey damage downtown, where many buildings were built with unstable, unreinforced masonry, and then combed the city responding to calls of damaged houses and buildings. Downtown, Old City Hall suffered severe damage.

“We had to prop it up with two-by-fours of lumber within the first 48 hours, or it would have collapsed,” Baksa said. “We had serious aftershocks that occurred for three to four weeks.”

Aftershocks between magnitudes of 1.0 and 5.4 were felt within one year of the quake. Gilroy spent the next four years using Federal Emergency Management Agency money to repair Old City Hall and to retrofit it so that it could withstand another major earthquake.

Given the fear and damage, Gilroyans showed real poise, Baksa said.

“It was an extraordinarily warm day that day,” he said. “People were out on their front lawns, sitting and talking. It was sort of a proud day for Gilroy. There weren’t the problems that occurred in other cities when you have a major disaster. People were pretty level-headed.”