Last year I read

”

A Year without Made in China

”

by journalist Sara Bongiorni. Troubled by the collection of

Christmas gifts under her tree, she decided to try living for a

whole year without buying any products made in China. Despite being

a bit repetitious, the book was an eye-opening expose of the vast

range of everyday products which come from Asia’s manufacturing

colossus (and the difficulty in finding replacements produced

elsewhere, especially in the USA).

Last year I read “A Year without Made in China” by journalist Sara Bongiorni. Troubled by the collection of Christmas gifts under her tree, she decided to try living for a whole year without buying any products made in China. Despite being a bit repetitious, the book was an eye-opening expose of the vast range of everyday products which come from Asia’s manufacturing colossus (and the difficulty in finding replacements produced elsewhere, especially in the USA).

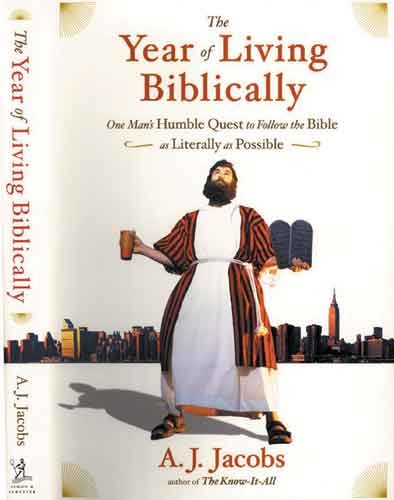

With this book still on my mind, I recently read a somewhat similar book by journalist and author A.J. Jacobs. “The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible” humorously recounts his attempt to follow the many teachings of the Bible as best he could for an entire year.

Jacobs grew up in a secular home in New York City. (“I am officially Jewish, but I’m Jewish in the same way that The Olive Garden is an Italian restaurant. Which is to say: not very.”)

One reason the author chose to write this book is because of the prevalence of biblical literalism in our society today. Millions of Americans say they take the Bible literally (at face value or according to its plain meaning). According to a 2005 Gallup poll, the number hovers near 33 percent; a “Newsweek” poll put it at 55 percent. A literal interpretation of the Bible … shapes American policies on the Middle East, homosexuality, stem cell research, education, abortion – right on down to rules about buying beer on Sunday.

But he was suspicious that most people, despite their statements to the contrary, actually pick and choose parts of the Bible that fit their agenda. Jacobs would be different. “I would peel away layers of interpretation and find the true Bible underneath … I’d discover what’s great and timeless in the Bible and what is outdated.”

The Bible contains well-known, universally-respected rules like the 10 Commandments, but also contains innumerable obscure rules like Leviticus 19:27, which admonishes men to keep the edges of their beards unshaven. This one results in “the most noticeable physical manifestation of (his) spiritual journey. ”

Clean-shaven before beginning the yearlong experiment, Jacobs “suffers for his beard” as it gets increasingly bushy:

Strangers pet it.

He’s given extra scrutiny at airport security.

Z.Z. Top is mentioned to him regularly.

He battled heat and itch.

Two little girls burst into tears upon seeing it.

During month three, Jacobs wrestled with Leviticus 20:27, which deals with capital punishment: “They shall be stoned with stones, their blood shall be upon them.” When a hostile old man he met by chance in a park admitted he was an “adulterer,” the author decided to administer the prescribed biblical punishment for this sin. His modern compromise was to stone him symbolically, throwing a small pebble against the septuagenarian’s chest.

Jacobs reflected, “Even though this was a stoning lite, barely fulfilling the letter of the law, I can’t deny it: It felt good to chuck a rock at this nasty old man … like I was getting vengeance on him. I wanted him to feel the pain he’d inflicted on others, even if that pain was a tap on the chest.”

“A Year of Living Biblically” narrates the author’s experiences as he spends eight months attempting to follow the Jewish Scriptures and five months concentrating on the New Testament. He supplemented his Bible-reading by consulting various experts, visited the Amish in Lancaster, PA, traveled to Israel and talked to a preacher who handles poisonous snakes as part of his congregation’s worship experience.

It would have been easy to write a book which satirized religion, making fun of believers and the teachings of this ancient book. But Jacobs didn’t write that book; the humor he finds in events does not denigrate the believers involved.

By the end of his experience, Jacobs realizes the value of religion and becomes what he calls “a reverent agnostic.” He states, “I now believe whether or not there’s a God, there is such a thing as sacredness. Life is sacred. The Sabbath can be a sacred day. Prayer can be a sacred ritual. There is something transcendent, beyond everyday.”