Long before the charreros frequented the section of downtown

Gilroy that some today call

”

Little Baja,

”

a bustling area from Seventh to Ninth streets along Monterey

Street was one of the Bay Area’s first Chinatowns.

Long before the charreros frequented the section of downtown Gilroy that some today call “Little Baja,” a bustling area from Seventh to Ninth streets along Monterey Street was one of the Bay Area’s first Chinatowns.

Today, there is nothing to tip off tourists – or residents – that this small, architecturally nondescript enclave of Gilroy was once this town’s epicenter. From opium gardens to gambling halls, Chinatown Gilroy could offer something to everyone, including mayors and city councilmen as well as movie stars passing through between Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area.

“I loved Chinatown,” said Masaru “Moose” Kunimura, a Japanese Gilroy native who once owned what is now the Cherry Blossom building. “People back then visited Chinatown because there was gambling – and it was exciting.”

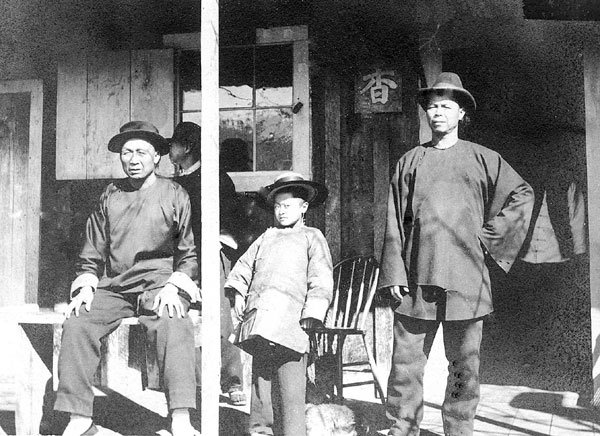

Lured by the prospect of finding gold, Chinese workers immigrated to the Bay Area in the mid 1800s. By the late 1800s, nearly 1,000 Chinese lived in Gilroy – roughly 700 more than today’s Chinese population, according to the 2000 U.S. Census.

History is sketchy on details about the Chinese men, and fewer women, who inhabited the area before the 1920s. However, anecdotal history remains alive and well for Gilroyans like Kunimura, 77, who was born and grew up in the then red-light district.

“People don’t realize how much activity there was in Chinatown before the war,” Kunimura said.

Chinese began to come to Gilroy in the 1860s to work the agricultural fields. One of the largest local employers of Chinese labor was James D. Culp, a tobacco grower from New York.

Culp patented a curing process in 1873 and established Consolidated Tobacco Company of Gilroy. He hand picked 900 Chinese workers to roll 1 million cigars a month.

By 1875, what is now known as the garlic capital could have easily been called the tobacco capital as more tobacco leaf was being manufactured in Gilroy than any other place in the United States.

Along Monterey Street one could find a pipe tobacco shop and cut-plug chewing tobacco factory. The world’s largest cigar factory was built on Monterey Street near the railroad yard.

According to historian Patricia Baldwin Escamilla, Gilroy tobacco was considered the finest in the world.

By 1870, three quarters of the agricultural work force at every level in California were Chinese. By this time, 3,536 Chinese women had emigrated to California, 61 percent (2,157) of whom were listed as prostitutes.

During this time, Gilroy’s Chinatown boomed. Chinese who did not work on farms, owned or worked at businesses along Monterey Street, which included laundries, restaurants, saloons, gambling houses, drug retreats and at least one brothel.

And then economics and politics reared their ugly heads.

The depression of the 1870s hit the South Valley hard and a variety of new laws made assimilation difficult for the Chinese.

At the time, Chinese constituted the largest racial group working in mines – 9,087 out of 36,339 by 1870 – but much of their wealth was lost to the Foreign Miners Tax, representing 25 to 50 percent of all state revenue. By 1882, federal law – the Chinese Exclusion Act – prohibited Chinese laborers from entering the United States.

By the 1900s, Japanese began to replace Chinese as agricultural workers and many of the Chinese laborers headed to the Central Valley for work, altering the ethnic landscape of Gilroy.

According to Kunimura, before World War II began Chinatown was no longer dominated by Chinese. Instead it was more like “Asia Town,” a mix of Chinese and Japanese peoples and businesses.

“From Seventh Street to Eighth Street everything was Oriental,” Kunimura recalled. ”Everything was built with wood.”

Those wood structures eventually fell prey to vandalism, fire, earthquake or age.

In the 1920s, outbreaks of violence by Asian gangs, called Tongs, would occur. Chinatown’s unofficial mayor at the time, Low Dan, was one business owner who refused to pay “protection money” to the Tongs. His general store was later burned to the ground. The damage can be seen in photographs at the Gilroy Museum today.

By the late 1920s and early 1930s, violence apparently became rarer in Chinatown.

Kunimura, whose uncle Junichi Tanaka bought what is now the Cherry Blossom building in 1928, recalls peaceful and lively times throughout his youth.

“In the Orient, the Japanese and Chinese fought like cats and dogs,” Kunimura recalled. “But in this town, everyone got along.”

And then, economics and politics reared an even uglier head, this time in the form of war.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese in Gilroy were interned. Kunimura went to a camp in Arizona, where he got his nickname “Moose,” because of his build compared to other Japanese young men. From the Arizona camp, he was later drafted into the military.

By the time Kunimura returned to Gilroy, Chinatown had been transformed once again. The tiny district became home to Chinese and Mexican immigrants. With the exception of the Kunimuras, none of the Japanese families who owned businesses in Chinatown returned to Gilroy.

“When I came back from the war there were four bars in Chinatown so I opened one up, too,” Kunimura said.

He also opened up a grocery store, Kunimura Market, which he kept for 12 years.

Sometime before 1960, Kunimura recalls, gambling in Gilroy became illegal. And soon after, bustling Chinatown became just another section of the downtown.

Although the lifestyle and the architecture of Gilroy’s Chinatown is long gone, artifacts remain.

John Tomasello, who now owns the Cherry Blossom building, has collected a number of them. In a section of Tomasello’s building, which he uses for his own storage, the longtime Gilroyan has lined his shelves with ceramic and mother of pearl vases, porcelain figurines and old bottles dating back to the late 1800s.

“I’m not a collector,” he said. ”I just noticed these things when we were grading for some concrete work I had done two years ago. I started digging, and then I dug a little deeper. I can go over there now and still find some interesting things.”

Tomasello figures that in the 1800s people often put their garbage in a pit to be burned or hauled away. Inevitably, some things would remain.

Tomasello has kept the artistic and the ordinary, both of which can captivate one’s imagination more than 100 years later. Among the more peculiar items: a bottle of “Dr. Kilmer’s Swamp Root Kidney Cure.” An 1883 bottle top from San Francisco Brew Co. also sits on Tomasello’s shelves.

“I never really thought about what I’d do with this stuff if I rented this place out,” Tomasello said. “I’d give it to the museum or to an antique store if they were interested.”