Detectives trying to snare suspects with telltale DNA face

month-long waits for evidence from the county’s crime lab

– a frustration that lab officials chalk up to mounting demand

for forensic tests.

Gilroy – Detectives trying to snare suspects with telltale DNA face month-long waits for evidence from the county’s crime lab – a frustration that lab officials chalk up to mounting demand for forensic tests.

“It’s not like you see on TV,” said Detective Sgt. Noel Provost. “They don’t do this in 45 minutes.”

After a rash of rapes by strangers this spring, Detectives Mitch Madruga and Michael Beebe expect to wait at least three weeks for lab results after submitting “rape kits” – swabs and clothing collected from survivors at the hospital. Two such exams have been completed after five attacks this spring. No one has been arrested for the crimes.

Meanwhile, Provost has watched attorneys repeatedly defer the murder trial of David Vincent Reyes, who confessed to killing his on-again, off-again girlfriend Franca Barsi in September, according to police. One of many reasons for the delay: Pending lab results. The case is now almost nine months old.

And Detective Frank Bozzo has held off on naming the cause of a Gilroy woman’s “suspicious death” in September, waiting on one last fingerprint test nearly nine months after the prints were submitted. Kathryn Ryle died of a gunshot wound to the chest, but detectives are unsure who pulled the trigger.

“The waits can hinder a case,” said Bozzo. “I’m sure the Ryle family wants closure on this case. I’d like to, too – but I’m not going to close the case until I have every bit of evidence back in my office.”

Other counties’ labs lag behind Santa Clara

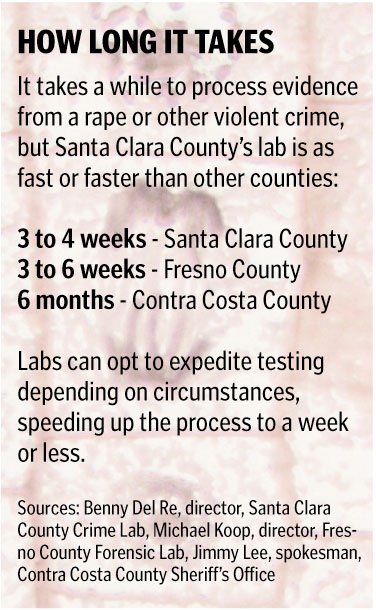

Still, Santa Clara County is quicker than most. With an average turnaround time 39 days for all kinds of forensic evidence, Santa Clara County’s lab is envied statewide, said lab director Benny Del Re.

“Most labs have thousands of cases backlogged,” said Del Re. “People come to us from other areas, because our turnaround times are so fast.”

The lab usually takes three or four weeks to process rape kits, said Del Re: In nearby Contra Costa county, rape kits typically take as long as six months to process, due to backlogs, said Jimmy Lee, spokesman for the Contra Costa Sheriff’s Office. Contra Costa’s lab has suffered a dire staffing shortage, and employs the same number of people it did in 1980, according to a recent civil grand jury report. In Fresno County, similar cases usually take between three and six weeks, said Michael Koop, director of the county’s forensic lab.

Rape evidence is particularly complex, Del Re explained. Often, technicians spend two or three days screening samples and documenting them in detail, noting their condition and checking if any substances can be tested. Samples can include clothing, bedding and swabs. Next, technicians extract the substances into a testable form, such as a single hair or a vial of fluid. The actual testing can take three or four days: Machines process the evidence, rendering results that must be interpreted by a technician. That can take time, too, said Del Re.

“You may be looking at a mixture of DNA – including the victim’s, the suspect or multiple suspects, maybe the victim’s partner as well,” said Del Re. “It’s intricate, and it needs to be sorted out.”

Because the stakes are high for defendants and victims, technicians subject their results to review by peers and supervisors. The fingerprints Bozzo is waiting on are being analyzed and verified by three different technicians, to guard against individual errors. If police lack suspects, DNA or fingerprints are filed to compare with a database; Bozzo has received belated matches on fingerprints, three years after a crime – sometimes after the statute of limitations has run out, he said.

Evidence can be expedited – sometimes

Despite the lags, technicians can speed up the process in some cases, working overtime and divvying up evidence among several technicians to get DNA processed fast.

“Is the suspect still outstanding, and are they going to victimize other people?” Lee asked hypothetically. “We’ve got a backlog, but if necessary, we can get it done in a week.”

Santa Clara County’s Del Re gave a similar example: In serial rape cases where the suspect is outstanding, he said, the lab has returned rape kits in three days. Gilroy detectives haven’t concluded whether the recent attacks are the work of one suspect or many, Sgt. Jim Gillio said Monday. Detectives have apparently not asked technicians to expedite the two rape kits; Madruga could not be reached Tuesday to comment.

Delays stem from a growing tide of evidence being sent to the lab, said Del Re. As new tests are developed, allowing police to gain more information from fingerprints and residues, lab technicians face increasing demands.

“In the last several years, with the growth of the DNA field … you’ve seen a steady increase in the amount of evidence,” said Koop. “The volume of evidence that gets processed from crime scenes is just amazing right now, and the technology and the staffing in the crime labs has to keep up with that.”

Del Re estimated that the lab’s caseload has increased 25 percent every year, for several years.

“Every year, we think we finally have a handle on it, and then demand jumps,” he said. Next May, the county is due to open a new crime lab in San Jose, but Del Re doesn’t expect processing times to drop when it does. “When we move in, we’ll have new capabilities – and that means new demands.”

Despite the wait, detectives are pleased by the work the lab does. Nationwide, Santa Clara County’s crime lab has been recognized as one of the best, and even won accolades in 2003 from the county’s frequently-critical Civil Grand Jury. Bozzo, who is in frequent contact with lab technicians, said he’s impressed by the amount of evidence they assess – and by how thoroughly they do so.

“I wish they could do it faster,” said Provost, “but I’d rather wait and get it done than have inconsistencies and errors. They’re very good at what they do.”