Visit Zeni’s Ethiopian restaurant in San Jose, and you’ll smell

it before you ever get inside

– pungently spicy flavors of red pepper, cumin, and coriander

that waft through the air near the yellow awning that marks the

spot.

Visit Zeni’s Ethiopian restaurant in San Jose, and you’ll smell it before you ever get inside – pungently spicy flavors of red pepper, cumin, and coriander that waft through the air near the yellow awning that marks the spot.

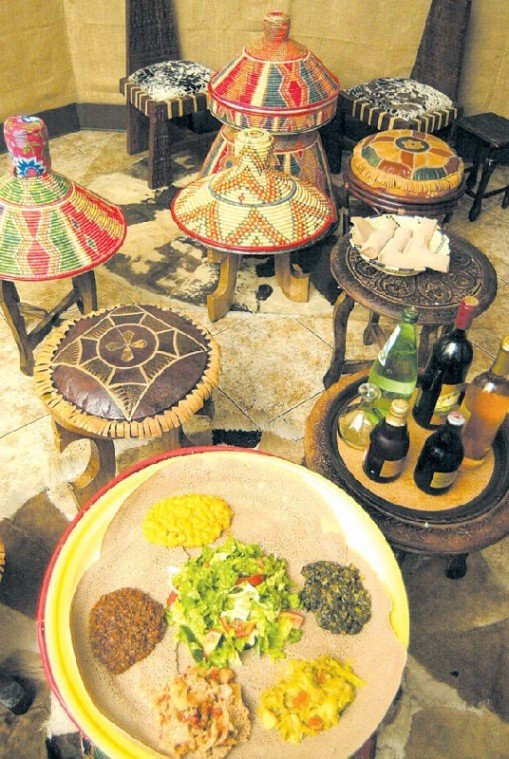

Here food is served on traditional bread known as Injera, made from one of the world’s smallest grains. At just about the size of a piece of sand, teff is the nation’s staple.

The grain is an extremely labor-intensive crop and does not respond to more modern farming techniques. The tiny buds must be threshed by hand, and teff grows best in

the cycles of natural farming – relying on torrential annual rains rather than irrigation to make crops grow. Ethiopia’s verti-sol (black soil) retains moisture for extended periods of time, allowing the teff to germinate on its own and be harvested, said Abe Feki, manager of Zeni. His wife Zeni Gebremariam serves as executive chef and owner of the restaurant.

Once transformed into fine powder, the grain is mixed with water and cooked over a hot clay round or, in the United States, a large circular hot plate.

It’s then used as the plate for a nightly meal, with various dishes arranged around its expanse like a wagon wheel.

Ethiopia, located on the horn of Africa, is also home to spicy sauces called wot. Served over vegetarian, beef, lamb or poultry dishes, the sauce contains a hearty dose of red pepper, cumin, cardamom and ginger as well as coriander and other spices.

Vegetarian dishes are a staple of the region, where as much as 85 percent of the population still lives in rural settings, farming in the ways their ancestors did for generations.

The largely vegetarian cuisine is as much a function of necessity as taste because meat in Ethiopia is consumed only on special occasions – four to five times per year for events like Easter and New Years, as well as weddings.

In large part, this is because livestock constitutes a family’s “cash, dairy supply and transportation,” said Feki.

In a family of seven, there may be only one to two actual breadwinners and any meal, no matter how meager, is considered precious, said Feki.

From scarcity, delicious cuisine was born. Lentils, yellow peas and collard greens cooked to perfection represent just some of the items that a typical family would be able to raise on their property.

The table itself is an expression of social value for Ethiopians, not just as the congregating place of the family, but a place of intense pride.

Traditional tables, called mossop, are actually woven by hand from dyed grasses. Their pattern is determined only by the craftswoman’s imagination.

Likewise, the stools that surround the table are carved from single blocks of wood – no nails, no screws, no seams – and are carved by the man of the family.

“If you share your meals together, you’ll have a very strong bond,” said Feki, discussing the cultural significance of the region’s communal eating practices. “People who eat together will be together often.

“Besides, in a third world country, the system doesn’t let you have freedom the way social security does. When you’re getting older, your social security is the number of kids you have.”

It is not uncommon for grandparents and aunts or uncles to live with a family if they are otherwise on their own, and in a large enough family the food will be split up into eating shifts by age.

At Zeni’s, a popular hangout among the local Ethiopian community, diners can also choose from Ethiopian honey wine, ales and other drinks to accompany their meal, as well as Ethiopian coffee.

In Ethiopia, coffee is a ceremonial event that begins with the roasting of fresh green coffee beans and ends with a cup of piping hot, extremely strong coffee.

Diners can observe the preparation of their beans and coffee for $25, but the order requires a one-hour warning, so it’s best to decide on before ordering a meal.

It’s best not to go to Zeni’s if you’re in a hurry, so come prepared to linger. If nothing else, it will give you an opportunity to view the cozy dining room filled with low stools and chairs and the walls festooned with Ethiopian art reflective of their society’s strict Orthodox Christian religion as well as scenes from around the country.

Entrees at Zeni’s range from $6 to $11.50 a plate, with the vegetarian meal, enough to feed two hungry people, going for just $9. There is also live instrumental music for free on Saturdays.

Zeni Restaurant is located at 1320 Saratoga Ave. in San Jose. For more information, call (408) 615-8282 or log onto www.ZeniRestaurant.com.