When asked how he acquired the intricate skill of segmented woodturning, Don Bianucci’s response echoes the Nike slogan.

“You just do it,” said the 75-year-old with a shrug of the shoulders, surveying the 18 bowls, vases and plates on display inside his residential showroom in rural Morgan Hill.

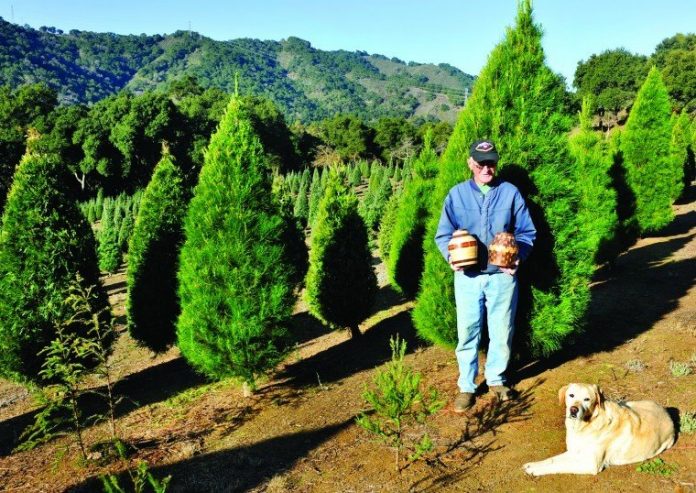

Bianucci’s constant companion, a whiskered yellow Labrador retriever named Molly who loves people almost as much as she loves stealing their food, sat sprawled at his feet.

A professional Christmas tree grower of 31 years who owns and operates Paradise Christmas Tree Farm at 15220 Yvonne Drive with his wife, Margaret, Bianucci is a local fixture whose wry sense of humor intermittently surfaces during an hour-long visit on a crisp Friday morning.

“No. It’s Mediterranean-Irish,” he cracks with a facetious grin, when asked if his name was Italian. “That’s what I tell people. And they look at me funny.”

Regarding his specialty hobby of segmented woodturning – a niche craft the weathered carpenter picked up less than two years ago – Bianucci says he has two reservations.

“My only two regrets are that I waited until 74 to do it, and that I don’t have time to work on it that much,” said the self-professed “country boy,” strolling through the horse barn he transformed into a workshop.

After getting rid of the family horses in 1972, the father of four, one of whom is deceased, admitted he was glad to see the large animals go.

“Dad had to do all the mucking and feeding,” he said, “while the kids did the riding.”

The large, airy space now belongs to Bianucci and his canine compadre Molly, who occasionally sidetracks her master from daily projects with an obligatory game of rope tug-o-war.

When he’s not tending to a verdant grove of several hundred Douglas fir, Monterey pine, Scotch pine, coastal redwood and incense cedar trees growing on the property in front of his home, the Morgan Hill resident of 42 years spends coveted spots of free time creating lathe-turned wooden bowls, plates, cookie jars and dry flower vases.

The process involves measuring and cutting small wood shapes, gluing them together to form a decorative pattern and smoothing the texture on a lathe that spins 900 rotations per minute. In the case of a dry flower vase, for example, the individual segments are assembled in a patterned design, then attached to the base and lip of the vase to form a complete piece.

The number of segments in Bianucci’s creations span from 150 to 300; the ranges of medium including sycamore, maple, black walnut, ash, poplar, Tennessee cedar, red cedar, red oak, olive and mulberry. Some of the wood comes directly from Paradise Farm, while the rest is purchased from stores, or obtained from friends and neighbors.

Picking up a wood beam and slicing through it like butter with a table saw miter gauge, Bianucci held up a small triangle with 15-degree angles.

“The cuttings have to be dead-on,” he explained. “There’s no room for error.”

The finished products are as smooth as marble; detailed to the finest degree with rings of ornate triangles, rectangles and wood segments that contrast in color from deep red to earthy chocolate. Aesthetic laminated bowls stand out with contrasting stripes of black walnut, red oak and maple. One segmented plate has a sun branching out from the middle, while a cookie jar made with red oak flaunts a design reminiscent of the zig-zaggy pattern on Charlie Brown’s T-shirt.

Knowing Bianucci has been at his newfound hobby for only a year and a half makes his gallery-worthy work all the more impressive.

As for the amount of time he pours into each project, Bianucci is at a loss.

“Everyone asks me that question,” he said, hands in jacket pockets. “I don’t keep track of the hours. It’s more than I’d care to admit.”

As he tries to determine which items are the most painstaking, the answer is equally broad as Bianucci concludes, “They’re all difficult.”

Which is why Margaret, 75, isn’t allowed to use her husband’s lathe-turned plates or bowls in the kitchen.

“I won’t let her,” Bianucci chuckled. “They’re for sale.”

His carpentry savvy took flight in the ’50s at Campbell High School, where woodshop instructor and mentor Bob Culp selected a young Bianucci to assist with the construction of a house. Though continuing on to an 18-year career working for General Electric, Bianucci’s preference for working with his hands came full circle later in life.

“I was pushing a lot of paper,” he said, of his first career. “And I hated it.”

The Bianuccis purchased their property in 1969 on the outskirts of Morgan Hill in pastoral Paradise Valley, where the previous owners planted walnut trees. Bianucci eventually left GE, had a stint building spec homes and later shifted his line of work to custom cabinetry in 1980.

The couple started their Christmas tree farm that same year.

The vocation sounds picturesque, although Bianucci underscores a shortage of holidays meriting the purchase of a Christmas tree. The industry veteran of three decades witnessed a number of tree farms come and go in a business that had initial promise, but dried up as larger competitors saturated the market, Bianucci said.

Turning and walking back toward the showroom, he added, “But I’m too stubborn to quit.”

Albeit, there’s nowhere else he would rather be living.

While Margaret hails from San Francisco, Bianucci, maintains “I would wither and die” in a big city.

After growing up near a creek in rural Campbell, Bianucci’s Morgan Hill home – situated adjacent to the shade-covered Llagas creek on Yvonne Drive near the 1895 Machado School House – is an uncanny paradigm of his childhood.

Recalling when he bought the property 42 years ago, Bianucci said he loves it now the same as he did then.

He continues to network and hone his craft; sharing and learning tricks of the trade from a small group of turners, carvers and furniture makers who comprise a monthly group called the South Valley Wood Workers.

In addition to the antique showroom at Paradise Farm, a number of Bianucci’s pieces were recently put on his farm’s website for viewing. Depending on the item, asking prices range from $35 to $350.

Out of 25 finished pieces, Bianucci has sold about half a dozen.

“I probably should find a better outlet for them,” he agreed, surveying the rustic antique room.

Bianucci insists, however, “I’m not doing it for the money. To me, to have somebody buy one of my pieces and thoroughly enjoy it – that makes my day.”