Q:

How did the South Valley town of New Idria play an important

part in helping save the environment?

Q:

How did the South Valley town of New Idria play an important part in helping save the environment?

A:

Today, New Idria is known for its negative impact on the environment due to the seeping of toxic mercury into the nearby creeks. But technology was once developed there that greatly benefitted Mother Nature.

Set in a canyon deep in the unincorporated south-eastern region of San Benito County, New Idria is now a virtual ghost town with only a few inhabitants. But in its heyday, it was one of California’s most important sources of cinnabar ore which mercury (also known as “quicksilver”) could be processed out of.

The New Idria Mining Company started mining the ore in 1854 and continued as a commercial enterprise until 1974. Nine decades ago, in an effort to modernize the operations, New Idria made history by serving as the test-bed for a new type of furnace that would dramatically revolutionize technology for ore processing around the world.

The United States in 1917 needed a significant amount of mercury as a key component of its munitions for fighting in Europe. At that time, New Idria’s mine superintendent and engineer Henry Gould noted that rotary kilns had been used for coal-fired cement production. He decided to experiment with these kilns for processing mercury at New Idria.

Gould used 5-foot rolled 1-inch iron plates riveted together to form a horizontal tube kiln measuring 5-foot in diameter by 56-foot long. An oil-fueled furnace heated the cinnabar ore placed into this experimental kiln that continuously rotated when powered by electric gears.

Gould’s innovative rotary kiln design was fully operational by March 1918. It proved far more efficient in reducing the cinnabar ore into mercury than past kiln processing that did not rotate. It thus increased the mining company’s profits considerably and helped supply the U.S. military with enough mercury to win World War I.

The Gould Rotary Furnace was also used worldwide in pulp and paper drying and waste disposal. Its energy efficiency significantly helped save the natural environment by producing far less pollution than previous kiln furnace technologies.

Q:

What’s the difference between the Costanoan and Ohlone Indian tribes in the South Valley region?

A:

The difference is one of semantics. Both words describe the same people.

When the Spanish came to our region of California, they encountered the indigenous population that had made their home here for many centuries. Because they lived next to or only a few miles from the Pacific Ocean, the European explorers called the inhabitants costeños, which means “coast-dwellers.” When the Americans came, the word evolved to the latinized “Costanoan.”

The name Ohlone is said to be the Indian’s original word for “the people.” It came to describe a group of about 50 individual tribes that lived around the San Francisco Bay and as far south as the Big Sur region. Among these tribes were the Mutsun Ohlone who made their home in the region of what’s now Watsonville Road, Uvas Canyon and Morgan Hill. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, the Spanish forced them from their tribal land and relocated them to the Mission San Juan Bautista. Many Ohlone Indians still live in the South Valley region, the home of their ancestors.

Q:

Why was Gilroy Hot Springs such a happening place?

A:

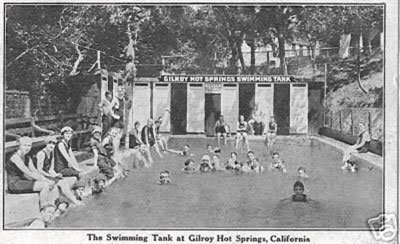

Located in a canyon of the Diablo Mountains about 10 miles east of Gilroy, the hot springs resort became a favorite get-away for Victorian vacationers in the 19th century. Heated by subterranean geological sources, water temperatures from the springs varied between 99 and 111 degrees Fahrenheit. The high sulfur content was believed to have healing and rejuvenating powers.

Set on 160 rugged acres, the resort was praised by one report in 1873 for having “the finest springs in the state.” A three-story wooden hotel was built at the site in 1874 and a series of guest cabins provided comfy amenities in a natural setting.

The resort peaked in popularity in the Roaring 1920s when it was a place for non-stop partying. During this decade, visitors enjoyed bootleg alcohol and slot machines. Thursday nights were popular for poker games. Saturday nights provided a band playing dance music. And, locals who remember those days say inebriated members of the Flapper generation often partook of late night skinny-dipping in the resort’s hot-water swimming pools.

The resort during the 1920s grew even more popular as automobiles made it more accessible. But with the coming of the Great Depression in 1929, Gilroy Hot Springs in the 1930s went into a steady decline with the public.