MORGAN HILL

– Olin Corp. officials are scrambling to evaluate clean-up

methods for the toxin perchlorate, which has bedeviled South Valley

residents for 10 weeks now.

MORGAN HILL – Olin Corp. officials are scrambling to evaluate clean-up methods for the toxin perchlorate, which has bedeviled South Valley residents for 10 weeks now.

Olin, which has assumed responsibility for the contamination, has until Monday to present its plan to the state Regional Water Quality Control Board for cleaning up the groundwater and the contaminated soil at the plant site. And it has until the end of the year to offer a plan for alleviating the problem in perchlorate-tainted wells.

Rick McClure, Olin’s project manager for the South Valley contamination, said Olin likely will not be able to meet Monday’s clean-up plan deadline.

“I don’t think we can comply fully with the letter (the March 31 deadline from the regional water board),” he said, until the many methods of perchlorate removal have been evaluated.

“Once we understand the geology, the ground water flow, where it is and which technology can work, then we can combine those things and commit to a plan,” McClure said. “It may be that a multitude of remedial technologies can be applied.”

McClure estimated that it might take 10 to 20 years to clean the water, although Kevin Mayer, regional perchlorate coordinator for the federal Environmental Protection Agency, said it might take 30 or 40 years.

McClure also declined to speculate on the ultimate cost.

“It’s a little early to speculate which method Olin will choose,” McClure said this week. He said there is more work to be done before they understand the size of the situation.

McClure said Olin is reviewing many technologies to find the one – or ones – that will work best for the water and residents in the affected South Valley.

McClure added that his only job is the South Valley project, the first time Olin has assigned a manager to only one project.

The regional water board based in San Luis Obispo will have to approve any clean-up plan.

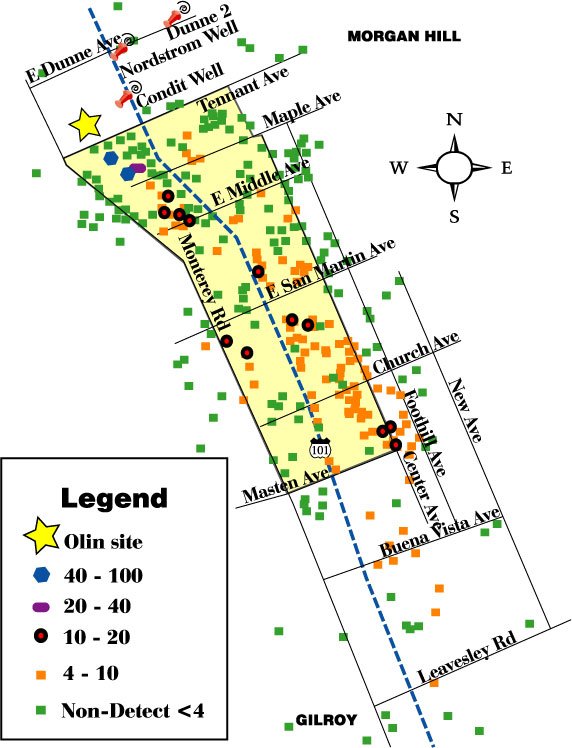

Since mid-January when the contamination was discovered, Olin and the Santa Clara Valley Water District, under supervision by the regional water board, have been testing wells to see how far the chemical has traveled from its origins at Tennant and Railroad avenues in Morgan Hill. Contamination has been found in well water just north of Gilroy.

“We’re still trying to get our arms around where it is,” said McClure.

Olin Corp. and Standard Fusee Corp. manufactured highway safety flares on the Tennant Avenue site between 1955 and 1996. During that time perchlorate was washed from mixing equipment and dumped into a holding pond on the site. The chemical, over the years, leached down through the ground into the aquifer. At the time, the practice was common and entirely legal though environmentalists have said it was “unwise.”

Thyroid problems possible

Perchlorate in the diet can cause thyroid malfunctions including thyroid cancers, retardation in severe cases and other health conditions. The chemical interferes with the body’s uptake of iodide, required for a properly functioning thyroid.

Olin has covered the site with plastic tarps – the buildings were removed in 1997 – to keep the winter’s rains from leaching more of the chemical into the underground water table. Soil clean-up methods are currently being evaluated.

By this week, of the 850 wells tested so far, 548 showed no measurable levels of perchlorate (nondetect or below 4 parts per billion); 286 have tested between 4.0 and 9.9; 14 tested between 10 and 19.9; two tested between 20 and 39.9 and two between 40 and 100.

The wells tested range from Tennant Avenue in Morgan Hill south to Leavesley Road in Gilroy though three Morgan Hill municipal wells, located north of the Olin site, recently tested above 4 ppb and were shut down. It was previously thought that, since the aquifer flowed south, southeast from the area of Bailey Road, wells north of Tennant would remain perchlorate free.

The City Council approved last week an expenditure of $640,000 to dig a new, emergency well to supply city users with water through the summer season. Some $710,000 was spent last year to dig a replacement for the Tennant well closed in April 2002. The bill, sent to Olin, is still under discussion between the city and the company, according to City Attorney Helene Leichter.

Though retests showed the contaminate levels on all three wells to have fallen below 4 ppb, the city has not put them back into use.

In Gilroy, the latest round of testing performed on that city’s wells found no detectable levels of perchlorate

Results from tests performed March 6 did not show perchlorate in the city’s eight municipal wells at or above 4 ppb, which is the reporting level established by the state’s Department of Health Services.

“They’ve all come back non-detect,” said Dan Aldridge, operations services supervisor in the city’s water department.

Gilroy upped the testing regimen on its eight municipal wells to at least once a month after perchlorate contamination was found to be widespread in private wells south of Morgan Hill.

There is no federally regulated level of safety for perchlorate though the California Department of Health Services must set a standard by Jan. 1, 2004. Currently the federal Environmental Protection Agency recommends 1 ppb though California is operating under the 2 and 6 ppb. Most laboratories that perform perchlorate testing cannot yet test reliably below 4 ppb.

Perchlorate contamination is treated, broadly speaking, in two ways: in situ (in place) and ex situ (removed from its natural place). With “ex situ” methods, water is pumped into an above-ground facility and treated there. Multiple wells would be drilled throughout the San Martin-Morgan Hill area and water pumped to a central treatment area. Currently recognized treatment procedures include a bioreactor method and one of ion exchange.

Different clean-up methods

The ion exchange method draws water into cells containing adsorbent material. Ion exchange resins are common but silica gels, activated carbon and molecular sieves are also used, according to the Calgon Carbon Corp. The perchlorate ions attach themselves to resin units and add chloride molecules; the altered chemical configuration renders the perchlorate harmless.

However, along with treated water, the process produces a brine solution which must be disposed of. Currently this is dumped, in the ocean or elsewhere or burned. Dumping will become illegal in California by 2006. Ion exchange is frequently used to treat water in Southern California which has a serious perchlorate problem because of the numerous defense facilities. The Santa Susanna area, site of a Rocketdyne field lab, has perchlorate levels of 1,600 ppb.

• Bioreactors, the other commonly used method, introduce aerobic microorganisms (bacteria that must have an oxygen source) into collected water. The bacteria eat the perchlorate. This method has been used for years to treat municipal and industrial wastewater. It, too, requires further treatment and disposal of its byproducts.

• Contaminated soil can be treated with bacteria, too. The soil is scooped up, mixed with clean soil and bacteria, and replaced, allowing the bacteria to remove the perchlorate.

• Phytoremediation uses a natural plant process and aerobic microorganisms to remove and/or degrade the contaminants in soil and in water.

In situ methods treat water underground without the need for above-ground treatment facilities.

• Anaerobic remediation eliminates the need for above-ground treatment plants. An anaerobe is a bacteria that lives in an oxygen–free environment. The bacteria is introduced to the underground water system where it feasts on perchlorate. This method has not been perfected.

• A permeable reactive barrier is a filtering system installed in the path of the perchlorate plume and, while it does not completely remove the chemical, has been found to reduce it.

In the meantime, many residents have decided not to wait and have joined class action lawsuits to force Olin to support medical studies of thyroid problems in the area and to mitigate the lowered property values. Other residents refuse to take part in the litigation, wanting Olin to concentrate its resources on the problem, not on the courts.

“It does carry weight,” McClure said, “when I tell the leadership there are people who don’t want to get involved with the lawsuits.”

“Olin has always been an environmentally responsive company,” McClure said, “and we’re going to continue that. We are committed to finding a solution that is acceptable. We’re going to do the right thing.”