GILROY

– Owners of wells contaminated with the dangerous perchlorate

chemical were told Saturday they may be able to use water from

their private wells sooner than the currently projected 30 to 50

years.

GILROY – Owners of wells contaminated with the dangerous perchlorate chemical were told Saturday they may be able to use water from their private wells sooner than the currently projected 30 to 50 years.

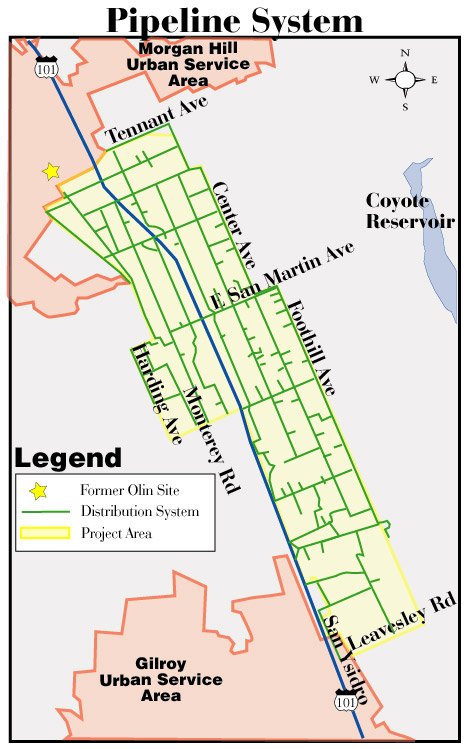

That news came out of a special seminar held Saturday by the Santa Clara Valley Water District to inform residents of what experts know about perchlorate and how to ultimately get rid of it. As of Friday, a total of 1,054 wells between Tennant Avenue in Morgan Hill and Leavesley Road in Gilroy have been sampled. Of those, 401 wells have tested positive for perchlorate.

Urged by its board of directors, water district engineers have collected six separate approaches to living with perchlorate-contaminanted water in the meantime. Those methods were revealed to 300 people who filled the Gavilan College student center and the grounds outside it Saturday.

Marc Lucca, senior project manager for the SCVWD’s imported water unit, presented the six alternatives. The six treatment methods vary on what they treat, how long they take to get up and running, and how much they cost.

Who would ultimately pay for any system is unknown, but panelist John Mijares of the Central Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board – the lead agency in the perchlorate battle – said the agency expects the Olin Corp. to assume financial responsibility.

The source of water for alternatives 1 through 4 and 6 is the contaminated groundwater in the Llagas sub-basin; all five would be installed in San Martin but are expandable to Morgan Hill and Gilroy.

• Alternative 1: Groundwater for domestic use only, treatment plant installed at the house or garage. Nitrates (a problem in rural areas) also are removed.

Owners retain control of wells and the equipment is commercially available from several sources as a direct purchase or on a contract basis.

Disadvantages are several: It does not satisfy agriculture/livestock demand and state Department of Health Services’ (DHS) approval of point-of-use devices are not yet available – some new technologies coming online will take a few months to certify for drinking water use. Certification is not required if a homeowner installs the system, but the homeowner may be required to perform routine maintenance.

Alternative 1 will take one to two years after the project is selected, and will cost $2 million in capital costs, plus annual operations and maintenance costs of $500,000. Equipment leasing would cost $800,000 annually.

• Alternative 2 is installed at the house and the well-head and would treat both domestic and agricultural water. The owner retains ownership of the well but the equipment is more complicated for the average homeowner to operate and maintain than a homeowner would normally undertake. Implementation time is one to two years and costs $13 million to $15 million, plus operations and maintenance costs of $1 million annually.

• Alternative 3: Point-of-use treatment for domestic use, plus use of recycled water for agricultural use. This alternative is considered to be a comprehensive solution for agricultural needs.

It has disadvantages, raising issues pertaining to impact of recycled water on the groundwater basin. The recycled water portion of the option has high capital and operations and maintenances costs. The recycled water portion requires a long time for implementation – three to five years – and would cost $135 million, plus annual operations and maintenance costs of $1 million.

• Alternative 4: Well-head treatment of groundwater for domestic and agricultural use. This method could be used on wells serving more than one home. Disadvantages include increased energy and maintenance costs and complicated equipment for the homeowner to manage. Alternative 4 would take one to two years to implement and cost $30 million, plus annual operations and maintenance costs of $11 million and $4 million to lease equipment annually.

This method is similar to what the water district board approved last week to treat groundwater, beginning at Morgan Hill’s city well at Tennant Avenue, located 250 feet south of the Olin Corp. perchlorate source.

• Alternative 6 treats and distributes groundwater for domestic and agricultural use, using a treatment plant, storage tank(s) and distribution system and would involve no change in management of the groundwater basin. This alternative is more easily expanded to treat other contaminants, for example nitrate, and removes contaminated groundwater and helps clean the groundwater basin.

This alternative has several disadvantages. It would preclude individual use of wells and require a longer time for planning, design, permitting and construction. Significant policy issues include chosing a retailer to provide the equipment and who would pay for what.

Time to implement is four to five years after selection with capital costs of $135 million, plus annual operations and maintenance costs of $2 million.

Alternative 5 uses source water from Anderson Reservoir (local rainfall and water imported from San Luis Reservoir).

• Alternative 5 includes a 7-million-gallon-per-day treatment plant, storage tank(s) and distribution system. It would involve some change in management of Anderson Reservoir but would preclude individual use of wells. It would prevent the use of the groundwater basin in the area, which is used as a significant source of water for during drought years.

A disadvantage is that imported water is subject to availability. For example during drought years and seasonal periods of time water quality becomes unacceptable for importation. It is also inconsistent with district’s long-term water supply management plans.

Alternative 5 would take a longer time to plan, design, permit and construct – four to five years and cost $150 million, plus annual operation and maintenance costs of $2 million.

The next step before a method is selected will be a discussion between the Central Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board, Olin Corp., the cities of Gilroy and Morgan Hill, the newly established Perchlorate Community Action Group, various regulatory agencies and others.