Joseph Fabiny strolls through a labyrinth of eggshell-colored

hallways lit with glum fluorescents, each exactly the same as the

last.

San Jose – Joseph Fabiny strolls through a labyrinth of eggshell-colored hallways lit with glum fluorescents, each exactly the same as the last.

“Are you lost yet?” he asks, chuckling.

By now, Fabiny knows his way around the Santa Clara County crime lab, an underground maze where criminalists decode a rebus of clues: A shoeprint. A spent bullet. A rim of sweat left on a discarded cap. For more than 20 years, scientists have tracked down perps with test tubes, microscopes and computers in the basement of an austere Berger Street building in San Jose, earning honors for their cutting-edge work even as more and more requests crowd their dim office.

“Talk to any lab administrator, and they want more space and more staff,” said Fabiny, the lab’s assistant director.

And next year, they finally will: The new county crime lab under construction on Hedding Street is due for completion next June, a four-story, 90,000-square-foot facility nearly quadruple the size of the existing lab. The Hedding Street digs will bring the computer forensics and toxicology units – now separate from the Berger Street building – under the same roof as the main lab, and give criminalists a much-needed breath of fresh air, said Fabiny.

Faced with staggering workloads, lab workers could use it. In 2006, the lab fielded 2,833 requests from 1,992 cases, including 63 cases from Gilroy, 5,477 narcotics requests (130 from Gilroy) and 15,467 toxicology requests (451 from Gilroy.) New technologies have granted them new powers, but have also weighed down criminalists with a slew of new requests. Fabiny calls it “a snowball effect.” Years ago, technicians needed a bloodstain the size of a dime – now, far less will suffice. Rapidly expanding databases allow analysts to link guns, blood and even tire-tracks to known suspects, sometimes reviving cases long left cold. By June 2007, the databases had turned up suspects in 53 murders, 130 rapes, 101 burglaries and nearly 200 other unsolved crimes, Fabiny said. Four or five new hits turn up every week.

“I wish they could do it faster, but I’d rather wait and get it done than have inconsistencies and errors,” said Gilroy Police Detective Noel Provost in an interview last month. ” They’re very good at what they do.”

Crimes can be foiled by unusual clues: Criminalist John Bourke displays a plaster cast of a sneaker-print, the telltale grooves lined with crime-scene gravel. Ninety percent of his cases involve Nikes, Bourke says. Thankfully, Nike employs someone to ship sneaker soles to crime labs, allowing Bourke to compare the print to a sneaker model – and to an FBI shoe database, he said.

It’s an unlikely specialty, Bourke admits, one that requires near-encyclopedic knowledge of Nike’s newest lines, as well as the latest styles from Goodyear and Firestone: Bourke also analyzes tire tracks. To single out the car that ferried a would-be murderer to a liquor store, Bourke recently preserved 11 feet of tire tracks, using 50 pounds of cement – “the same stuff they use for dental casts,” he said.

Down the hall, three firearms specialists compare the markings on cartridges and bullet casings, to check against the Integrated Ballistics Identification System database. For comparison, analysts test-fire guns into a water tank in a barrel-like room, from which they collect gunshot residue and bullets.

“It can provide powerful leads,” said Fabiny, a former firearms specialist. “Let’s say the officers pull someone over for DUI, and notice a gun under the car seat. We test-fire it, compare it – lo and behold, this gun was used in a homicide in 2003.”

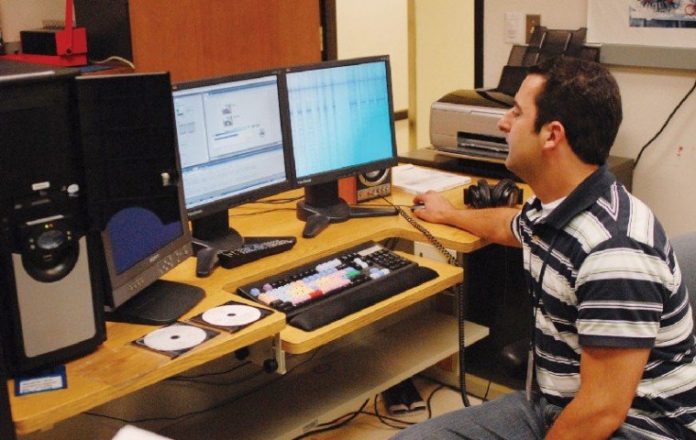

Other technicians test for drugs, enhance surveillance videos, and even examine whole cars. Excited by the possibilities, police, Sheriff’s deputies and the DA are submitting more cases to the lab, said director Benny Del Re, and that means more work for criminalists. Santa Clara County lab staff have a backlog of more than 300 guns to enter into the IBIS system – and that’s just in the gun department.

Lab directors are turning to robotics to cut down on simple but labor-intensive tasks such as pipetting fluids from tube to tube, but some delays won’t disappear until scientists move into the new lab, Fabiny explained. Work bays where criminalists array the evidence submitted on each case are often crowded, forcing scientists to wait hours until a bay is available. Sorting out the evidence can be time-consuming, as technicians extract evidence into testable form and assign bar codes to each and every sample.

“We’re juggling cases all the time,” Fabiny said. “It’s not like CSI, where you see four analysts committed to one case.”

Thankfully, the lab was spared from county budget cuts, which eliminated the DA’s Cold Case Unit and its Lifer program that assists victims of violent crime when the perpetrators are up for parole. But as the criminalists wait to move out of their bunker-like lab, expectations keep growing – and so are caseloads.