It’s my fault. And it’s also your fault. In fact, it’s the fault

of millions of folks living along much of coastal California. I’m

referring, of course, to the San Andreas Fault, the 800-mile

seismic powder-keg whose fault it was that the people and livestock

of the Parkfield area got jolted by a 6.0 earthquake last Tuesday

morning.

It’s my fault. And it’s also your fault. In fact, it’s the fault of millions of folks living along much of coastal California. I’m referring, of course, to the San Andreas Fault, the 800-mile seismic powder-keg whose fault it was that the people and livestock of the Parkfield area got jolted by a 6.0 earthquake last Tuesday morning.

I grew up in Hollister which one time – in search of an international identity – proclaimed itself the “Earthquake Capital of the World.” City officials and business leaders even discussed organizing an annual “Earthquake Festival” to celebrate the town’s dubious distinction. I still wonder how an earthquake festival might attract the crowds.

Festivals built around major natural disasters just don’t have quite the kind of sex appeal as, say, Gilroy’s famous Garlic Festival or Morgan Hill’s Mushroom Mardi Gras. What could you do at an Earthquake Festival – other than dance to rock-and-roll and drink shakes? So Hollister’s Chamber of Commerce eventually discarded the “Earthquake Capital” title.

Perhaps that’s a good thing. It frightened off too many potential home-buyers. Folks probably didn’t know how to explain to friends and relatives why they’d even consider purchasing a home in a town where Stanford and UC Berkeley geology students regularly come to gaze at cracked sidewalks.

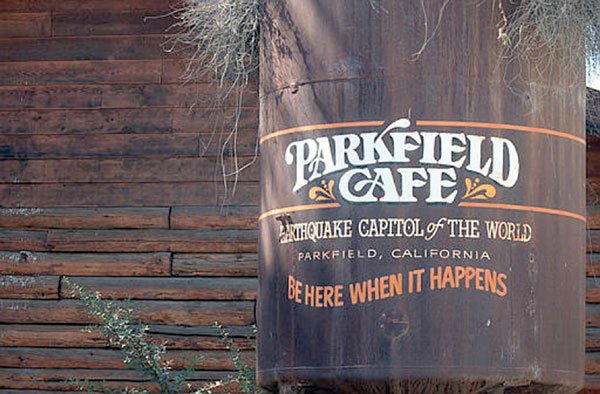

Wisely and rightfully, Hollister conceded the title of “Earthquake Capital” to Monterey County’s tiny Parkfield, a former quicksilver boom town with a population of 18.

One time, when I drove country roads back from Ventura to my house in Morgan Hill, I pulled in for a pitstop in Parkfield. The place was eerie. No one was in sight. The only sounds: the breeze lightly rustling leaves and distant ravens crawing. I felt like Rod Serling might saunter out of the Parkfield Cafe with cigarette in hand and, beaming his trade-mark creepy smile, inform TV viewers I had just entered the Twilight Zone.

The true Twilight Zone was far under my feet. Far scarier than a vintage TV show, the San Andreas fault, when you least suspect it, can suddenly let loose a terrifying quivering of the landscape.

But it’s not strange mystical forces that created this zone. It’s geology.

See, Earth’s North American plate shifts northwest about an inch or so a year as it rubs up tight against the Pacific plate. The pressure and stress build up as energy stored in the rocks miles under the surface.

About 10:15am Sept. 28, far beneath the tranquil cattle ranges of Parkfield, that pent-up energy came to a critical limit. The rocks couldn’t hold the stress any longer. The two plates abruptly shifted, allowing the land to release the massive amount of stored energy. The energy shot up to the surface. Earthquake! Suddenly, Parkfield’s fine citizens felt a whole lotta shakin’ goin’ on.

Occurring in a rural region, Tuesday’s quake certainly didn’t do as much damage as the great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 – or 1989’s Loma Prieta shock on the Bay Area. Some wine bottles broke and food spilled out of the local cafe’s cupboards. That’s about it for devastation.

But, in it’s own way, the 2004 Parkfield quake might prove to be just as significant in history as the famous 1906 San Francisco quake. Tuesday’s geological shudder might very well change how we view earthquakes.

For geologists, Parkfield is Seismic Central. The town has attracted a team of geologists constantly monitoring the exceptionally high flurry of earthquakes that occur there. They’ve been studying the area in a project called EarthScope – a 20-year, $200 million venture funded by the National Science Foundation. EarthScope’s aim is to understand quakes better and, possibly, develop a way to predict them. If scientists might one day be able to forecast a major quake’s probability fairly accurately, adequate warning can be given. Many lives can be saved.

As many as 17,500 people around the world die each year from earthquakes. That’s why the scientists at Parkfield are dedicated to learning as much as they can about them.

Researchers at Parkfield have recently drilled into the earth, boring a vertical cement shaft 0.9 miles deep into the San Andreas Fault to establish an underground observatory from which to analyze earth movement as closely as possible to its point of origin. Global position system arrays and seismic monitors track the movements of the earth during the abrupt jolts. Advanced computers take the data and turn it into graphic information giving geologists a more realistic picture of what happens when the two plates along the San Andreas Fault break loose.

It’s vital for communities in the South Valley that geologists study Parkfield. The San Andreas Fault waits like a sleeping dragon underground – under our very backyards. It is close to Morgan Hill, San Martin and Gilroy, goes through San Juan Bautista and lies just south of Hollister. The dragon WILL awaken again. We don’t know when. But we know it’s inevitable we’ll be hit by a major quake.

Despite what much of the country thinks about California’s earthquakes, if I had a choice of natural disasters, I’d prefer by far to endure an intense trembler than something like a powerful hurricane. In the United States, hurricanes historically result in far more deaths and property damage than earthquakes. The average number of deaths per year in the U.S. for hurricanes is 18. For earthquakes, it’s 6.

For geologists, Tuesday’s temblor was a surprise birthday party filled with lots of wonderful presents – gifts of geological data from Mother Nature.

It’s too early for geologists to make any significant conclusions from the deluge of data gathered last week in Parkfield. But if the information they learn saves thousands of lives by giving us a heads up for a major fault-line jolt, the benefits from last Tuesday’s quake might very well be … earthshaking.

If you’re interested in learning more about the EarthScope project, visit the Web site at www.earthscope.org.