In the middle of busy Hazel Hawkins Hospital there is a secret

oasis of solitude. Plush pillows and soothing hotel-like

accommodations invite the visitor to relax and nap a spell,

provided they don’t mind being attached to a bevy of electrodes and

watched remotely by a technician.

In the middle of busy Hazel Hawkins Hospital there is a secret oasis of solitude. Plush pillows and soothing hotel-like accommodations invite the visitor to relax and nap a spell, provided they don’t mind being attached to a bevy of electrodes and watched remotely by a technician.

This hospital’s sleep lab, still awaiting final approval from state inspectors, exists to diagnose and treat sleep disorders, particularly a stoppage of breathing known as sleep apnea.

“When you have apneas, the airway closes and your body isn’t getting oxygen,” said Michael Egbert, respiratory therapy manager at the hospital. “When your brain realizes it’s getting starved it says, ‘Wake up!’ You don’t become completely alert, but you wake up just enough to get the airway open. We call that an arousal, and it’s just enough of an arousal to disrupt your sleep patterns.”

The average apnea sufferer has between 300 and 500 of these episodes per night. If a doctor suspects problems based on a patient’s Epworth Sleepiness Scale (see box), that patient will likely be referred for further study.

Respiratory therapists measure disruptions in normal sleep by attaching electrodes all over a patient’s head. Two belt-style monitors are attached to the torso and chest, and more electrodes are adhered to the legs and eyelids to measure leg movement – a possible symptom of restless leg syndrome – and REM sleep.

In appropriate sleep patterns, a person rotates through REM, or Rapid Eye Movement, and non-REM sleep. REM periods are basically dream periods and they increase in duration throughout the night. The first stage of REM is only about 10 minutes, but by the last phase (generally around 5am) it will last nearly an hour.

“Through the course of the night, we’re looking to see what stage of sleep the patient is in,” said Egbert. “A technician in a separate room monitors what stage of sleep the patient is in and the recording is then looked at by a polysomnographer, a physician who specializes in sleep disorders.”

The polysomnographer will determine whether the patient has apnea, hypopnea (shallow breathing characterized by a 30 percent decrease in air flow) or another problem such as a hyperthyroid condition. In cases of both apnea and hypopnea, patients have two options: a breathing machine or a surgery with only a 50 percent chance of success.

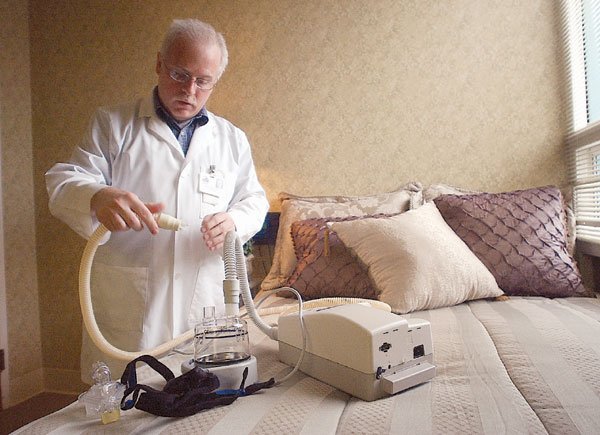

“A lot of people say they don’t want to sleep with a mask on every night, but the surgery is pretty expensive for something that’s not guaranteed to work,” said Egbert. “Most of the time we end up prescribing a CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Preserver), which is 100 percent effective when used properly.”

The CPAP acts as an airway splint, forcing a continuous supply of air into the back of a patient’s throat to maintain their breath passage overnight. A small mask fits over the nose, or sometimes a larger mask for mouth and nose is required, but compliance is an issue that Egbert and his staff run into frequently.

“Usually if something isn’t working it’s because the mask isn’t fitting properly,” said Egbert. “The effects are so phenomenal when it goes right that people come in here and say it’s a level of rest they’ve never experienced. Most of the people who come in are men, and a lot of them have no sex life anymore because they’re too tired. With the CPAP their energy is back – it saves their marriage.”

Men are twice as likely as women to suffer from apneas before the age of 50, but after menopause the gender gap equalizes, stabilizing at about 6 percent of the population according to the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. That number may not seem like much, but consider how many children in the United States have had an asthma attack this year: Just over five percent, according to the Centers for Disease Control. That deprivation is what a person with apnea is doing to the body unwittingly each night.

“People think it’s okay to snore,” said Egbert, “but about 50 percent of people who snore regularly actually have apnea. The impact of that on their health is awful – strokes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease. You can die in your sleep because your heart can get into an abnormal rhythm from this. It’s not about sleep apnea or snoring. It’s about life or death.”

The Hazel Hawkins sleep lab is located within the hospital, but is not open to the public yet because of a bureaucratic snafu. Its wing of the building is not zoned for outpatient services, but should meet final approval in the next 30 days. Sleep studies are currently conducted in the hospital itself, but the outpatient facility will be able to process as many as 25 new patients a month once opened. It’s already booked through December.

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale

Your level of alertness during the day may be reflecting what your body is doing at night, even if your spouse doesn’t seem to mind that snoring.

Rate your level of sleepiness with a “3” being an activity with a high chance of dozing and a “0” being no chance. A “1” is slight and a “2” is moderate.

1. Sitting and reading 1 2 3 4

2. Watching TV 1 2 3 4

3. Sitting inactive in a public place

(e.g. theater or meeting) 1 2 3 4

4. As a passenger in a car for an

hour without a break 1 2 3 4

5. Lying down to rest in the

afternoon when permissible 1 2 3 4

6. Sitting and talking with someone 1 2 3 4

7. Sitting quietly after a lunch

without alcohol 1 2 3 4

8. In a car, while stopped for a

few minutes in traffic 1 2 3 4

Tally your score and rate yourself

according to the following:

1-6 = Getting enough sleep

7-8 = Average level of fatigue

9+ = See your doctor immediately