While it may not be so easy for Betty Jane Sachara to read a

book or even see her way around her Gilroy home at times, it’s

obvious that she still dreams in full color and with a clarity some

may never experience.

In her 80th year, Sachara, a poet most of her life, is proof

that sometimes our best, most heartfelt work can come out of us on

the first try.

While it may not be so easy for Betty Jane Sachara to read a book or even see her way around her Gilroy home at times, it’s obvious that she still dreams in full color and with a clarity some may never experience.

In her 80th year, Sachara, a poet most of her life, is proof that sometimes our best, most heartfelt work can come out of us on the first try.

“I’m not a re-writer,” she said. “I don’t change it. Seldom do I change a thought.

“I guess you have to have a lot of confidence to write like I do. I lay in bed and think about it, and when I’m ready, I write it.”

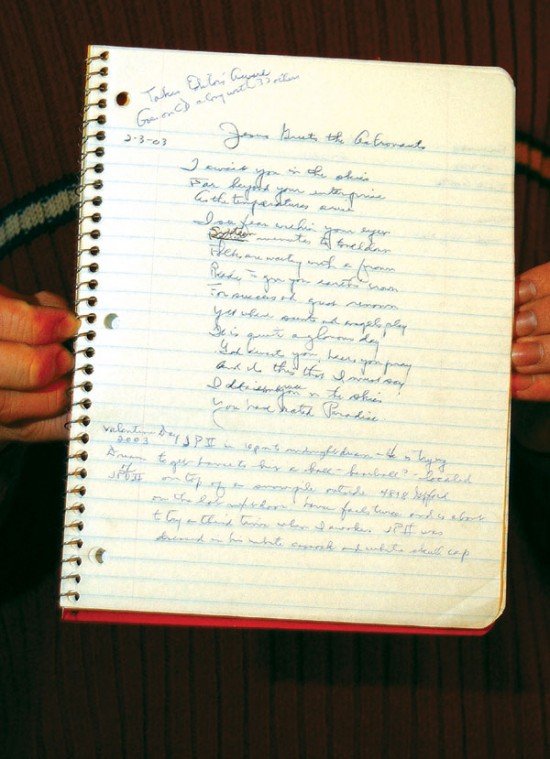

That’s exactly how she wrote “Jesus Greets the Astronauts,” a sonnet that was honored by International Library of Poetry with an Editor’s Choice Award in a recent competition.

“I think I changed one word, but that’s the usual way I do it,” she said.

The poem, which was a tribute to the seven astronauts that died in the Columbia space shuttle crash early last year, also will be included in the book “Eternal Portraits,” which has already sold out.

Although limited in her sight, especially in the day time, and she often struggles to move around with bad knees, Sachara’s activities may be slowed but she finds inspiration to create when the sun goes down and her vision returns to her.

“My time of writing is in the night,” she said. “That’s the only time of day that I can see.

Suffering from glaucoma, Sachara can’t tolerate sunlight, keeping mostly to her home with limited lighting during the day.

“It’s the tragedy of my life, losing my vision,” she said.

However, she finds she is able to go back to what makes her happiest, reading and writing at night.

“I can sit the and write a letter without glasses in the middle of the night,” she said.

Sachara has been a writer her whole life, and she has always been able to collect her thoughts in an amazing way. Once her pen hits paper, she rarely stops and rarely changes anything.

“I think I’ve written around 1,000 sonnets, and 10 percent received recognition,” she said.

However, that recognition doesn’t appear in the form of money – the most Sachara ever received for one of her award-winning poems was $200 for a sonnet on artist Ansel Adams.

“Poets are not well-paid,”she admitted. “But I keep filling my notebook whenever I feel strongly enough about something. The muse doesn’t speak to me as often. … I don’t write that much these days.”

Still, a large box in the Sachara’s home is filled with notebooks loaded with her verse, and when she saw the news about the tragedy the astronauts endured upon re-entry from a mission aboard the Columbia, inspiration struck the devout Roman Catholic.

“O thought that deserved to be written about,” she said. “They were 16 minutes to touch down. They were going to be gloried back here on Earth, and instead they were gloried in heaven.”

Sachara, who collects newspaper clipping of the pope, said her view of life and death inspired the poem.

“Why you’re born, God puts his breath into you, and when you die, He takes it back,” she said. “It was a very sad thing for the people on Earth, but it must of been quite a pleasure for God to meet them.”

Sachara’s religious beliefs have inspired her throughout her life. In fact, her love and interest in Pope John Paul II is what inspired her to write a book of sonnets which she calls the crowning achievement of her life.

“That’s the book I gave to the pope in 1987,” she said as she pointed out a copy of “Pope of Peace,” a collection of 72 historical sonnets that made up the life of Pope John Paul II.

“I made up my mind to put together this book, and we did it in two months without a flaw,” Sachara said of herself, a publisher and a calligrapher who never met and lived in different parts of the country putting Sachara’s work to print.

“None of us knew each other, but it was us together,” she said.

The inside page of the book reads “For Andrzej Jawien, light bearer, wanderer of the world, keeper of the sheep.” Jawien was the pen name the pope secretly used to write under while he was studying in the church.

A thousand copies of the book of sonnets was printed, and about 400 of them still remain. Sachara said she would sell any of her remaining copies for $5 a piece, although they once sold for as much as $20 a copy.

Of the 1,000 copies printed, one stood out with its leather-bound cover. That copy of “Pope of Peace” was intended for Pope John Paul II himself.

It’s a book no one in Gilroy has ever seen, Sachara said, because the day she received it from the printer, it had to be given to a bishop in Monterey to go to Los Angeles. From there, it would be inspected – as all gifts to the pope are before making their way to the Vatican.

While she had to wait for word back for quite a while and was at times disappointed with the lack of a response, but she finally heard back from the Vatican in the form of a thank you letter for her gift to the pope.

“It was quite an achievement, considering I’d never done anything like that in my life,” she said. “There’s not been a pope like him ever. To me, he’s the personifier of peace in a wild, wicked world.”

Growing up, Sachara always wanted to become a journalist.

“I always wanted to be part of the newspaper business,” she said. “That was all I wanted to do.”

The native of the Midwest went to Notre Dame College during World War II.

“We went year-round to earn a four-year degree in three years,” she said.

However, her first experience trying to get a job for a newspaper turned her off of her lifelong goal.

“Here’s a big shot editor with a cigar in his mouth who said, ‘You have a wedding ring,’ ” she said. The editor refused to offer her a job, saying he didn’t want to hire a woman who might leave the publication for personal reasons.

Sachara was crushed.

“I never looked for another newspaper job,” she said.

However, she and her husband, Gene, an engineer had three children and found their way to Gilroy in the 1970s. While raising her children, she found time to write columns for The Gilroy Dispatch, joined poet societies and still continues to write.