If you’ve never visited Fremont Peak, this is the weekend to go.

Drive up Sunday to the top of the South Valley mountain top that

straddles the Gabilan Range between San Benito and Monterey

counties and you and your family can participate in the fun of the

annual Fremont Peak Day.

If you’ve never visited Fremont Peak, this is the weekend to go. Drive up Sunday to the top of the South Valley mountain top that straddles the Gabilan Range between San Benito and Monterey counties and you and your family can participate in the fun of the annual Fremont Peak Day. This year’s special celebration marks a centennial milestone.

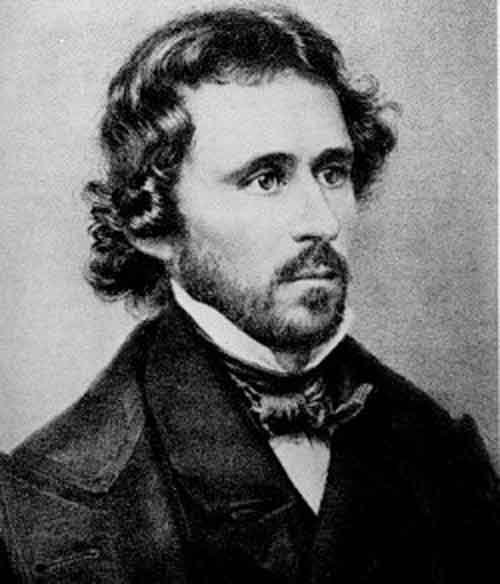

Fremont Peak is an important landmark for the South Valley. On a clear day, its summit can be seen from the four largest communities in our region – Morgan Hill, Gilroy, Hollister and San Juan Bautista. As you might expect, the mountain peak was named after a guy named Fremont. John Charles Fremont, to be exact.

Inspired by his father-in-law, a powerful senator named Thomas Hart Benton, Fremont was a U.S. Army captain who believed in a doctrine guiding mid-19th century America called “Manifest Destiny.” This was the ideology that God had destined the United States to stretch across North America from sea to shining sea. Unfortunately there was just one little bitty hiccup in achieving this dogma. The nation of Mexico happened to control all the land in the southwestern region of the continent – including territory that makes up what’s now the state of California.

The fact that California belonged to Mexico didn’t dissuade America from going forward with its Manifest Destiny aspirations. In 1846, Captain Fremont and 60 U.S. Army “surveyors” came to California and started to scout out the land here. Strangely, they brought no survey equipment on this expedition. They did, however, come well-armed with the latest in 19th century military weapons. That might be an important clue suggesting Fremont’s purpose wasn’t exactly a pursuit of scientific discovery.

Mexico’s General Jose Antonio Castro gave Fremont permission to explore California’s Central Valley region. However, Fremont somehow strayed off course and roamed the coastal region where he was able to spy on the population of Mexico’s presidio forts at Monterey and Yerba Buena (now the city of San Francisco). Castro became a bit peeved by Fremont’s failure to obey his instructions. The general ordered his troops to pursue the Americans and keep them from making trouble. International tensions were brewing between the two countries because the U.S. had annexed Mexico’s territory of Texas the previous year, and Fremont’s rascally wanderings around California weren’t helping matters.

In their game of keep-away from Castro, Fremont’s group of men in early March 1846 found themselves on top of a mountain top then called Gabilan Peak after the hawks that flew around it. It was the highest point on the Gabilan Range, and the Americans could look down on the sleepy village of San Juan Bautista where Castro had his headquarters. At this rocky summit, Fremont raised the American Stars and Stripes in international defiance of Mexico’s sovereign authority.

For three days, Castro and Fremont duked it out in a war of words. The determined Fremont refused to budge until the evening of March 9. That’s when the sapling holding the American flag blew down in the the strong Pacific breeze. Fremont superstitiously took it as a bad omen and he and his men left the peak the next morning to cross over Pacheco Pass.

Many years later, the volunteer fire department in San Juan Bautista started a tradition of raising a flag in the mission plaza to commemorate the historic incident on top of the peak 11 miles away. They did this annually for years until 1908 when the Native Daughters of the Golden West, a fraternal group dedicated to preserving California’s colorful past, took on the responsibility. A few years later, the Native Daughters brought the flag-raising event up to the peak itself. People from the mission town at first rode horses up the winding road to participate. Later, they drove automobiles.

This year’s Fremont Peak Day will be a special one.

“The Native Daughters have been involved for 100 years in San Juan Bautista’s raising of the flag,” said Georgana Gularte, a member of the organization. “Parlor 179 of San Juan Bautista is making an effort to invite all of our sisters in the state and their guests.”

Everyone is welcome to the event Sunday. It’ll be a family-oriented affair with a free barbecue beginning at 11 a.m. and the playing of taps around noon. For kids, there’ll be lots of old-fashioned games. But the highlight will be the peak itself, from which you can get vistas of the entire South Valley as well as the Monterey Bay.

Fremont Peak Day is a great way to learn a bit about one of the South Valley’s most historical land marks – and one of its most colorful characters who has gone down as a legend of the American West.