Of the historic people connected to the Mission San Juan

Bautista, Father Estevan T

ápis is the most fascinating. If you happen to be at the mission

church on Saturday – the 210th anniversary of its founding –

consider that Tápis might very well be there in spirit, too.

Of the historic people connected to the Mission San Juan Bautista, Father Estevan Tápis is the most fascinating. If you happen to be at the mission church on Saturday – the 210th anniversary of its founding – consider that Tápis might very well be there in spirit, too.

The priest would certainly be pleased to see that the Mission San Juan Bautista community celebrates its birthday with a festival held in its olive grove. This event always includes plenty of music – appropriate entertainment because Tápis helped San Juan Bautista gain renown in early California as “The Mission of Music.”

Born Aug. 25, 1754 at Santa Coloma de Farnes in Catalonia, Spain, Tápis devoted his life to God by entering the Franciscan order on Jan. 27, 1778. In 1786, he voyaged across the Atlantic Ocean to begin service at the mission college in San Fernando, Mexico.

Four years later, Tápis traveled to the frontier of Alta California to help in the administration of the mission churches the Franciscans were building. He served at Mission San Luis Obispo until 1793 when he moved to Santa Barbara. While there, the prominent Father Fermin de Lausen (a successor to Father Junipero Serra) died in 1803. Tápis was soon appointed to fill Lausen’s role as president of the mission chain. He did such a fine job that Catholic Church leaders elected him to serve in that office for three terms ending in 1812. He also served as the “vicario foraeno” (an official representative) of the Bishop of Sonora for California. Among Tápis’ achievements as a leader, he founded the Mission Santa Ines on Sept. 17, 1804.

In his position of authority as Father-President, the priest journeyed frequently along the El Camino Real – the dirt road connecting the various mission sites one day’s journey from each other. He presided during a difficult period. Mexico began its fight for independence in September 1810, forcing Alta California’s missions to be entirely self-sufficient because Spain’s government no longer provided supplies for their continued operation. The quality administration Tápis showed during this trying time proved him to be a true leader indeed.

San Juan Bautista, the largest mission church in the chain, must have been Tapis’s favorite because upon his retirement as president in 1814 he chose to spend the last years of his earthly life here. On Feb. 13, 1815, the 60-year-old Franciscan arrived at the charming mission overlooking the Gabilan Mountains. He found himself taking confessions from neophytes and teaching Indian boys how to read and write.

At San Juan Bautista, the padre was especially loved for his tremendous talent with music. He spent time preparing the Indian choir for High Mass on Sundays. To help the singers learn Gregorian chants or sacred hymns such as the “Ave Maria,” he developed a special system for a two-sided song board.

“He was very musically inclined,” said Carla Hendershot, a member of San Juan Bautista’s Plaza History Association. “He’s credited with using the four color notes in the choir books so that each of the choir members could know which part they were suppose to be singing.”

His famous sheets can be seen in the mission’s museum, she added.

Besides creating music, Tápis also had a skill for creating art. Hendershot explained that noted art historian Norman Neuerburg discovered that the padre’s designs on the choir books also appear on the “reredos,” the large ornate display behind the altar holding several carved wooden statues of saints and angels.

“We believe that because of the design that’s on it, Tápis might have sketched it out and showed the carpenter how to paint it and what colors to use,” she said.

Tápis died Nov. 3, 1825, and was buried the next day near the altar of the mission church’s chancel. In the burial registry, the church’s Father Luis Gil describes him as a devote and compassionate man. “In truth Fr. Tápis exercised his apostolic ministry to edify all,” Gil wrote. “Hence it is that he was a blameless Religious, worthy of the highest praise.”

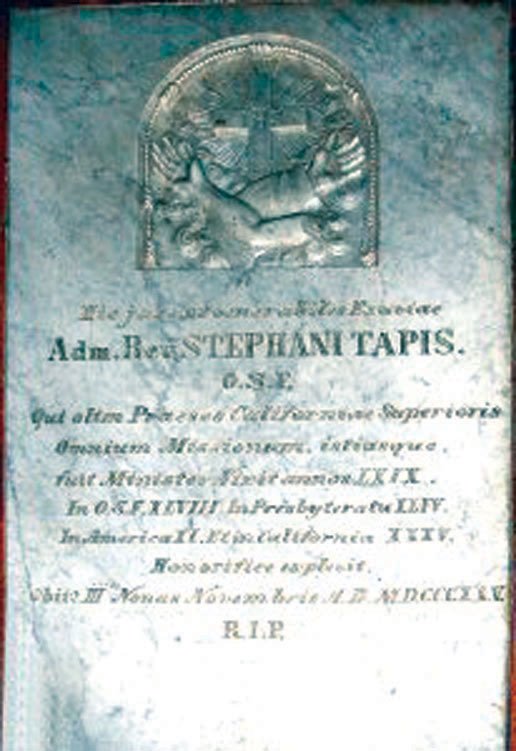

For half a century, Tápis’ burial site lay forgotten. It was re-discovered in 1875 when repairs were done to the floor. The church placed a marble slab inscribed with Latin over the grave; it still remains at that spot.

Father Tápis’ greatest monument, however, was making San Juan Bautista the Mission of Music. He knew music is a language that touches the soul. He knew that when we hear inspiring music, we hear the voice of God.