City Administrator Jay Baksa, the man hailed as a budget wizard

and at times criticized for over-reaching his authority, has

announced he will retire after 24 years at the helm of City

Hall.

Gilroy – City Administrator Jay Baksa, the man hailed as a budget wizard and at times criticized for over-reaching his authority, has announced he will retire after 24 years at the helm of City Hall.

More than 200 city employees packed the seats and lined the walls of council chambers Wednesday morning to hear firsthand Baksa’s announcement that he will leave the city at the end of the year.

“He wanted employees to hear it first from him, rather than anyone else,” Mayor Al Pinheiro said. “You could see the sadness in people’s faces. They were very silent. They were just taking it in. You could see there was a little bit of surprise.”

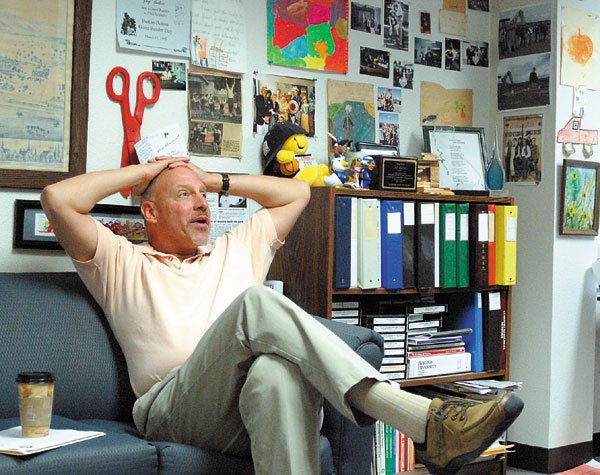

Afterward Baksa and the mayor sat down in his office and talked about the decision that caught many City Hall watchers off guard, despite the fact that his retirement had been discussed for the past few years.

“This has been in the planning quite a while, but intensified over the last year,” Baksa said. “My wife wanted me to retire on my 55th birthday, but the city had too many balls in the air for that to happen. The decision was a family one, primarily because of planning my finances and wanting to enjoy things while I have some years left.”

Retirement will afford a chance to focus on his family and his passion for Civil War history, Baksa said, as well as continue volunteer work for the Gilroy Rotary Club, a coach for the Gilroy High School junior-varsity basketball team and involvement in a myriad of other groups.

The city also has wrapped up its biggest phase of new construction in history, with a list of projects that include a new police headquarters, a remodeled downtown and a widened Santa Teresa Boulevard, the city’s western traffic artery.

Baksa, who turns 56 June 25, has served as the top administrator in Gilroy since 1983 and is the longest-serving city manager in Santa Clara County. During his tenure, Gilroy doubled in size from 23,000 to 50,000 residents and City Hall grew from 126 employees to 283.

Baksa steered the city through environmental scandal early in his career, helped guide the city’s growth during the boom years of the ’90s, and more recently, kept Gilroy’s budget in the black while countless other California cities struggled to pay their bills. His leadership has inspired plaudits from employees and residents, though some have complained in recent years that Baksa wielded too much power over the city’s fate at the council’s expense.

“We’re very sad to see that Jay has made this decision,” Pinheiro said. “I’m one of those people that would say ‘Just a few more years,’ and then after that ‘just a few more years.’ But that wouldn’t be fair to his family.”

Council will begin the recruitment process for a replacement in mid-June after budget season winds down, Pinheiro said. The city plans to cast a nationwide net as it seeks to replace a man that is the among the last of the old guard at City Hall.

Baksa started “succession planning” four years ago for himself and a number of other department heads nearing retirement. The work included delegating much of the daily budget and personnel management to newly created department heads, hiring an assistant city administrator to deal with fleet supervision and instituting performance measurement standards. The changes were intended to let Baksa and his successor turn their gaze from budget details to “macro issues” and “global policy” changes, Baksa explained.

“We want to make this transition as seamless as possible,” Baksa said. “I’ve tried to build an organization that if I left tomorrow, no one would know. I have confidence that excellent department heads will do a great job with the transition until we have a new city manager.”

The Man Who Beat Sewergate

Baksa arrived in Gilroy with nearly a decade of experience as a city administrator. He worked as a city manager in Cortez, Colo., and before that, as an assistant city manager in Delaware, Ohio. Neither of those jobs prepared him for the firestorm that lay in wait in Gilroy.

Three weeks after joining the city in 1983, news broke that the former city manager and other top-level employees had orchestrated and covered up sewage dumping into a local creek after two years of heavy rain overwhelmed the system. Within three weeks, Baksa was interviewing city employees under oath to learn what they knew about the situation. Within three months, the state imposed a building moratorium on Gilroy. And over the next few years, Baksa found himself testifying in front of district attorneys, the state attorney general and countless other agencies as he struggled to clean up an environmental mess and repair City Hall’s tarnished reputation. The building moratorium that hobbled Gilroy financially through the 1980s was finally lifted in 1991 with the completion of a new sewer plant that the city jointly operates with Morgan Hill.

“For the first three or four years, all I did was work on Sewergate,” Baksa said. “That is probably the one thing that I have the greatest pride in. Taking a situation that a judge called the worst he’d ever seen to this day, where we have an award-winning South County Regional Wastewater Authority and tons of regional partnerships.”

Sewergate was far from Baksa’s only accomplishment, according to Roberta Hughan, who served as mayor from 1983 through 1991.

“He’s probably the best city administrator as far as money management,” she said. “He kept us going in Gilroy when some cities were having trouble. We had the first three-year budgets in the county, maybe even in the state, then it became state law.”

Hughan also pointed to a less well-known episode from Baksa’s early years at City Hall. In the early ’80s, Baksa approached Hughan and told her that he had analyzed all the salaries of city employees.

“He found that with one exception, every woman made less than every man,” Hughan recalled. “So what he did was suggest giving 5 percent raises for three years to those job categories that were quote, unquote ‘women’s jobs.’ That was a women’s rights issue.”

Baksa cultivated his reputation as a budget hawk over the years, and department heads often joke in public budget sessions that he demands an accounting of every paper clip and pencil in their annual budget requests. His conservative approach to budgeting has been lauded for keeping the city in the black as the economy slowed in the early 2000s and the state began raiding local tax coffers.

Mayor Baksa?

Yet Baksa is not without critics, and some council members have pushed back in recent years, demanding greater control over the budget process and accusing Baksa of excessive influence on city policy.

Councilman Craig Gartman has long been a critic of Baksa and certain departments within City Hall, criticizing them for infringing on council’s policymaking authority, not properly executing the will of elected leaders and not informing them of major developments. His gripes began in summer 2006 when councilmen were caught flat-footed by a major mall proposal that Baksa knew of for months.

Complaints about Baksa’s role in city government peaked earlier this year in a series of scandals surrounding the secret retirements of Gilroy’s top two police chiefs. Baksa negotiated deals with the chiefs that allowed them to formally retire but remain in their jobs, a deal that allowed them to collect pension and part-time pay.

The deal was hailed by most city councilmen as a money-saver for the city, but Gartman claimed Baksa violated city charter requirements by failing to inform council of their departures. The situation grew more embarrassing when Assistant Chief Lanny Brown was forced to abruptly leave service after learning that his retirement was not handled properly under state pension laws.

During the Wednesday announcement to staff, Pinheiro told city employees that city council did not ask Baksa for his resignation, according to an employee who asked not to be named.

Some city employees have grumbled privately about a wage package Baksa recently negotiated for top city managers. Baksa defended the shift in pay ranges, which affect half of Gilroy’s 40 non-union managers, on grounds that some union workers were earning as much or more than their bosses. The ability to recruit and retain managers was also cited as a reason for the higher pay ranges.

But raises for top staff are far from the city’s greatest challenge in the future, said Baksa, who did not directly benefit from the shift in pay. The self-described “student of government” looks with fear on the increasing loss of power by cities. Residents of a mobile home park, for instance, recently learned the hard way that state law prevents city council from protecting rent controlled homes.

“There’s a real danger that if we don’t wake up, everything will be mandated by the state,” Baksa said. “That really scares me.”

And though he’s retiring, Baksa does not plan to leave the government arena entirely. In addition to volunteer work, he plans to serve as an advisor to local city managers and councils through the International City Managers Association. He plans to rely on the association to help with recruiting his replacement.

Filling Baksa’s shoes will prove difficult, predicted Don Gage, a county supervisor who served as Gilroy mayor in the late 1990s.

“We’re 50,000 people now,” Gage said. “It’s pretty hard to keep a handle on everything (in a city that size) and Jay’s done a good job of handling everything. A new administrator won’t be able to do that.”

As for criticisms of a man he helped hire nearly 25 years ago, Gage brushed them aside: “It always bother me when people challenge him, thinking he’s doing all these things against the city. He always had the city’s best interests in mind. He’ll be sorely missed.”