n by Melania Zaharopoulos

Staff Writer

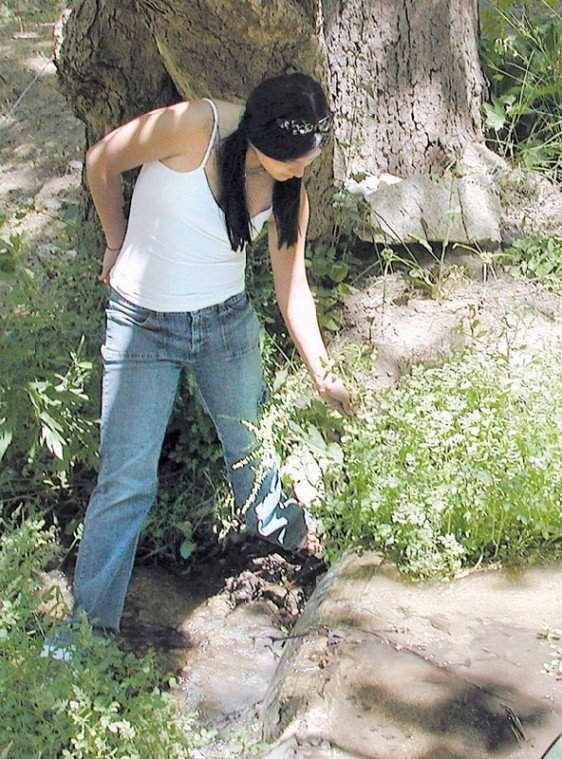

“Here it is,” said Kanyon Sayers-Roods, stooping by the creek next to her Indian Canyon home just outside Hollister. She plucks a small plant from the creek’s bank, pointing to its single broad leaf.

“This is miner’s lettuce. It’s getting kind of late in the season for it. See? It’s dried out.”

The 16-year-old points to the plant’s shriveled flower, once a brilliant white, that has now turned a translucent brown, but the real key to the plant’s over-maturity is its color. The stalk has begun to turn a strikingly rich red color, marking the miner’s lettuce as past its time. A fresh piece might turn white or pink at the base, but a green stalk is preferable.

Sayers-Roods has grown up on this land, searching the local landscape for the nuts, berries and greens that have sustained her people – the Mutsuns – for generations. But even those who don’t have a lifetime of experience with the wild edibles dotting the local landscape can enliven their next dinner with a few of the items in her

catalogue. With a little creative flair, they can create tempting dishes with plants such as chickweed, watercress, acorns and blackberries, but they’d better hurry. Summer’s heat dries out most delicate greens, and many don’t return until fall.

Gathering is a way of life unfamiliar to most Americans, but Sayers-Roods and her mother, Ann Marie Sayers, prefer to live off the land.

“We had a gentleman come up to the house and he said, ‘All this space and you don’t have a garden?'”said Sayers. “It was perfect timing because right then, Kanyon came through the door with a huge bunch of greens. I told him, ‘Why would I need one?'”

Gathered foods, like those Sayers and Sayers-Roods collect, have traditionally made up 50 percent or more of native diets in the South Valley, according to Sharon Franklett, a biologist at Pinnacles National Monument, and early pioneers learned to gather many of their foods as well.

“It’s pretty amazing to think that almost none of us know this information today,”said Franklett. “Just 150 years ago, this is how people lived.”

Sayers and Sayers-Roods make local blackberries and elderberries into syrups, jams and wines in the spring and fall, brew tea with local mint and flavor stews with wild bay leaves.

Sayers-Roods gathers chickweed, a small-leafed groundcover that sprouts dainty white flowers, and watercress, a densely packed green, to add to the miner’s lettuce and form a local salad. She’s not all that fond of dressing, so she came up with her own method of adding taste and texture.

“I throw in fruit, vegetables, anything that’s about to go bad but hasn’t quite yet,”said Sayers-Roods. “The fruit adds its own sweetness, so it flavors the greens.”

Unfortunately, the leafy greens of spring aren’t as plentiful as they were earlier in the season.

“Things are starting to dry up a little, but you can still find fresh things in the shady places,”said Sayers-Roods, pointing to the shriveled flowers on some plants and the drooping leaves on others.

Still, items like mint, which some locals often confuse with stinging nettle, will be good late into the season.

“You can always tell the mint because it gets little purple flowers on its stalk,”said Sayers-Roods, who points out the plant’s square stalk, another tell-tale sign of its non-poisonous nature.

Some of the things adventurous spirits in the area might gather do have to be treated before they can be eaten, though, said Franklett.

“If you gather acorns, which have a lot of protein and can be used to make pastes or meal or flour, you have to rinse them out and leech them so you can grind them

for eating,”said Franklett, who also wished to emphasize that people cannot gather vegetation, dead or alive, from national parks.

Mature acorns – which are brown – should be gathered from the ground or shaken from the tree, said Sayers, and inspected for holes before they are allowed to sit

and dry so that their caps can be more easily removed. Acorns grown in different areas have varying tastes and degrees of bitterness, but the acorns of valley oaks are generally preferred because their short, fat shape is larger and meatier than the small, pointed acorns of the Coastal Live Oak, she said.

To remove the tannic acid in the acorn, cut each one in half or into quarters, then cover in water. Soak and repeat several times over the course of a couple days, said Sayers, or for an added dose of protein without the work, Franklett suggested looking for the cones of gray pines, which produce large, tasty nuts.

For more on local edibles, pick up a copy of “The Flavors of Home: a Guide to Wild Edible Plants of the San Francisco Bay Area” by Margrit Roos-Collins or log on to the Bay Area Hikers group for more information at www.bahiker.com/plantpages/edibles.html.