Q: My memory isn’t as good as it was when I was younger. Are

there things I can do to help this common problem?

Q: My memory isn’t as good as it was when I was younger. Are there things I can do to help this common problem?

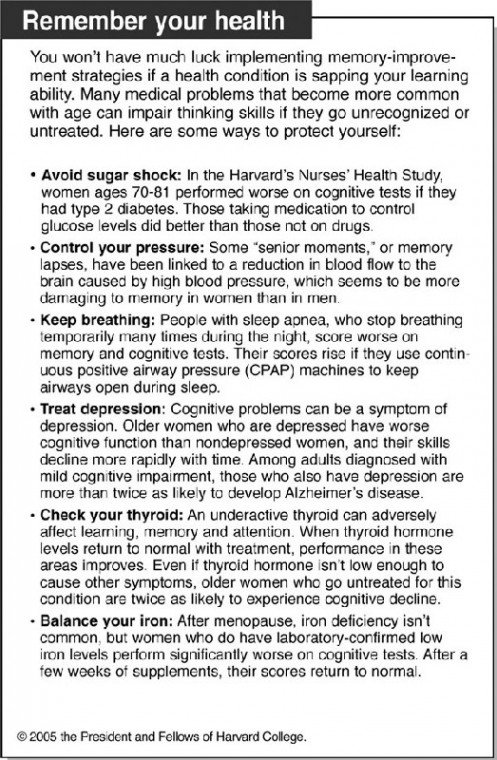

A: Memory changes are common as we age, with most people noticing a decline after about age 50. Certain medical problems that become more common with age can impair thinking if they go unrecognized or untreated (see accompanying sidebar).

But for most people, memory problems stem from normal, age-related changes in the brain that slow thinking, making it harder to learn new things quickly or to ward off distractions. The good news is that most people can sharpen their minds with proven, do-it-yourself strategies.

Here are some ways to boost your ability to remember as you age:

• Believe in yourself: Older learners do worse on memory tasks if they hear negative stereotypes about aging and memory. But they perform better if they hear messages about memory preservation into old age. Believing that you can improve can inspire you to practice memory skills that will keep you sharper.

• Economize your brain use: Don’t waste mental energy remembering where you laid your keys or the time of your granddaughter’s birthday party. Take advantage of calendars and planners, maps, shopping lists, file folders and address books to keep routine information accessible. Designate a place at home for your glasses, purse, keys and other items you use frequently.

• Organize your thoughts: New information that’s broken into smaller chunks, such as the hyphenated sections of a phone number, is easier to remember than a single long list, such as financial account numbers or the name of everyone in a classroom. To help recall a long number, notice patterns such as repeated digits. In the classroom, group the children by row and gender to help learn their names.

• Use all your senses: The more senses you use when you learn something, the more likely your brain will retain the memory. For example, odors are famous for conjuring memories from the past, such as visits to a cookie-baking grandparent. A recent study found that adults had better recall of images if the pictures were associated with pleasant smells.

• Expand your brain: Widen the brain regions involved in learning by reading aloud, drawing a picture or writing down the information you want to learn (even if you never look back at your notes). Creating a visual image makes it easier to remember and understand because it forces you to make the information more precise.

• Repeat after me: When you want to remember something you have just heard or thought about, repeat it out loud. For example, if you’ve just been told someone’s name, use it when you speak with him or her: “So, John, where did you meet Camille?”

If you place one of your belongings somewhere other than its designated home, make a note of it aloud to yourself. And don’t hesitate to ask for information to be repeated.

• Space it out: Repetition works even better if you extend the repetition over increasingly longer time periods. If you’re trying to master complicated information, restudy the essentials after increasingly longer periods of time – once an hour, then every few hours, then every day.

• Make a mnemonic: Mnemonic devices are creative ways to remember lists. One example is an acronym, such as the word RICE to remember first-aid advice for injured limbs: Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation. Another is story mnemonic, a brief narrative in which each item cues you to remember the next one. For example, the sentence “The dog knocked over my glass of milk so I have to wash the floor” could remind you that your dog has a vet appointment, you should pick up your new glasses, and you need to buy milk and floor cleaner.

• Challenge yourself: Engaging in activities that require you to concentrate and tax your memory will help you maintain skills as you age. Discuss books, do crossword puzzles, try new recipes, travel and undertake new projects or hobbies. Again, challenge all of your senses: Try to guess the ingredients in a restaurant dish; give sculpting or ceramics a try; sample different types of music.

• Take a course: Memory-improvement courses are becoming more common. Choose one run by health professionals or experts in psychology or cognitive rehabilitation. Stay away from courses that center on computer or concentration games, which generally won’t help you with real-life memory problems. Select a course that focuses on practical ways to manage everyday challenges.

Submit questions to the Harvard Medical School Adviser at www.health.harvard.edu/adviser.