After a working a 17-hour day with no breaks, farm worker and Gilroy resident Rogelio Lona remembers driving home to sleep a few hours before waking up at 4 a.m. to do it all over again.

“Back then, it was normal for us. Any place we worked, we could not defend ourselves because they would fire us,” 63-year-old Lona said.

Like many farm workers in the 1970s, Lona endured abuse, unsafe working conditions, no overtime or benefits and low wages.

Lona could not sit back and watch it happen. In 1980, he joined United Farm Workers, and for the last three decades, he has dedicated nearly every spare moment to marching, striking, organizing his co-workers and negotiating with lawmakers for better working conditions for farm workers.

“He works expecting no recognition,” said Lona’s friend and United Farm Workers coordinator, Santos Quintero.

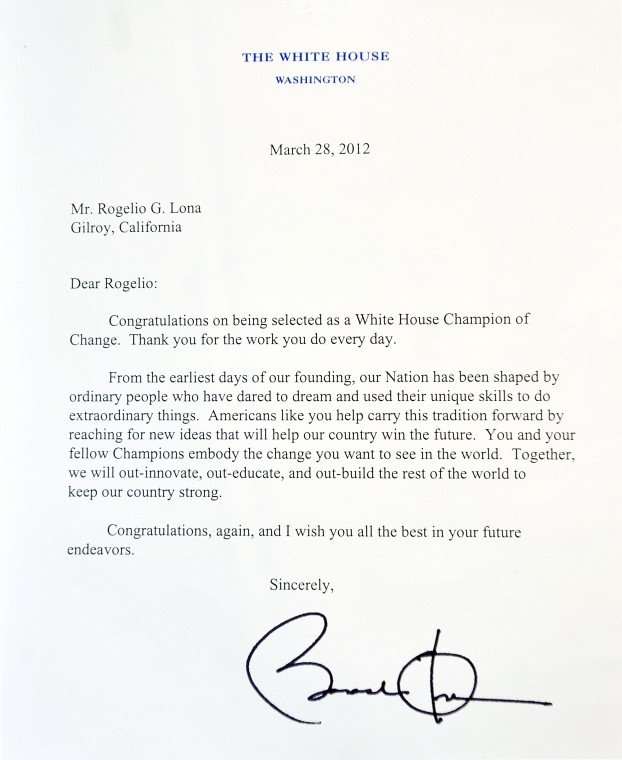

But on March 29, Lona got the ultimate recognition: a White House award that compared him to his mentor and inspiration, Cesar Chavez, forerunner for farm worker’s rights and founder of UFW.

The Cesar Chavez Legacy Award is part of an ongoing White House program “Champions of Change,” where people across the country are recognized for doing extraordinary work in their communities.

When Lona, a small-framed man with a toothy, warm smile framed by soft wrinkles, first learned he was to be honored with an award from the White House, he thought it was some kind of mistake.

“Why me?” he said over the phone to Quintero, who gave him the news.

A White House committee chose 10 winners from more than 200 nominees, a White House official said, and that Lona stood out for his lifetime commitment to improving the lives of farm workers, and for serving as a leader while continuing to be a farm worker himself. Lona is a mushroom picker at Monterey Mushrooms in Morgan Hill, where he has worked for 37 years.

To Lona’s surprise, President Barack Obama made an appearance at the ceremony.

“I saw the president like he was a friend,” he said. “I am so lucky.”

White House honor ‘not about me’

The audience held their breath and listened close as Lona spoke at the event, said Quintero, who attended.

“‘Rogelio, the struggle will never end, we must always be prepared,’ these are the words that our farm worker leader Cesar Chavez used during organizing meetings,” Lona said to the audience of 150. “Now, I always keep those words in my mind and my heart. They help me to continue with my job as a union representative. They help me to administer, enforce and guard our union contract. They help me to organize and fight for those issues affecting my co-workers and community.”

Lona knew Chavez personally through monthly UFW meetings.

As the only farm worker who won the award in a group, of doctors, lawyers and professors, Quintero said Lona truly made an impact on the audience.

“I mean, it’s the White House. You’d expect doctors and lawyers to be there. But people didn’t expect a farm worker,” Quintero said. Lona insisted the true award goes to the hundreds of farm workers who have held their dignity in the midst of abuse and discrimination.

“This not about me,” Lona said. “This is about the struggle of all farm workers.”

In 1981, Lona organized a strike against Monterey Mushrooms for better wages, overtime and the right to unionize. He said the conditions were often very poor – workers were expected to work 17 or 18 hours in a day without breaks in unsafe working conditions, and the company offered few medical benefits. The strike involved 300 farm workers and lasted 96 days, Lona said. The workers won the right to a union contract and although it didn’t solve everything at the time, they have since enjoyed better treatment. Today, every picker at Monterey Mushrooms is a member of UFW.

“If I compare those times to now, I can see the difference,” he said. Employees at Monterey Mushrooms now get nine paid holidays per year, and are entitled to two 15 minute breaks and one 30 minute lunch for an eight hour shift, according to Robert Vasquez, human resource manager. Employees are encouraged to report safety issues, are offered medical benefits that are almost entirely paid for by the company, and are paid overtime.

Lona’s wage depends on how fast he picks – currently he makes $2.67 for a flat of four baskets. Last week, he made $13 an hour, Vasquez said.

Lona often spends an hour or two after his shift at Monterey Mushrooms talking with other pickers through work-related problems, Quintero said.

On his days off, Lona sometimes travels to Sacramento and San Francisco to negotiate with legislators. He has even taken four trips to Washington D.C. to meet with senators. His work with the union is voluntary, Quintero said.

“He’s there all the time when we need him,” Quintero said. “He loves to do it, when you talk to him you can just tell.”

Marching in strikes a family affair

When Lona got off the phone with Quintero after learning he would be given the award, his 28-year-old daughter Lucina Lona said he turned to her with a sly smile.

“I have good news and bad news. The bad news is I have to leave for a few days.”

He paused.

“The good news is that the president wants to give me an award.”

Sitting in the small living room in their second-floor apartment on Eigleberry Street, Lucina beamed at her father as she spoke.

“I was in shock when I heard,” she said. “My dad always fights for the rights of other people but this was the first time he was recognized like this.”

Lucina said that campaigning for farm worker rights were so ingrained in her father, he insisted his wife and two daughters join him. Striking and marching became family events, Lucina said, laughing. Lucina remembers many family excursions where they would walk together, holding flags.

“Those are good memories,” she said.

Lucina said that as a child, she would watch her father become very focused when they were marching. It was his job to make sure the protest remained peaceful and positive, and he took that job seriously, she said.

Elvita Lona, Lona’s wife of 30 years who also works at Monterey Mushrooms, said that she worries about her husband, because he never rests – not only does he work eight-hour days (and sometimes up to 12), six days a week, but his spare time is consumed with union activities.

But since Elvita, 59, knows she can’t stop him, she joins in. Once a month, the two host job events at the Morgan Hill Library for pickers in need of work.

As involved as she is, there are times Elvita gets weary.

“Sometimes we have to wait on the side until he’s done doing his thing,” Elvita said giggling, through her daughter who translated.

On Wednesday, Lona picked mushrooms in a warehouse style building with trays of soil stacked about 10-feet high at Monterey Mushrooms in a rural area northwest of Morgan Hill. With a small knife in one hand, he picked four mushrooms at a time and swiftly sliced the bottoms off before throwing each mushroom into a basket according to its size.

“There’s an art to this,” Vasquez said, motioning to Lona.

Lona, wearing a hair net and baseball cap, was rapidly filling a large basket.

“Rogelio is a great mediator,” Vasquez said. He said that he and Lona work closely together to negotiate employee problems.

When Vasquez began working at the company seven years ago, he said there were 50 to 100 grievances filed per year.

“Now Rogelio and I get upset if there’s two,” Vasquez said.

Vasquez said that Lona hasn’t missed a day of work in the last seven years either, until last month when he flew to Washington D.C. to accept his award.

Lona is happy with his job at Monterey Mushrooms, especially because he gets to pick in a temperature-controlled room. (Vasquez said mushrooms grow best between 50 and 60 degrees.)

But Lona continues to fight for the rights of fellow farm workers all over California who are still facing harsh work conditions. One of the things he is currently concerned with is making sure all farm companies provide tents with water in the field, so that workers can take breaks in the shade when they need to.

“He’s the voice for the farm workers,” Quintero said. “The rest of us go to store and buy lettuce and strawberries but we don’t think about who does the job. He is the voice for those who are putting food on our tables.”