In an effort to minimize impacts on wildlife and tribal resources, as well as to satisfy critics of the proposed Sargent Mine in southern Santa Clara County, the project’s applicant recently offered to scale back their original plans for the property.

However, some of those critics—including representatives of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band—say the offer doesn’t go far enough, and would still disrupt a crucial wildlife crossing and the tribe’s ancestral home, known as Juristac.

Howard Justus, Managing Member of Sargent Ranch Partners, told the Santa Clara County Planning Commission last week that his firm is willing to move forward with an alternative project identified in the Sargent Mine draft Environmental Impact Report that would reduce commercial sand mining operations by about 28 percent. Known as “Alternative 3,” this project is considered the “environmentally superior alternative” in the draft EIR.

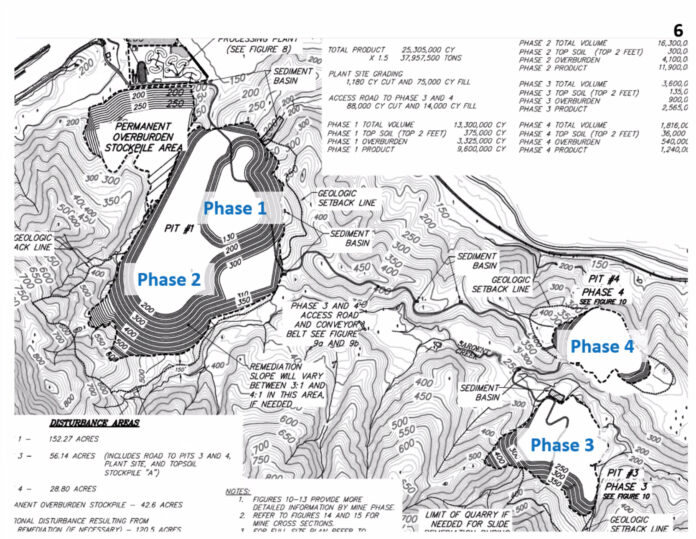

Alternative 3 would eliminate two of four originally proposed pit mine sites (phases 3 and 4) on the 403-acre site, which is located about four miles south of Gilroy and one mile south of the Highways 101 and 25 interchange. It would also reduce mining on phases 1 and 2, and move a 14-acre processing plant about one mile north of its original proposed location within the project site.

Furthermore, Alternative 3 would require the developer to build a 300-foot screening berm to reduce the mining operation’s visual impact from passing motorists, and prohibit mining activities above 500 feet in elevation, says the draft EIR.

The original Sargent Mine proposal—the primary topic of the draft EIR—called for an open-pit sand and gravel mining operation on a 298-acre portion of the property, which lies within the 6,200-acre Sargent Ranch. The original project proposal also includes a 105-acre “geotechnical setback area” to serve as a buffer from surrounding uses, says the draft EIR.

The project is meant to provide sand and gravel aggregate for contractors and public agencies for 30 years. The site is estimated to contain 40 million tons of sand and gravel aggregate. Extracted material would be transported off site by trucks and trains, according to the draft EIR.

Justus called Alternative 3 a “win-win-win solution” because it would help satisfy the region’s growing commercial needs for sand, which is a key ingredient for concrete; reduces the potential blockage of a wildlife corridor that is crucial to the genetic diversity of area mountain lions; and has less of an impact on the Juristac Tribal Cultural Landscape (JTCL).

The alternative would result in “almost no visibility” of the mining project from Highway 101, Justus added.

“At the end of the day, there’s 5,000 acres, and the quarry is going to use 7-8% of that land,” Justus said. “We see this as a bridging of historical needs with future opportunities. None of us will get everything we ask for, but we should all be pretty happy. We think there are numerous constituencies that get satisfied through this proposal.”

The draft EIR notes that Alternative 3 would “avoid and/or reduce most significant impacts” of the original Sargent Mine proposal. However, it would still result in “significant and unavoidable” impacts on “the significance of the JTCL” and on tribal cultural resources.

Justus added that Sargent Ranch Partners want to continue working with the Amah Mutsun in an effort to acquire or preserve a permanent home for the “landless tribe.”

“As an indigenous people who were moved off the land over 200 years ago, this is sacred to (the Amah Mutsun)—it’s essential to them. We want to see to it that they have access” to the tribe’s sacred ancestral lands within Sargent Ranch, Justus said.

But representatives of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band say that Alternative 3 doesn’t go far enough in preserving Juristac. The tribe has actively spoken out against the Sargent Mine project since it was in its early planning stages.

Amah Mutsun spokesperson Valentin Lopez noted that the draft EIR says Alternative 3 would still negatively impact the Amah Mutsun ancestral lands, and even disturb tribal sites that were not identified as impacted in the original mine proposal.

“Alternative 3 would still drive a stake through the heart of the sacred hills of Juristac by excavating a giant open pit mine and building an industrial complex in this highly sensitive location,” Lopez said.

Environmental advocates who have also opposed the Sargent Mine project agree that Alternative 3 isn’t satisfactory. Alice Kaufman, Policy and Advocacy Director for Green Foothills, said the alternative “would still destroy the sacred (JTCL), block the wildlife movement corridor and significantly impact air quality, transportation and the scenic views of the hillsides.”

She also noted that the draft EIR points out that for “at least one sensitive species,” Alternative 3 would create more severe impacts than the original Sargent Mine proposal.

Justus presented his firm’s change of proposal to Alternative 3 at the Aug. 25 Santa Clara County Planning Commission hearing. The purpose of the hearing was to gather public comment on the Sargent Mine draft EIR.

More than 80 members of the public spoke at the Aug. 25 online meeting, most of them against the Sargent Mine proposal. Many of the project opponents identified themselves as members of the activist group Showing Up for Racial Justice, and many questioned if the draft EIR studied the project impacts adequately in depth.

Planning Commission Chair Bob Levy on Aug. 25 wondered if Sargent Ranch Partners’ change in proposal would require the circulation of a new draft EIR. Deputy County Counsel Elizabeth Pianca said that would be determined after the current draft EIR is circulated and all public comments are applied to the final document.

The Sargent Mine applicant was required to commission an EIR as part of its permitting process. The project requires a conditional use permit from the county.

Members of the public have until Sept. 26 to comment on the draft EIR. After that, planners will compile a final EIR that will also require county approval before the project can gain a permit.

i live in charlotte county and mining has been a terrible business in florida [phosphate] all sent overseas no good for florida or the USA,