The district’s lowest-scoring school could be a model of

progress by the end of the year, school staff said.

The district’s lowest-scoring school could be a model of progress by the end of the year, school staff said.

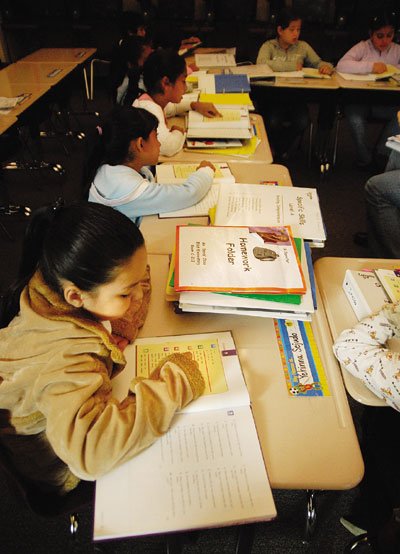

This year Eliot Elementary School is spending almost $100,000 on programs and staff to reduce class size, boost low-performing students and keep high-performing students from slipping backward. Administrators aim to increase literacy and close the achievement gap – both districtwide goals.

“In the upper grades we have a crisis, which is kids significantly below grade level,” Eliot principal James Dent said. “What you’ll see at the lower grade level is we’re attempting to prevent that.

Early student education is like a “sling shot,” he said. “Every kid is fired out of elementary school at a certain trajectory.”

The school has a history of shooting out unprepared students, as evidenced by dismal performances on the state’s standardized test – the Academic Performance Index. Eliot’s score has remained at 668 throughout its five-year test history while the district elementary school average has grown from about 705 to about 746. The state target score is 800, with annual growth of at least five points.

In September, school administrators tried to buck this trend by introducing after-school programs and new remedial programs with tailored textbooks and class-size ratios as low as 10 students per teacher. The programs were aimed at low-achieving students – such as first-graders that cannot read or do basic math.

“It’s not that they’re (just) behind,” he said. “So many students don’t know their alphabet. They can’t count to 10. They don’t know they’re colors.

“A student that’s prepared steps onto the stairs at the bottom rung,” he continued. “We’ve got some students that are down in the basement.”

Administrators also introduced advanced math and English after-school and intervention programs for high-performing first- through fifth-graders. These classes also feature lower class-size ratios and challenging textbooks, Dent said.

The result of these programs is that daytime classes appear to have been struck by a plague. In a typical classroom, 10 of 30 desks are empty, books still stacked neatly in the corner. Separating out the lowest- and highest-achieving students has reduced class size by about 10 students to about 20 students per teacher.

Two half-time teachers and three teachers teaching an extra four hours each week were hired to run the additional programs. Staffing costs plus program costs totaled about $95,000 drawn from the school’s site funds. An additional math computer program to be added soon will cost about $17,000 starting next year. The district will shoulder the first year’s cost of about $24,000 using funds from a statewide settlement with Microsoft.

Teachers are generally supportive of the new programs. While some complain of increased work, all agree the programs will boost performance by providing better-tailored education and a bump in the individualized teaching time – which in most schools is about 1.5 minutes per student per class, Dent said.

“I’m seeing some results and it’s a lot easier for our children to attend,” said third-year first-grade teacher Michele Rundle, who teaches a remedial English class. “In a big group, (low-scoring students are) lost and they can’t keep up.”

Parents are also supportive of the changes, said Parent-Teacher Association co-president Maria Zendejas, who has 6-year-old triplets in first grade, one of whom was in the remedial reading program.

“I’ve seen the difference in one of my children even a couple weeks into it,” she said.

Yet, the school’s efforts must be bolstered by parent support, said Parent-Teacher Association co-president Louise Shields, who also has a 6-year-old first-grader at Eliot.

Learning to read and do math is “not just the school’s responsibility, it’s the family’s responsibility also,” she said. “You go home and do Nintendo for the rest of the day, you’re not going to improve on those skills.”

The association pitched in by purchasing a mini-library for the principal’s office. Doorknob-tall students regularly interrupt Dent’s meetings and phone calls to come in, give him a high-five, grab a book he recommends off the shelf and scamper back to class.

With collaboration between the association and school, the school can raise its test scores and start out on a new course, Shields said.

“We’re confident it’s going to happen,” she said. “It’s a big challenge but (we’re) taking small steps. The children – they’re going to soar.”