Experts address audience’s concerns about perchlorate’s effects

on health and agriculture

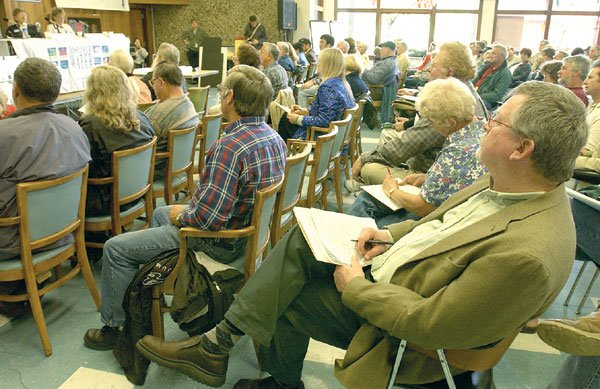

Nearly 300 people came to Gavilan College Saturday to hear

officials from various government agencies chart their progress and

knowledge on South County’s perchlorate contamination problem.

Experts address audience’s concerns about perchlorate’s effects on health and agriculture

GILROY – Nearly 300 people came to Gavilan College Saturday to hear officials from various government agencies chart their progress and knowledge on South County’s perchlorate contamination problem.

“What we’d like you to go away with today if nothing else, is a solid understanding that a lot of people are concerned … are taking this very seriously and working very hard to find solutions,” said Susan Fitts, chief of public affairs for the Santa Clara Valley Water District.

The water district is helping the Central Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board – the lead agency on addressing the perchlorate problem – while various county, state and federal agencies are also involved in gathering, studying and disseminating information.

Perchlorate is a by-product from the manufacture of flares, matches, fireworks and, in larger amounts, solid rocket fuel. A plume of the chemical has spread from an old Olin Corp. highway flare factory in Morgan Hill and contaminated several municipal wells in Morgan Hill, as well as hundreds of private wells south of the city.

Officials have made “great strides” toward defining a solution, Fitts told a crowd in the student center in her opening remarks.

Since the last meeting, she noted 1,000 wells have been tested, officials have formed a community advisory committee and a multi-agency working group, Olin Corp. has submitted initial cleanup reports, and perchlorate removal equipment has been authorized for a contaminated Morgan Hill municipal well.

Saturday’s meeting was much more subdued than the initial large public meeting on the perchlorate issue held in February, where more than 800 people overflowed a San Martin school gymnasium and several spoke emotionally at the microphone about their fears and questions.

This time, the meeting was broken up between three separate venues at Gavilan – including two halls and a large tent – and panelists rotated between locations.

Instead of an open microphone, audience members were asked to submit questions on speaker cards to aides, who interpreted and read them to the government officials on the different panels.

Need more data

County Public Health Officer Dr. Martin Fenstersheib, county Agricultural Commissioner Greg Van Wassenhove and water district engineer Bob Siegfried addressed health, agricultural and animal issues.

“We don’t pretend to know all the answers at this point,” he said of health and medical questions. “We haven’t ‘solved’ the issue at this point, but we’ve done a number of things.”

The Public Health Department has sent a second notice to physicians alerting them of perchlorate issues for vulnerable populations, Fenstersheib said, and has epidemiologists and other staff working to gather and analyze information.

Meanwhile, a special Perchlorate Medical Advisory Group of government health officials, local physicians and citizens has come together to review relevant data on perchlorate’s medical effects and determine the next steps in defining possible public health impacts from the South County contamination.

It will take some time for that group to do a proper analysis that’s based on sound science, Fenstersheib said.

It’s unclear whether South County will be the specific focus of an epidemiological study because of the small population here, but there are hundreds of other areas dealing with perchlorate problems where data can also be gleaned, Fenstersheib said.

According to the California Environmental Protection Agency, scientific studies have suggested perchlorate can disrupt thyroid hormone production. Inhibited thyroid function can result in hypothyroidism and in rare cases, thyroid tumors.

Sensitive populations include pregnant women, children and people who have health problems or compromised thyroid conditions.

While thyroid problems – the chief problem with perchlorate – aren’t a reportable condition in adults, babies are screened for thyroid function and officials have requested that information from the state, Fenstersheib said, as well as the results of an unpublished study on newborn thyroid function in other areas with perchlorate.

“That information will be very helpful to us as a first step,” he said.

A questioner asked whether thyroid impacts from perchlorate are irreversible.

While perchlorate can inhibit iodine uptake – which affects thyroid function – while it’s in the body, the chemical passes through and out of the body relatively quickly, Fenstersheib said. Ninety percent is usually gone within 72 hours.

But whether the exposure has lasting effects on the body once the perchlorate is gone from the system is a question officials don’t yet have answers to, he said. And there are “tremendous” variables in finding out, such as the effects of exposure on different people at different levels over different periods of time.

“There’s no simple answer,” he said. “The data needs to be developed over a period of time.”

Plants’ leaves versus fruit

Meanwhile, Van Wassenhove said he has asked higher-government agencies begin collecting information on perchlorate and agricultural issues immediately – but also urged them to ensure such data is interpreted properly based on facts and sound science.

The state has asked Van Wassenhove to gather and submit crop and well data to determine what wells test positive and which are being used for irrigation.

From the limited data available so far, officials know that there seems to be a significant difference in the levels of perchlorate that concentrate in plant leaf tissue versus fruit, Van Wassenhove said – something he said is initially encouraging, but needs further study and interpretation.

While there are a variety of responses to perchlorate among different plants and conditions, so far it seems there’s a “significant” difference between perchlorate concentrations in leafy tissue – where they tend to concentrate more heavily – and in fruit, officials said.

“There are a variety of responses,” Siegfried said. “If we can generalize, there are decreases in (concentration) in plants as you move from leaf tissue to fruit, and perhaps from fruit to seed.”

Someone asked whether that meant local products such as strawberries and garlic were safe to eat. Officials reiterated their responses about the different concentrations in leaves and fruit.

“Right now, the data does not indicate there is a health risk with buying those products …” Van Wassenhove said. But the lack of data means consumers have to make personal choices about consumption and risks, he said.

“We need to do more (research),” he said.

Even if a well has shown non-detect – usually meaning below 4 parts per billion because of the limitations of testing technology – there could still be perchlorate in the water used for irrigation, another questioner noted. Siegfried said excess irrigation may help keep perchlorate moving through the soil below a plant’s root system.

Animal owners may want to ask their veterinarians whether large animals should get feed that’s supplemented with iodine, Van Wassenhove said.

More testing?

In its initial draft of cleanup alternatives for the old Tennant Avenue flare plant where the contamination originated, Olin has suggested a combination of a cap and use of bacteria that would eat the perchlorate in the soil, regional water board officials said. However, they are now looking at excavation and landfilling options in greater detail as well.

The company is expected to resubmit an analysis with more technical information within the next two weeks.

A questioner said the water district’s testing area – which generally lies within Tennant, Masten and Center avenues and Monterey Road – seems out of date, as detections have been discovered beyond the boundaries.

But Olin is putting together a proposal to conduct more testing in the areas to the west, east and south of the initial area, said the regional board’s John Mijares.

“We are looking for additional sampling and looking to Olin to do it,” said water district geologist Tom Mohr.

Meanwhile, Mohr said contamination levels in individual wells will probably fluctuate up and down as underground water levels rise.

Water levels have risen 12.5 feet around the Olin site, generally causing a reduction in concentration of the chemical. A well near Railroad Avenue that initially tested at 98 ppb dropped to 5 ppb on a second test and below the detection threshold on the third, he noted.

Responding to another question, Mohr said residents shouldn’t have to replace their plumbing because of the perchlorate problem.

“As soon as you put clean water through your pipes, it’s flushed right out,” he said.

He also urged residents who have commissioned their own well tests to share the results with the water district.

Officials from the water district and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency also spoke about a range of drinking and agricultural water supply cleanup options that have been developed.

District 1 County Supervisor Don Gage, Gilroy Mayor Tom Springer, Morgan Hill Councilwoman Hedy Chang and former Morgan Hill Mayor John Varela attended, as did most of the water district board and representatives from U.S. Reps. Mike Honda and Zoe Lofgren and state Assemblyman John Laird’s offices. Sylvia Hamilton and Bob Cerruti from the new community action group were also present.

More than 1,800 households are still receiving bottled water from the water district or Olin.