Longtime Morgan Hill police officer Michael Brookman retired in June 2014, but he’s had no problem staying busy since then, largely by pursuing his childhood passion of historical research and preservation.

That passion led him, along with fellow South County historian Ian Sanders, to publish their latest book, A Hundred Years of Gilroy Hot Springs in May. The pair are already working on their next local history book, The History and Flavor of San Martin.

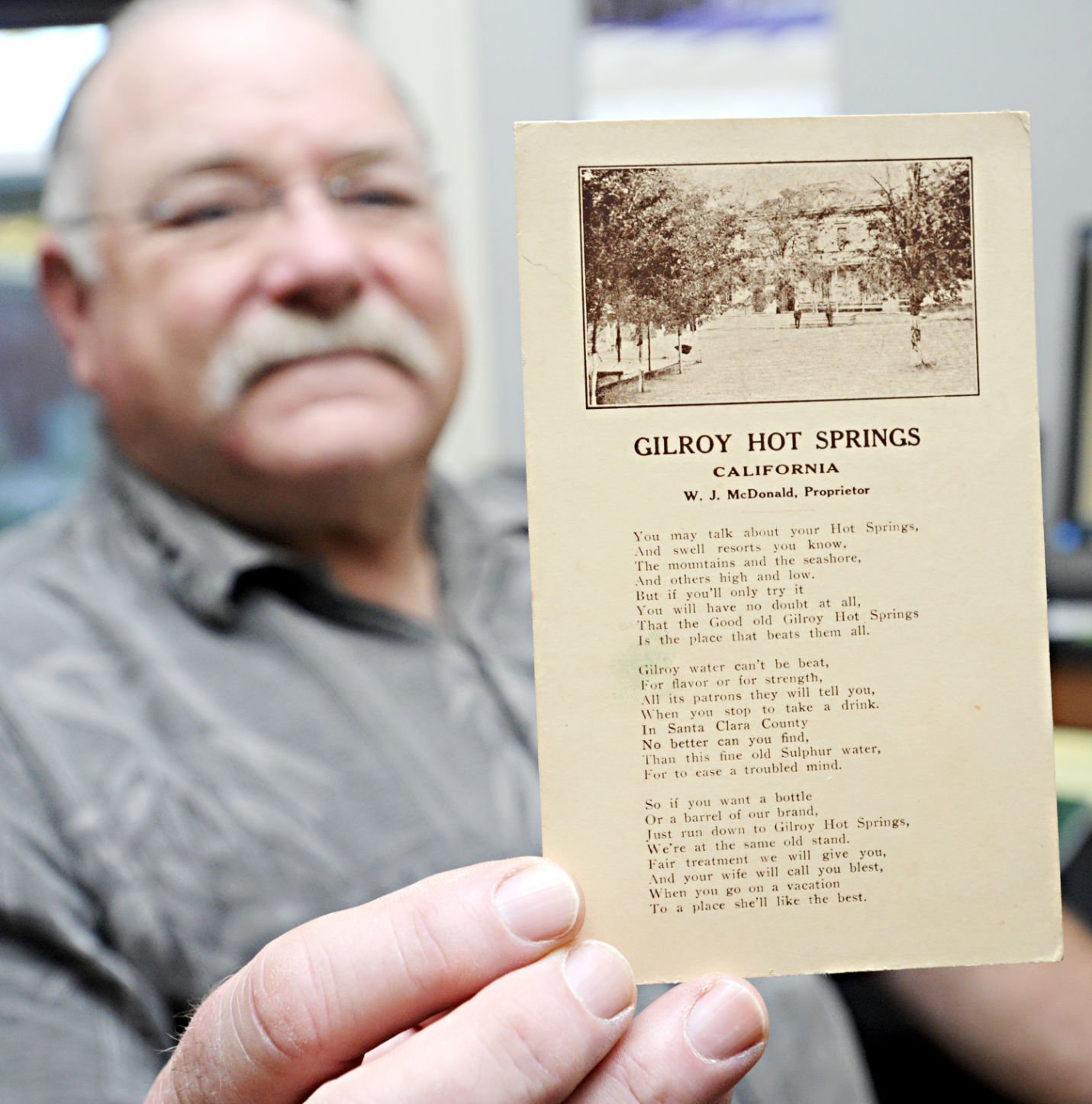

The book about the Gilroy Hot Springs focuses on the period from the late 1860s to the late 1960s, when the natural mineral spring served as the centerpiece of a resort, drawing visitors from all over the country, Brookman explained. It is mostly a pictorial history, containing dozens of images of postcards and old photographs depicting various activities and people at the resort throughout its century of use.

“There are people living in Gilroy that don’t even know there was a hot springs,” said Brookman, 55, a San Martin resident. “But it was a big, big draw. Ian and I wanted to preserve these things.”

Most of the postcards published in the book came from Brookman’s own postcard collection of more than 7,000 items, which he started building in the late 1980s.

Tucked away on a hillside overlooking Coyote Creek about 12 miles northeast of the city of Gilroy (within what is now Henry W. Coe State Park), the hot springs’ earliest recorded development as a resort was in 1866, according to the book.

“It turned out better than I expected,” Brookman said of the book. “It was a lot of fun.”

In its early days, the hot springs resort hosted a two-story hotel (built in 1868) where guests could stay for $2.50 per night. Bedrooms were also housed in about 12 separate, smaller lodging houses.

Mineral water flowed about 15 gallons per minute, at temperatures up to 112 degrees, from a ravine on the west side of Coyote Creek Canyon uphill from the creek itself. The springs still flow at a cooler temperature, Brookman said, but the property is now typically closed to the public and there are no more facilities on site.

Folklore said the spring water—full of minerals such as sulphur, iron, magnesia and soda—had strong healing properties, the book relates. Throughout the springs’ use as a resort, visitors believed that the purported medicinal properties of the water helped cure rheumatism, liver problems and alcoholism.

Civil War veterans with chronic injuries trekked to the springs in the late 1800s. The water was even bottled and distributed outside the area in the early 1900s.

The property, initially developed by Charles Twombly and George Roop, changed hands numerous times over the next 100 or so years, according to Brookman.

“Until about the 1920s—when automobiles and day trips were possible—people would stay there a week or two,” Brookman noted. “But with an auto you could drive in and drive out” in less than a day.

From the late 1930s until its closure, the resort was owned and operated by Japanese immigrant Kyuzaburo Sakata. He dubbed the resort the Gilroy Yamato Hot Springs—a name that stuck until the place closed.

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, Sakata was interned by the U.S. government along with thousands of fellow Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans. When he and other internees were released by 1945, Sakata returned and operated the resort as a refuge for Japanese-American servicemen and families.

The springs have been largely shuttered to public access since the late 1960s. By that time, as state and federal agencies piled on increasing regulations for modern resorts, it became too costly to support the isolated property with the necessary infrastructure and amenities, Brookman explained.

However, Henry W. Coe State Park staff provide docent-led tours of the hot springs grounds two Saturdays per month.

Brookman became interested in the hot springs’ history when he volunteered at Coe Park several years ago. He met Sanders, who has published two previous books on his hometown of Morgan Hill, when he started out working on a book about his postcard collection—an idea that morphed into the co-authored history of the Gilroy Hot Springs.

Brookman has been a history buff since he was a child, when he read an article about ancient Egypt in the scouting magazine Boy’s Life. He also participates in historical reenactments throughout northern California.

Brookman, a graduate of the Leadership Morgan Hill class of 1996, is well-known in Morgan Hill as a police officer who worked for the city for almost the entirety of his 30-year law enforcement career. He retired in 2014 as a corporal, always on patrol while at times helping expand MHPD’s social media presence and assisting with traffic enforcement.