Q: What causes gallstones, and is surgery the best way to treat

them? Can they be prevented?

Q: What causes gallstones, and is surgery the best way to treat them? Can they be prevented?

A: Gallstones, which can be as small as a grain of sand or as large as a golf ball, form in the gallbladder. This small sac, situated below the liver, concentrates and stores bile. Bile is a substance made by the liver that helps us digest fatty foods and absorb certain vitamins. Sometimes, the bile stored in the gallbladder crystallizes, forming solid lumps known as gallstones.

In most cases, gallstones primarily contain cholesterol and form when the bile comprises more cholesterol than bile salts can dissolve. They may also develop if the gallbladder doesn’t contract and empty as it should. About 20 percent of gallstones are pigment stones. They are made of calcium salts and a chemical found in red blood cells. Pigment stones are more likely to occur in people with certain medical conditions, such as liver disease and some types of anemia.

Women are much more likely to get gallstones than men because the female hormone estrogen increases cholesterol in the bile. This increased risk starts to drop after menopause, when estrogen levels fall. Estrogen therapy increases the risk, although the patch form of the hormone appears to cause fewer problems than the pill form.

People who are obese are more likely to have gallstones. But rapid weight loss also boosts the risk, because very low-calorie diets increase the amount of bile the body makes.

Gallstones are so common after weight-loss surgery that surgeons often advise patients to have their gallbladders removed at the time of surgery. Genetic factors may also affect the risk of gallstone formation. Finally, gallstones are more likely to occur in people with diabetes or who have high triglyceride levels.

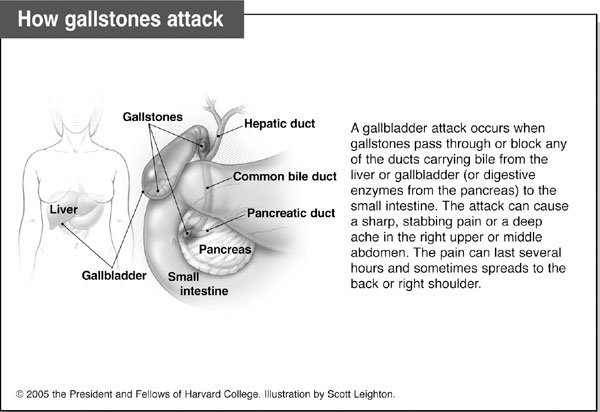

Most people who have gallstones don’t know it. They only have symptoms if the stones pass through or block a bile duct, causing a gallbladder attack (see accompanying sidebar).

If a stone lodges in a duct, it can cause inflammation (swelling) in the gallbladder, or the bile ducts in the liver. Stones also can lodge in ducts leading out of the pancreas, another organ that empties its fluids into the small intestine near the opening of the bile duct, causing pancreatitis. These are all serious conditions and can lead to severe pain, jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes), high fever, chills, nausea and vomiting. Usually, the person has to take antibiotics and have the stone surgically removed.

In most cases, gallstones should be treated only if they cause symptoms. For recurrent gallbladder attacks, the most effective treatment is to remove the entire gallbladder. Traditionally, surgery involves a five-inch incision and a hospital stay of up to a week. But these days, most people have a laparoscopic procedure. The surgeon removes the gallbladder with instruments inserted through small incisions in the skin, below the liver. This procedure requires only an overnight hospital stay and a week of recovery at home.

With the laparoscopic technique, there is a slight risk of injury to the bile ducts. And in up to 10 percent of cases, the surgeon may need to switch to a traditional type of surgery because of complications such as bleeding or old scarring.

When you don’t have a gallbladder, bile simply flows directly into the small intestine through the common bile duct. The downside: Bile in the intestine when no food is present may cause loose stools. But a bile acid-binding medication can treat the problem.

If you are unable or unwilling to undergo surgery and your gallstones are relatively small, one nonsurgical option is to take ursodiol. It is a naturally occurring bile acid that helps dissolve cholesterol. But ursodiol can take up to two years to work and will dissolve only those gallstones made of cholesterol.

Doctors may also use a technique called lithotripsy. Lithotripsy uses sound waves from outside the body to break gallstones into pieces that dissolve more easily or are small enough to safely pass through the bile duct. Unfortunately, stones are likely to recur.

As far as preventing gallstones, there’s no sure-fire method. But studies suggest that people who drink moderate amounts of alcohol are less likely to have gallstones that cause symptoms. Other research has uncovered additional habits linked to a lower risk of needing gallbladder surgery: eating plenty of fiber, eating nuts several times a week and exercising.

If you lose a great deal of weight very quickly through surgery or a very low-calorie diet, you can lower your risk of developing gallstones by taking ursodiol. Avoiding fatty foods will not get rid of gallstones, but it may make attacks less frequent.

Submit questions to the Harvard Medical School Adviser at www.health.harvard.edu/adviser. Unfortunately, personal responses are not possible.