La Jolla developer Wayne Pierce claimed he had no plans to build

a casino on the Sargent Ranch just south of Gilroy. But a website

reveals plans for a luxury gaming resort on the 6,500-acre ranch,

land sacred to a local Native American tribe.

La Jolla developer Wayne Pierce claimed he had no plans to build a casino on the Sargent Ranch just south of Gilroy. But a website reveals plans for a luxury gaming resort on the 6,500-acre ranch, land sacred to a local Native American tribe.

The website, headlined Juristac Rancho, re-opens a can of worms pertaining to a land struggle that’s hung in the air for years.

“It appears to the tribe this website may be valid for the purpose of soliciting an investor to keep Sargent Ranch from going into foreclosure,” said Valentin Lopez, Chairperson of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band. “That’s my guess.”

For a number of developers who’ve come and gone over the decades – Pierce being the most recent – Sargent Ranch, a vast expanse of undulating hills, pristine streams and unsullied natural beauty, remains tempting forbidden fruit. Currently the closest Indian casinos to the Bay Area are nearly two hours away in the Central Valley in towns like Madera.

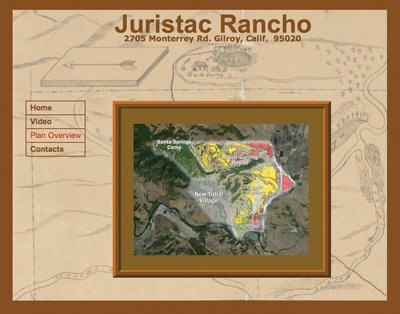

The website displays an aerial snapshot of the property, located on the west side of U.S. 101 between the Castro Valley Ranch and the San Benito and Santa Cruz county lines.

Beneath “Plan Overview,” blueprints show a “Luxury Gaming Resort” “Sand Quarry,” “New Tribal Village” and “Santa Springs Camp.”

Skip Spiering, Pierce’s representative for Sargent Ranch, is also listed as a contact on the website. He would not say why the website existed, but referred to it as “ancient history.”

Proposals to develop Sargent Ranch have been repeatedly rebuffed by Santa Clara County. In 2001 and 2002, Pierce’s early plans – before he made the connection with the local Indian tribe – were rejected by the county.

As for the website being two years old, Lopez said “it does matter in the sense they continuously said they were not interested in gaming, and here they’re presenting a proposal for gaming, and we believe that was their intentions all along. It just shows dishonesty on their part.”

Lopez suspects the “Plan Overview” on the Juristac Rancho web page could have been a last-ditch effort to secure a lifeline for Pierce’s company, Sargent Ranch LLC. As of last January, the company was under Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings.

“He’s had a lot of schemes over the years,” said Don Gage, former Santa Clara County supervisor and former Gilroy mayor.

Gage said he hasn’t seen Pierce pop his head out in a long time. He agrees the website may have been an attempt to revitalize development efforts and avoid going into foreclosure.

“I’m sure bankers are around his neck,” he said.

Either way, Gage doesn’t see things going anywhere, and speculated that Pierce owes more than Sargent Ranch is worth. He pointed out additional roadblocks to building anything on the ranch which include earthquake faults, excessive oil and tar and the fact that it’s a habitat to endangered species such as steelhead trout.

“Sargent Ranch LLC is still in bankruptcy,” confirmed Spiering Monday morning. “Quite frankly I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Pierce did not return phone calls for this story.

The battle over what to do with the property, for that matter, is emotionally heated and involves conflicting interests.

For the Amah Mutsun Indians, a band of Ohlone/Costanoan Native Americans torn by two opposing tribal councils, the ranch is a hallowed domain of heritage and history; the precious object of controversy in a quest to define the tribe’s identity.

A petition now stands fifth in line for review by the Office of Federal Acknowledgment, the first branch of the Bureau of Indian Affairs that a tribe must negotiate in its quest for recognition and a land trust. The claim has moved up the list from 13th in 2004, and two rival tribal councils of the Mutsun Indians are involved.

One faction is headed by Lopez, and another led by Irenne Zwierlein, who resigned as chairperson of the main tribe in 2000.

Both have different visions for Sargent Ranch.

“We would like to see the land preserved and protected,” said Lopez Friday, reiterating a stance he’s taken since the onset of development plans surfaced in the early 2000s.

He’d like to work cooperatively with some of the local environmental groups or county parks and recreation officials to ensure that it’s never developed and, at the same time, to allow the Mutsun to use it for ceremonies, prayer and preservation.

Zwierlein pursued a different strategy by forming her own group and striking a multi-million-dollar land deal with Pierce.

With the Mutsun vying for tribal sovereignty – the right of federally recognized tribes to govern themselves – the Mutsun would not be subject to county zoning regulations.

By partnering with Zwierlein, the deal would have allowed Pierce to sidestep county zoning stipulations and lay the groundwork to develop the property once the Mutsun were granted sovereignty.

Under an economic development plan Zwierlein submitted to the BIA, Pierce would have provided the Amah Mutsun with $21 million for a cultural center and 3,500 acres of the 6,500-acre ranch.

Of that, 500 acres would be reserved for tribal members’ homes and businesses, as well as open space and the cultural center. The remaining 3,000 acres would be leased back to Pierce.

The economic development plan obtained by the Dispatch never mentioned a “luxury gaming resort.”

“Wayne and Irene both repeatedly said that a casino was not part of the plans,” said Lopez.

In a Sept. 16, 2005 letter to the editor, Zwierlein wrote, “the Dispatch alleged that ‘obtaining sovereignty’ is nothing more than a ‘key first step’ in opening a casino. This is insulting to tribes like ours that have no interest in gaming (and have adopted constitutional provisions to prevent future gaming), and to all tribes that have worked to restore their government-to-government relationships with the United States.”

Zwierlein, in mourning for her husband Harold Zwierlein who passed away Nov. 9, was reached Monday at her Woodside home and declined to comment.

The Dispatch could not confirm if she is aware of the website, or she approved of its contents when it was created.

In a 2004 e-mail response to questions, Pierce wrote “the only consideration on the table is senior housing ranging from active adult to congregate care facilities. We will do it in a manner that respects the environment and leaves much of the land pristine.”

Had Pierce and Zwierlein’s original plan for Sargent Ranch gone through, Lopez believes a devastating scenario could have potentially involved the pair turning it into a “huge pit” for mining oil, gold, sand and gravel.

Developing the land where their ancestors fished, hunted and raised families, he pointed out, was never a goal for the Mutsun in the first place.

Former Dispatch reporter Serdar Tumgoren, who covered the story extensively, said “back in the day” there was no mention whatsoever of any gaming.

In fact, he remembered, Pierce and Zwierlein said quite the opposite.

“There is an undeniable connection between the tribe receiving federal recognition and its ability to have their way with the land – namely, making good on the development deal with Pierce,” reported the Dispatch in 2004.

Forgery of tribal papers, however, helped kill the project.

In 2007, federal officials said Irenne Zwierlein forged and mailed documents to the government in what Lopez called an attempt to cling to power.

“She is not the legitimate leader; she submitted fraudulent documents,” said Lopez, adding that Zwierlein signed a document resigning as tribal chair.

Federal scrutiny of Pierce’s past dealings slowed any plans for the ranch and, when Sargent Ranch, LLC filed for bankruptcy in January, it owed more than $90 million on the property.

Who’s spearheading the project now – if anyone – and which parties are calling the shots is unclear. Whether Pierce and Zwierlein are still a team isn’t clear, either.

“That’s’ what we don’t know,” said Lopez. “(Sargent LLC) went into bankruptcy. Last I heard, it was not foreclosed on yet.”

Lopez believes Pierce could partner with another investor up until the last minute.

But amidst hiccups such as tribal rifts and development sharks, Lopez can only reiterate his bottom line: Sargent Ranch should stay preserved and protected.

“It may be private property,” he pointed out. “But sacredness and power are still up there. We hope to be able to go up there and do ceremonies, pray and dance for the rest of time.”