When I was a kid growing up in Hollister in the 1980s, my family

took part in an interesting U.S. Geological Survey experiment.

Every Saturday evening, dad phoned a USGS hotline to report any

unusual activities we might have noticed with our dogs, goats,

chickens and geese.

When I was a kid growing up in Hollister in the 1980s, my family took part in an interesting U.S. Geological Survey experiment. Every Saturday evening, dad phoned a USGS hotline to report any unusual activities we might have noticed with our dogs, goats, chickens and geese.

The reason for this weekly ritual was to gather anecdotal data that might indicate any correlation between animal behavior and earthquake events. In the end, it turned out our animals made lousy prognosticators of tectonic activity.

With the upcoming 20th anniversary of the Loma Prieta earthquake, many South Valley people will recall where they were during that 6.9 temblor. There will also certainly be much discussion about possible ways of predicting a major shaker. Accurate quake forecasts might one day save lives and reduce property damage when a high magnitude earthquake strikes.

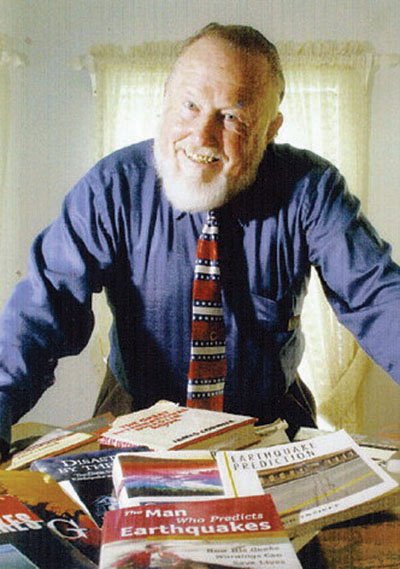

I recently had a phone conversation with someone who might have figured out a way to calculate when the crust of our planet might be getting ready to shake, rattle and roll. Geologist Jim Berkland is a legend in the San Francisco Bay Area for his unique system of predicting earthquakes.

Berkland’s controversial method might indeed work. In autumn 1989, he put himself on the record when he told a Gilroy Dispatch reporter a temblor between 3.5 and 6.0 would hit the Bay Area region between Oct. 14 and 21. His prediction was published in the Oct. 13, 1989 Dispatch. Four days later, Loma Prieta hit.

Berkland explained to me that his earthquake forecasting method incorporates several scientific factors. Among the most important is the powerful tidal forces the moon and sun have on our planet’s crust. Most people know that ocean tides rise and fall because of astronomical gravitational pull. Solid land has elastic properties and so, like water, it is also affected by the moon and sun’s gravitational attraction.

Berkland’s system looks at when the celestial gravitational forces are the strongest. During this period he can forecast a “seismic tidal window” – a period when a powerful jolt might be triggered. Essentially, the aligned sun and moon’s gravity combine to activate the release of the massive amount of tectonic energy stored in underground rock.

Berkland’s system also incorporates animal behavior. He told me that as a scientist, he was first skeptical that our non-human friends can somehow sense an impending quake. But then when he began to study classified newspaper advertisements for lost cats and dogs, he noticed a strange correlation. Before a big jolt, the number of advertisements tended to increase with statistical significance.

One theory he suggested for this effect is that the gravitational strain on the earth during the build up to a quake produces localized fluctuations in the earth’s electromagnetic field. Sensitive animal brains can somehow sense these disturbances. Tiny magnetic “compasses” in the brains are affected by changes in the earth’s natural magnetic field. If this field is disturbed by impending seismic activity in a location, the animal might become disoriented and thus get lost. Or the psychological anxiety caused in the brain by the disturbance might trigger the animal to flee the area.

I’ll admit I’m a bit skeptical about the ability of animals to sense disturbances arising from geological forces miles underground. But precedents from the past hint there just might be something to this idea that Fluffy or Fido can predict an impending temblor. History records, for example, that prior to a 373 B.C. earthquake that demolished the Greek community of Helice, droves of rats, snakes and weasels fled the city.

I believe Berkland might be correct in his theory that earthquakes are triggered by the strain on the earth from the gravitational pull of the sun and moon. And there does seem to be evidence that electromagnetic forces are released from the rock during the build-up to a quake. Shortly before the Loma Prieta earthquake, a Stanford scientist had by chance set up a magnetic field measuring instrument close to the epicenter. About three hours before the quake hit, his device showed a spike in the magnetic field 60 times normal.

Perhaps one day, California can set up a network of instruments along major fault lines that might help give our state’s citizens ample warning of “the Big One.” The relatively small cost of such an earthquake prediction system would be well worth it if it saves lives.

As for Berkland, I asked him to go on public record and offer his prediction of the next rumbler for our region. He told me that during the “seismic window” of Oct. 16 to 23, the South Valley has a chance of experiencing a tremor of 4.0 or higher. We’ll see if he succeeds in that forecast as well as he did in predicting the 1989 Loma Prieta quake.

I live in Northern California. Can you predict anything will happen in the next few years?