Fueled by wealth, desire and appetite, the spice trade

flourished not only in the times of Greeks and Romans, but most

prolifically in Europe’s Middle Ages and beyond.

Fueled by wealth, desire and appetite, the spice trade flourished not only in the times of Greeks and Romans, but most prolifically in Europe’s Middle Ages and beyond.

The exotic tastes and pungent aromas of foodstuffs like pepper, said to wash straight from the gates of Paradise, and salt, which was traded as currency in some parts of the world, mingled with those of nutmeg and ginger, cloves and cinnamon.

In decades’ worth of text books, the clamor for spices has been attributed to these items’ capability of obscuring the odor of rotted meat, but the expense of spices limited them to the upper classes, for whom these rare treats were far more than culinary costuming.

Spices were political tools, shows of wealth and spectacular treasures to give and to hoard, wrote Wolfgang Schivelbusch, author of “Tastes of Paradise: A Social History of Spices, Stimulants and Intoxicants.”

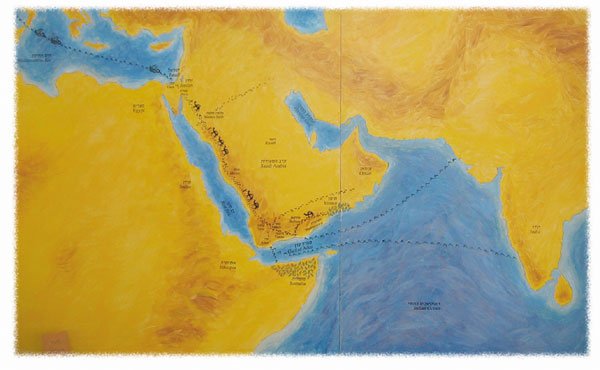

Garlic, onion and horseradish grew naturally in Europe and held little value for merchants or the wealthy, becoming the spices of the peasantry instead. Other spices, those whose flavors were rich, exotic and pungent to the European palate, had to be imported, traveling the long spice roads from Asia, India, Africa and the West Indies.

Cloves were cultivated in the Moluccas and Malaysia; cinnamon in Western India and Sri Lanka; and black pepper was grown in India and Brazil. Ginger was harvested in China and Jamaica while nutmeg and mace were also cultivated in the Moluccas.

Bandits, taxes, illness, shipwreck or sandstorms could halt or delay shipments on land and sea routes, and the trips were especially dangerous.

Today, the search for spices is less of a showy affair. You’re probably more likely just to pick some up at the grocery store, but trying something new can add a little feel of adventure to your own kitchen.

In ancient times, the Egyptians used spices extensively in burial rituals, and may have even traded them over perilously long distances, according to the Bible. Rather than kill their brother Joseph, the favored son of Abraham, his brothers plot and sell him to spice traders bound for Egypt.

The story may seem odd, but an ancient spice trade is quite probable, as evidenced by the exchange of items like a piece of Chinese silk found with an Egyptian mummy buried more than 3,000 years ago, and historical documentation provided by such famed early recorders as Pliny and Herodotus, according to Horticultural History Professor Jules Janick of Purdue University.

Simple black pepper, a product of India, was so valuable in the Middle Ages that a rise or fall in its price could affect economies from Arabia and Turkey to Western Europe in much the same way that fuel price alterations affect the U.S. economy today, according to Irwin Ziment, principal researcher for the University of California, Los Angeles exhibit, “Spices: Exotic Flavors and Medicines,” a collection viewable through the university’s Louise M. Darling Medical Library Web site (http://unitproj.library.ucla.edu/biomed/spice/index.cfm)

Ziment illustrated the price of the search for spices with the story of Magellan, whose treasure hunt was successful, in a manner of speaking.

“Magellan’s circumnavigation of the globe started with five ships which had supplies to last their 250 or so crew members for many months,” wrote Ziment. “The expedition limped home with only one ship and an emaciated crew of 18 surviving men who returned to Spain in 1522 after their three-year horrendous expedition. Despite their enormous losses, the incredibly valuable cargo of 50,000 pounds of cloves and nutmegs from the Moluccas made the enterprise seem like a commercial success.”

Today’s spice trade is fueled neither by rarity nor food spoilage. Instead, it’s been fueled by a renaissance of culinary delight as regional spices make their way to the global marketplace.

“You talk about something like cumin that 20 years ago nobody knew about unless they were a Mexican cook or a Southwest cook, and now that’s one of our top 15 spices,” said Laurie Harrsen, a spokeswoman for McCormick, a spice-producing company founded in 1889 and based in Hunt Valley, Md. “Consumers are tasting things in restaurants and being exposed to new tastes. Then they want to come home and try them.”

In fact, U.S. spice consumption has doubled in the past 20 years, with Americans now consuming a billion pounds of spices per year. Most favorites of medieval taste buds like nutmeg and cloves aren’t in the forefront anymore, as Asian and Latin spices like cardamom and cumin take off.

“The demographics are different now,” said Harrsen. “Even younger kids are exposed to different spices because they go over to friends’ houses and they might cook with the flavors of another culture. The big trend for pre-teens right now is that they’re really into Indian food. They’re growing up, and they’re going to be taking all of these really sophisticated palettes with them.”

As evidence of this trend, sales of cardamom, a popular ingredient in Indian cooking, are up more than 600 percent for McCormick since 1985, said Harrsen, who also noted that stock elements like black pepper (up 80 percent), onion, and garlic (both up 169 percent) are enjoying greater sales.

She attributes the rise to a greater demand for spices used in what used to be considered unusual ways. Pepper, for instance, is now used in rubs for meats and even ice cream at some restaurants, she said.

And while a 100 percent increase in sales may seem like a lot now, Harrsen said there’s more to come for the company.

“I would just look at the general trend of where food is going right now,” said Harrsen. “Healthy trends are what we’ve been going toward for a while, and whenever you’re eating healthy, flavor comes into play because you’re replacing other things with it.”

Traditional spices like allspice, nutmeg and mace remain popular as well, and not just for the added taste they deliver. Scent is the strongest sense tied to memory, and most of what we taste is actually information captured by our nose, forever linking certain spices to the taste of home.

Spices in your kitchen

For a few innovative ways to incorporate spices into your daily routine, here are a few suggestions from Dorothy McNett, owner of Dorothy McNett’s Place in Hollister:

• Sprinkle crystalline ginger in green or cabbage salads. Not only will it add an appealing zing, but the extra crunch of the texture is delicious.

• Apply 1/2 tsp. of ground white pepper to any pie crust mix. No one will be able to see the pepper, and the crust won’t have a specifically peppery taste, but the McNett promises guests will be amazed at the flavor of the crust.

• Add one pinch of cinnamon to pasta sauce for a similar effect.