GILROY

– Santa Clara County planners have drafted a list of 31 property

owners they say have been abusing the state’s Williamson Act, which

gives tax breaks to owners of agricultural land and open spaces.

Fifteen of the parcels are in Gilroy, Morgan Hill and the

surrounding area.

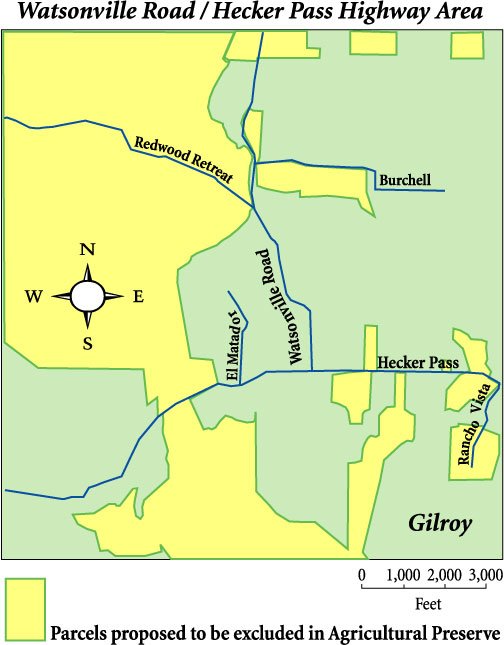

GILROY – Santa Clara County planners have drafted a list of 31 property owners they say have been abusing the state’s Williamson Act, which gives tax breaks to owners of agricultural land and open spaces. Fifteen of the parcels are in Gilroy, Morgan Hill and the surrounding area.

If county supervisors uphold the planners’ recommendations, these property owners will soon begin paying their property taxes at the same rates as residential or non-ag business property owners. How much revenue the state would recover from these properties is unknown at present. While counties collect property taxes, the state reimburses them for Williamson Act discounts.

District 1 County Supervisor Don Gage worries that Santa Clara County planners are being overzealous in weeding out those abusing the act.

“Personally, I think they’re making it too difficult for people within the act,” Gage said of the staff. “I think that there’s a lot of people out there who are not truly Williamson Act parcels, … (but) you can’t just put a rubber stamp over an area and say, ‘Everything in this area is not part of the Williamson Act.’ You may have to look at some properties individually.”

Ann Draper, the county’s planning director, said most of the discussions have been about houses on Williamson Act lands. The act requires that a house be “incidental” to the agricultural or open-space use, meaning that the latter is the dominant use. She saidher staff has been willing to approve almost anyone who can prove they have commercial agriculture.

“If there’s agriculture and the house is incidental to that, we’ve approved it,” Draper said. “Where we’ve not approved is where there’s no ag and they don’t want ag. … The state decided a couple of years ago that it would not subsidize mansion development.

“If they’ve got a commercial agricultural use, it’s very easy to show,” Draper added. “It’s when it’s extremely marginal that it’s hard.”

Ninety-nine percent of the 3,100 county properties that take advantage of the Williamson Act use the land for legitimate reasons such as commercial agriculture, public open space or wildlife habitat, according to county staff.

Of the 1 percent tagged for elimination, most had no evidence of commercial agriculture. Some had claimed their hobby gardens, pets or landscaping as farming.

“If you put one horse on the property, or one cow, that’s not really agricultural use,” Gage said.

Yet the line between personal and commercial ag use can be shaky, according to Gage. As an example, he noted a Los Gatos couple with seven acres of grapes. County staff described this as a hobby farm inside an urban service area, but Gage said the owners told him they’re getting ready to start a commercial winery. Until now, they’ve been experimenting with their small vineyard, keeping the crop to themselves.

If the intent of the act is to encourage commercial agriculture, Gage said, this is a prime example of an operation being developed with the act’s assistance.”If you set your standards too high and you force these people out, you induce growth,” Gage said. He worries that with the higher, non-act taxes, marginal ag operations would be pushed toward “the next best use, and that’s development. … Then you have the things that people don’t want.

“I’m asking the county, the staff, to step back and take a real hard look at this … before we start laying down rules and regulations.”

A recent state audit showed many instances where the county allowed abuses, such as in allowing Williamson Act property owners to subdivide land for residential development. This audit sparked the county’s current enforcement efforts. It’s a new situation for Santa Clara County, Draper said; other counties, like San Benito and Napa, annually weed out those that don’t meet commercial ag guidelines.

At a public hearing Aug. 28 in San Jose, Gage estimated 100 people, representing about 50 properties, showed up to express concern about the act’s post-audit implementation.

The county is considering setting a profit threshold to separate the tax write-offs from those the Williamson Act is intended for. In other words, to qualify as a farm, a property would have to produce a certain amount of income. The problem is that some operations make more money per acre than others. A huge cattle ranch might make less than $200 per acre annually, but a vineyard might average $1,500, according to Rachael Gibson, Gage’s land-use policy aide.

Don Silacci, of the Gilroy area, is second vice president of the California Cattlemen’s Association and past president of the county’s equivalent. He has confidence that the county and state will weed out the blatant Williamson Act abusers without affecting any real farmers or ranchers.

“Any legitimate cattleman is not in any trouble,” Silacci said. “Any legitimate agricultural thing is fine.”

Nevertheless, Silacci admitted that a $200-per-acre-per-year threshold – a figure the county has toyed with – “wouldn’t fit cattlemen.” He said he may attend the county’s next Williamson Act hearing to find out more for himself.

Because of the wealth of interest in Williamson Act changes, the county plans to hold a special hearing for that alone – probably late this month or in early October.