Gilroy

– The rivalry tearing at the heart of the Amah Mutsun Indians is

not one of clan versus clan, lineage against lineage. It is not a

clash between the San Juan Bautista Indians and those of Santa

Cruz. It is a rivalry for power, a fight to define the tribe’s

identity and secure rights to the 6,500-a

cre Sargent Ranch, considered sacred land. And that struggle

boils down to a number: Federal petition No. 120.

Gilroy – The rivalry tearing at the heart of the Amah Mutsun Indians is not one of clan versus clan, lineage against lineage. It is not a clash between the San Juan Bautista Indians and those of Santa Cruz. It is a rivalry for power, a fight to define the tribe’s identity and secure rights to the 6,500-acre Sargent Ranch, considered sacred land. And that struggle boils down to a number: Federal petition No. 120.

That number is assigned to the Amah Mutsun Band of Ohlone/Costanoan Indians. That number now stands 13th in line for review by the Office of Federal Acknowledgment, the first branch of the Bureau of Indian Affairs that a tribe must negotiate in its quest for recognition and a land trust.

Petition No. 120 is currently claimed by two tribal councils – one headed by Valentin Lopez and another led by Irenne Zwierlein, who resigned as chairperson of the main tribe four years ago. Under a new tribal constitution that makes her chief for life, she has established strict membership criteria based on a baptismal litmus test.

Lopez’s council claims about 600 official members and 400 “unofficial” members who have not yet filled out applications for tribal membership. Zwierlein’s group claims 440 members, with 60 people working on their applications. The two have labeled the opposing council and its members as a “pseudo” or “splinter” group. Both leaders fiercely guard their enrollment lists and all-important genealogical records. They even question each other’s blood connection to the tribe.

“It is evident that leadership disputes exist within the Amah Band,” the BIA’s acting assistant secretary wrote in Sept. 2000 to Zwierlein and Charles Higuera, who preceded Lopez as chair. “Both the governing bodies of the Amah San Juan Band [now the Lopez group] and the San Juan Bautista Band [the Zwierlein group] claim petition No. 120. Under current policy, the Bureau of Indian Affairs takes no position on any internal conflicts within a petitioning group. When the petition is ready for ‘active consideration’ the Assistant Secretary of the BIA will make a decision as to whom the Bureau will deal with as the representative governing body.”

VISIONS FOR SARGENT RANCH

In the same letter, the government said “it will not decide who the leaders of the group are,” but their acknowledgment of a particular council will have long-lasting effects on a tribe with leaders who hold vastly different visions for the land and their people.

“We would like to see the land preserved,” said Lopez. “I’d like to work cooperatively with some of the local environmental groups to ensure that it’s never developed and, at the same time, to allow us to adapt it for ceremonies, prayer, and preservation.”

Zwierlein has pursued a different vision and strategy since forming her own group. She has struck a multi-million dollar land deal with Contra Costa developer Wayne Pierce that lays the groundwork to develop the Sargent Ranch property, located west of U.S. 101 at the southern tip of Santa Clara County just south of Gilroy.

Under an economic development plan Zwierlein submitted to the BIA, Pierce would provide the Amah Mutsun with $21 million for a cultural center and 3,500 acres of the 6,500-acre ranch. Of that, 500 acres would be reserved for tribal members’ homes and businesses, as well as open space and the cultural center. The remaining 3,000 acres would be leased back to Pierce.

Santa Clara County supervisors have rejected Pierce’s efforts to develop Sargent Ranch, rebuffing three attempts in the last 10 years to build golf courses and estate homes on the land. Zwierlein presents a new opportunity. If her group wrests control of the tribe, gains federal recognition, and successfully places Sargent Ranch in trust, Pierce – via his contract with the Indians – will have a chance to sidestep county zoning laws and move forward with development.

In an e-mail response to questions, Pierce said that “the only consideration on the table is senior housing ranging from active adult to congregate care facilities. We will do it in a manner that respects the environment and leaves much of the land pristine, and we will properly consult with local officials as any plans proceed.” He said any discussion of development is “premature,” given the lengthy process of placing land in trust.

Before that, a tribe must gain federal recognition – a complex process that normally takes years. The Amah Mutsun filed their initial petition for acknowledgment as a unified tribe more than 10 years ago, but Lopez’s group lost its momentum for acknowledgment with the departure of Zwierlein, whom he accuses of stealing tribal enrollment lists, genealogies, and other research.

Zwierlein admits to taking the documents but offered no apologies. In fact, she said the thousands of hours she personally put into the research entitled her group to the records.

Lopez claims the documents in Zwierlein’s possession belong to the entire tribe since they were paid for with $195,000 in federal grants. The BIA has cited federal privacy exemptions in refusing to furnish Lopez with copies of the enrollment lists and genealogies. Lopez said he has spent the last four years in a game of catch-up, reconfirming tribal enrollment and retracing genealogies on a shoestring budget. His group currently has $2,000 in the bank and is looking for pro bono legal and genealogical assistance to complete their federal application in hopes of filing for active review within a year.

Meanwhile, Zwierlein’s application has kicked into high gear with the aid of Pierce’s financial backing. The developer has hired public relations firm Edelman and lobbyists Pillsbury Winthrop, both based in Washington, to press members of Congress for legislative recognition of the tribe – a move that could shave a decade off the normal bureaucratic process.

Pierce has also paid for a genealogist and legal historian to meet the BIA’s stringent requirements for recognition.

In October, Zwierlein sent the BIA a final and critical piece in her group’s application for acknowledgment – a legal history that documents the culture of the tribe and ties it to Sargent Ranch.

HISTORY BY HART

“They initially asked me to review the petition for historical accuracy and to see if I thought there were weak points,” said Richard Hart, a legal historian who has specialized in Indian affairs for more than 30 years.

“I thought that they needed more on cultural continuity in the 20th century,” he said. “I did an ethno-historical work, using interviews and field notes of research that was done in the ’20s and ’30s. I was able to show that there is considerable cultural continuity.”

Since starting his research in 2002, Hart has completed three documents, each at least 40 pages in length. He completed the last one in October and has submitted it for publication in a legal magazine. The documents also have been filed with the BIA as part of Zwierlein’s application for federal recognition.

In its Sept. 2000 letter, the agency said it would consider information “submitted by both groups as in support of one petition.”

Hart, who charges $95 per hour for his research, declined to say how much Pierce has paid for his work. He said he has not participated in any lobbying efforts on behalf of the tribe, although he acknowledged sending copies of his research to a caseworker in U.S. Representative Mike Honda’s San Jose office.

It appears efforts to fast-track tribal recognition on Capitol Hill have made little progress since September, when Honda rejected the idea of leading a legislative push. U.S. Representatives Zoe Lofgren and Sam Farr, whose districts border the Sargent Ranch property, have said they would not back a legislative solution at this time.

In the absence of legislative action, the tribe will have to spend years wading through the federal recognition process, according to BIA spokesman Gary Garrison.

“Some people come at it like it’s applying for a license,” he said, “but it’s a long, drawn out, lengthy, in-depth process, because at the end of it, it carries quite large ramifications.”

He explained that the Office of Federal Acknowledgment has three teams – each made up of an anthropologist, genealogist, and historian – who independently confirm all information submitted for each application. Currently, OFA is reviewing six cases, with each team assigned two applications.

Garrison said that “on paper, the time limit [for each case] is two years,” but in practice, applicants or the federal researchers typically request extensions that can delay the process for years.

With six applications under “active review” and 12 groups ahead of the Amah Mutsun on the waiting list, the tribe faces at least another decade before their review even begins.

“The BIA was criticized a couple years ago for the slowness of the process,” Hart said, “and they responded by pointing out that they’re really understaffed. So far, from what I’ve seen, they’ve done a good job with the Mutsun application. But they’re overwhelmed.”

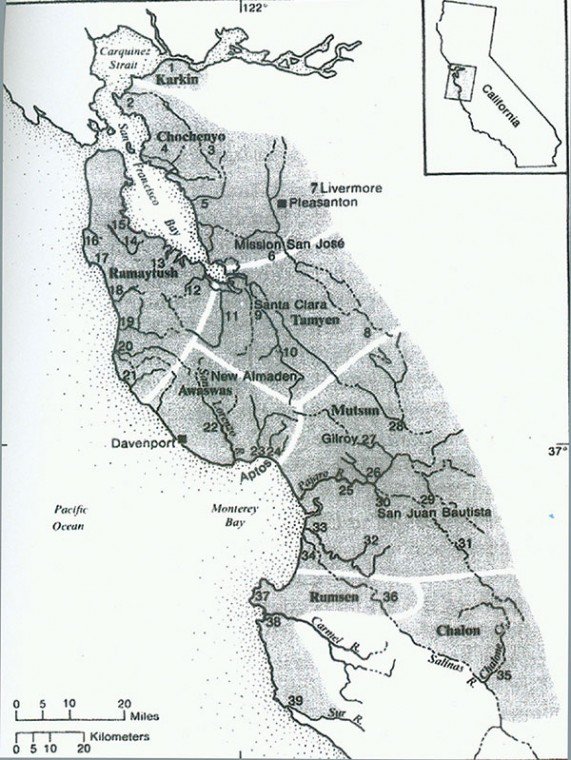

Hart’s legal history emphasizes the connection between the Amah Mutsun tribe and Old Mission San Juan Bautista, where Indians from area villages were forcibly relocated during the Spanish mission period, beginning in the late 1700’s.

When the United States won the Mexican-American War in 1848, the Spanish missions were forced to give up the ranches and “de-missionize.”

“The Indians on the land had been the workforce,” Hart said. “Then the ranches became land grants and the Indians continued to work on them.”

Hart’s research links the Amah Mutsun to the land surrounding the mission, including a village known as Juristac, or present-day Sargent Ranch. He bases those early ties in large part on mission baptismal records, which identify the villages tribal members were taken from. Those records fell into disarray following the end of the mission period, according to Hart, who relied on interviews, field research by linguists, and other historic records to complete his cultural history of the tribe from that date onward.

Zwierlein’s constitution

The new constitution adopted by Zwierlein’s council uses baptismal records as the standard for membership. The tribal constitution states that “each prospective member must be able to trace his or her ancestry to Mission San Juan Bautista via baptism prior to and through 1840.”

A 1990 constitution, approved under Zwierlein’s chairmanship and still in effect under Lopez, contains no such clause restricting membership directly to the San Juan Bautista mission.

The new clause would separate from the tribe numerous people who have been part of the Mutsun community for generations, according to Quirina Luna-Costillas, co-founder and president of the Mutsun Language Foundation. She called Zwierlein’s constitution “hypocritical.”

“A lot of Indians who were, say, from San Juan originally, lived in rancherias in San Juan,” Luna-Costillas explained. “To be taken to a different mission is totally beyond your control. To say you’re a tribal leader and are supposed to do good for your own people, you’re doing them a disservice by saying, ‘Well, you were taken to a certain mission, therefore you don’t qualify. You’re no longer part of us – the Indian community.”

Zwierlein countered that the membership requirement comes in response to government demands.

“The BIA said to ‘pinhole your people,’ ” Zwierlein said, referring to a technical assistance letter she says the agency sent her. “Put your people in one place and work from there. That was a directive out of 1996. I received three technical assistance letters. … but this one particularly said to start pinholing your people.”

Hart’s research emphasizes the importance of ties to the San Juan Bautista Mission, yet he acknowledged that “a tribe is a living thing” and that separations occurred.

“The problem with the [BIA], rightly or wrongly, is that they say blood relation alone is not enough,” he said. “You have to have cultural continuity. You probably had people go to Santa Cruz or Carmel, because those missions were established earlier.”

“I was asked to respond to the criteria that were set up,” Hart said, “and I’m not always sure that it’s fair.”

Hart’s work has allowed Zwierlein to place Petition No. 120 into the cue of groups ready for review. The change in status draws the tribe closer to the day when its identity will be decided.

If Zwierlein and her constitution prevail, that would not only crack open the door to development of Sargent Ranch, but also threaten to cut off many tribal members who cannot meet her strict membership requirements.

Luna-Costillas has devoted her life to piecing together the fragments of her people’s shattered culture. She views with skepticism any narrow definition of her people, who have struggled through centuries of enslavement, brutality and relocation. While acknowledging the importance of some blood connection, she sees culture and community as the true heart of her people.

“I think there is a really big difference between being part of the community and just having blood,” Luna-Costillas said. “One of our [Mutsun Language Foundation] board of directors is Mutsun but he hasn’t quite found his missing link. He knows he’s a San Juan Indian but he hasn’t been able to get that baptism record which is required by the government. For me, his family being part of our community should definitely be enough.”