One of my favorite South Valley places for a daytrip getaway is

the Pinnacles National Monument in southern San Benito County. The

wilderness park turned 100 years old last Wednesday with a

”

rededication ceremony

”

that even Teddy Roosevelt showed up to to help celebrate.

One of my favorite South Valley places for a daytrip getaway is the Pinnacles National Monument in southern San Benito County. The wilderness park turned 100 years old last Wednesday with a “rededication ceremony” that even Teddy Roosevelt showed up to to help celebrate.

You can credit Schuyler Hain for the fact that the former U.S. president made an appearance at the centennial birthday bash. (OK, it was really a Roosevelt replacement standing in.) Without Hain, who has gone down in local legend as “the Father of the Pinnacles,” the South Valley might never have gained this rugged park where visitors can hike through or climb upon mind-blowing rock formations.

I learned about Hain’s colorful history with the Pinnacles during a phone chat with Carl Brenner, chief supervisor of interpretation and education at the national monument. Brenner told me that Hain came out to California from Michigan in 1891 and settled in the Bear Valley region of San Benito County to start a ranch. Soon after his arrival, locals showed him the nearby needle-like rock formations fashioned from volcanic activity and millions of years of erosion. Ranching families had long gone there for picnic outings. For Brenner, the outlandish landscape was a thing of beauty.

He fell in love at first sight.

On Easter Sunday 1893, a respected Stanford University geology professor named Grove Karl Gilbert visited Hain’s ranch. Of course, Hain had to show this famous rock hound the incredible terrain of the Pinnacles. Gilbert was astounded. He had visited South America, Alaska, the Alps and Yosemite Valley to study their unique geology. But those places paled in comparison to what Gilbert beheld at this little known back country haven bordering Monterey and San Benito counties.

Hain originally thought the unusual Pinnacle formations were common in California. But after Gilbert enlightened him to the fact that they were exceptional, the Bear Valley rancher decided to take action to make sure they were never exploited or ruined by commercial operations. He set out to get national legislation passed to preserve the Pinnacles.

As with all such stories, Hain hit major political roadblocks at the beginning of his quest. He was a greenhorn in the Washington game and didn’t at first understand that getting a bill passed for some obscure piece of real estate way out west would be a frustrating enterprise.

A lesser man would have soon given up. Not Hain. He persisted and spread his message by speaking to various groups such as Rotary and Chamber of Commerce members, showing them a magic lantern show of 50 hand-painted project slides of Pinnacles geology and wildlife. He gave tours to interested people and published articles in newspapers and magazines encouraging safeguarding this irreplaceable environment.

Eventually, he gave a tour of his beloved wilderness terrain to U.S. Congressman James Carson Needham of Fresno, who opened some important doors for him. Needham gave Hain’s political campaign some much needed direction that allowed him in 1902 to connect with David Starr Jordan, the president of Stanford at that time.

It took some time to convince Jordan of the importance of the Pinnacles, but when he saw the light, this influential man helped Hain reach Gifford Pinchot, the head of the U.S. Forest Service. With Jordan’s backing, Pinchot in July 1906 proclaimed 16,000 acres of Pinnacles land a National Forest Reserve. It was a bit of a stretch because, other than a few digger pines scattered around the hills, there wasn’t much of a forest there.

In 1907, Congress passed the Antiquities Act. This law allowed the U.S. president to create national monuments to protect American locations of scientific or historic value. Pinchot suggested to President Theodore Roosevelt that the Pinnacles be made one of the first national monuments.

The Rough Rider commander in chief obliged on Jan. 16, 1908 by signing a proclamation perpetually preserving the Pinnacles. Hain’s dream had become a reality.

“Even at that point, Mr. Hain did not sit on his laurels,” Brenner told me. “He continued to support the monument.”

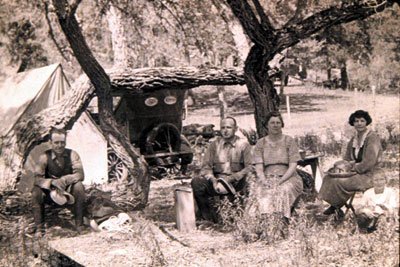

For the next couple of decades, Hain provided tours and lodging to visitors, acting much as an unofficial – and unpaid – monument supervisor. After World War I, Hain tried to turn the 16,000 acres around the Pinnacles rock formations into a place for soldier vets to recuperate in a setting of natural splendor. He suggested calling the land the American Legion National Park. The National Park Service declined pursuing Hain’s proposal.

If you love the great outdoors, I encourage you to visit the Pinnacles and check out for yourself the reason Hain fell it love with this location. If you visit some time during this the park’s centennial year, it would be particularly appropriate to remember the efforts of the tenacious South Valley rancher who protected this natural wonder for everyone’s enjoyment.