Where, oh where, did Casey Tibbs go? A life-size model of the

famed local bronco-rider and his bucking horse

”

War Paint

”

has watched over the intersection of Sixth and Monterey streets

for more than 50 years, perched atop the antique building facing

Old City Hall.

Gilroy – Where, oh where, did Casey Tibbs go?

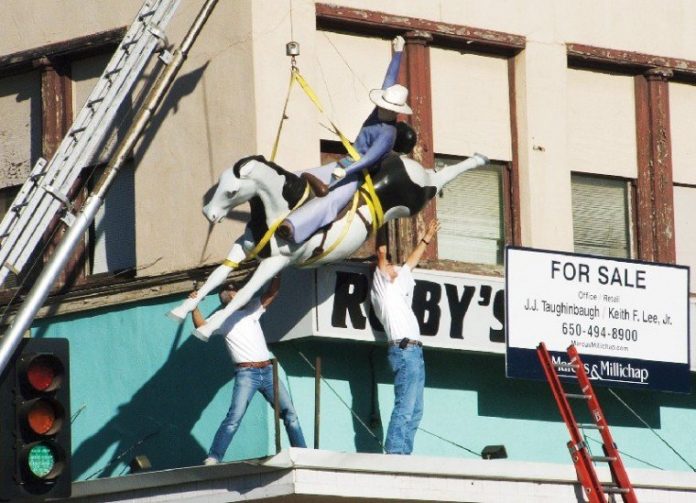

A life-size model of the famed local bronco-rider and his bucking horse “War Paint” has watched over the intersection of Sixth and Monterey streets for more than 50 years, perched atop the antique building facing Old City Hall.

But the familiar pair was gone Tuesday afternoon, and so vanished the last vestige of the Gilroy Gymkhana, a popular annual fiesta from 1929 to 1956 that celebrated the town’s ranching heritage.

“Casey may have gone home to the range,” said Joanne Hall, the wife of George Hall, who is selling the abandoned building at 7401 Monterey St. “Perhaps he’s getting dolled up, but that’s all I’m going to say.”

The couple ran Hall’s Western Wear at the cornerstone until the early 1990s after taking over from George Hall’s father, Bill, who opened the shop in 1931. The Halls’ real estate agent, Keith Lee Jr. with Marcus & Millichap, confirmed that the couple had found a buyer for the property and that money was in an escrow account, “but nothing’s final,” he cautioned.

Neither Lee nor Hall would disclose the name of the buyer.

Known officially as the James Ellis building, it opened in 1872 and is the oldest building on the block. Many worry about the fate of the cowboy icon if the building transfers hands.

“The statue symbolizes the Western era of our history,” said Connie Rogers, chairwoman of the Historical Society. “The building is not the most beautiful building on Monterey Street, but it’s the oldest, and the statue is a symbol of the things that make us what we are today.”

There are many other things that compose Gilroy’s identity, Rogers said.

“We were originally the hay and grain capital around the 1850s, then tobacco in the 1870s, then fruits and nuts, and by the early 1900s, we were the dairy capital,” Rogers said. “After we were the dairy capital, I guess you can say our cowboy period was next, and now we’re the garlic capital.”

Regardless of what comes next, Rogers said she hopes the Halls will preserve Tibbs and his horse for a future use downtown.

Another memory of the gymkhana exists in the artistic frieze above the bar at the Harvest Time Restaurant below the Milias Apartments at the same intersection. The building used to be a hotel where the gymkhana committee would meet and drink.

Indoor mementos aside, Gilroy Museum Coordinator Lucy Folorzano said she didn’t know what the monument’s destination was. Neither did the city’s Public Arts Committee, but last week the body caught wind that the Halls were about to sell their property, so it sent a letter to the couple asking that they not let anything happen to Tibbs and War Paint, according to a city worker with knowledge of the letter.

“The public art committee was concerned about the building for sale and didn’t know what would happen,” said the city staffer, “so it wrote to the Halls, letting them know that it would like to do whatever it could to keep [the statue] downtown.”

A few years ago it was repainted and spruced up in anticipation of a move to Gilroy Gardens, but the statue stayed put.

Tibbs, albeit a South Dakota man, was beloved in these parts during the gymkhana’s heyday after World War II. According to the Casey Tibbs Foundation, in 1949, at age 19, he became the youngest man to win the national saddle bronco-riding crown. And between 1949 and 1955, he won six such championships, which is still a record.

He also was an ambassador for his sport, appearing in movies and television shows and introducing rodeo to Japan. He died in 1990, a few weeks before his 61st birthday. Gilroy Rancher Don Silacci remembers Tibbs “as just an all-around good fellow.”

Carol Peters agreed.

“That thing’s been there since the dawn of man,” said Peters, a painter and retired Gilroy High School art teacher who graduated from GHS in the late ’60s. She said students would steal the monument as a prank during football rivalries.

“I know the Halls collect art. They’re not the type of people that would destroy something like that,” Peters said. “Maybe they’re giving it a new touch-up.”

Maybe, at least that’s Joanne Hall’s story.

Larry Cope is equally optimistic.

“I believe the Halls will keep the monument for long-term posterity,” said Cope, the executive director of Gilroy’s Economic Development Corporation, who added that he knew the Hall’s property was for sale, but didn’t know its future, or the statue’s.

If the monument disappears, though, Gilroy’s history will gain some mystery.

“You know how people go through different phases during their lives?” Roger asked rhetorically. “Well, so do towns, and that was our cowboy phase. It was a big deal at that time.”