Today, The Dispatch begins a weekly question-and-answer feature

on the perchlorate water contamination in South Valley. Please

e-mail your questions to ed****@****ic.com or fax to 842-2206.

We’ll research it and provide the best answer we can find.

Today, The Dispatch begins a weekly question-and-answer feature on the perchlorate water contamination in South Valley. Please e-mail your questions to ed****@****ic.com or fax to 842-2206. We’ll research it and provide the best answer we can find.

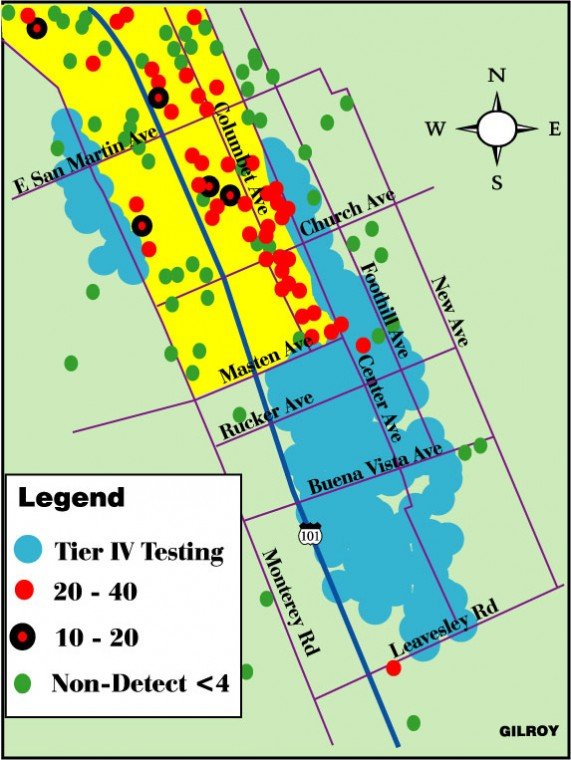

Q: Why didn’t the Regional Water Quality Control Board expect the perchlorate plume to spread so far?

A: The initial contamination site in Morgan Hill had a relatively low concentration of perchlorate when it was tested, leading officials to believe the spill was minor. Officials now believe, based on further well testing, the dangerous chemical likely was spilled years ago over the course of many years when Olin Corp. ran its safety flare manufacturing site from 1955 to 1996.

“It didn’t look like a big spill, so it did delay our appreciation of how big the problem is,” said Thomas Mohr, solvents and toxics cleanup liaison for the Santa Clara Valley Water District.

Q: How long will it take for potassium perchlorate that goes into the underground aquifer today to reach north Gilroy?

A: Water in the main aquifer is flowing in a southeasterly direction from the Tennant and Railroad avenues source, at an estimated rate of 2.5 feet-per-day. Depending on the composition of the surrounding subsurface alluvial soils – and given a geological variable of between 20 and 40 percent, at 2.5 feet-per-day – it is estimated that the water will take 40 years to travel seven miles. It is approximately 7.5 miles between the Olin site and the north Gilroy well on Leavesley where the chemical was found. It has been 48 years since Olin Corp. first began manufacturing highway safety flares using perchlorate on the site.

Q: Is there a way to remove potassium perchlorate from well water?

A: Yes, there are three basic ways, but none of them are cheap or easy.

General remediation – Special filtration systems are placed between the water source and the water user. There are many types of filtration systems, but none are produced specifically for private well users. They cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to construct and operate.

Phytoremediation – Root systems from trees act as filters. This method is still being researched for its effectiveness.

Distillation – Water temperature is elevated past the boiling point to remove perchlorate. Unfortunately, the energy costs involved make it more expensive than any other system.

Q: Will a home distiller work to remove potassium perchlorate?

A: Yes, distillation will work to create clean drinking water of any salt. However, distillation creates residue in which perchlorate is concentrated. The residue is typically drained into the sewer, but in San Martin it is either spilled on the ground or goes into the septic tank system. Although septic tank systems can potentially remove perchlorate – it can be biologically degraded – there is no evidence yet about whether or not it could leach back and pollute groundwater, according to Jim Crowley, senior engineer for the SCVWD.

The processed water sold in bulk by The Water Outlet at West Dunne Avenue and Monterey Road undergoes filtering and distillation.

Q: Why can’t tests measure below 4 parts per billion?

A: Tim Costello, laboratory director, Sequoia Analytical Laboratories in Morgan Hill – “That’s really just the limitations of the instrument. We have an ion chromatograph (system), which as far as I know is a state-of-the-art instrument to test percholorate. The EPA mandates what is called a method detection limit study to see the test limit your instrument is capable of measuring at. Basically if we run a sample and get a percholorate peak of less than 4 ppb, it almost doesn’t even give a response on the chromatograph. Sometimes we can give a rough estimate (below that level), but it’s nothing under our accreditation that we could reliably report. We have to follow our licensing methods and guidance. The EPA writes the methods and sets the general guidelines. The California Department Health Services actually certifies laboratories.”

Q: Why did the state change its “action level” for perchlorate from 18 ppb to 4 ppb?

A: James S. Crowley, an engineer with the Santa Clara Valley Water District’s Groundwater Cleanup Oversight Program Unit – The state Department of Health Services first established an action level of 18 ppb following its perchlorate findings in 1997, when in cooperation with the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment it reviewed 1992 and 1995 evaluations by the federal Environmental Protection Agency. The 18 ppb level corresponded to the upper value of the 4 to 18 ppb range that resulted from the EPA’s provisional reference dose for perchlorate, based on the chemical’s effects on the thyroid gland.

With the 2002 release of EPA’s revised draft reference dose, which corresponded to a perchlorate concentration in drinking water of 1 ppb, DHS concluded that its perchlorate action level needed to be revised downward. In January 2002, it reduced the action level to 4 ppb, the lower value of the range that had resulted from the earlier provisional reference dose and the detection limit for reporting.